War between the Syrian Democratic Forces and Turkey?

This Business Insider article by Fabrice Balanche of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy (WINEP) reflects the potential confrontation by advancing Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), composed of Kurdish PYD, Arab and Assyrian units with Erodgan’s Turkey after seizing the strategic Tishrin Dam and crossing to the West Bank of Euphrates River with the support of U.S. coalition air support.

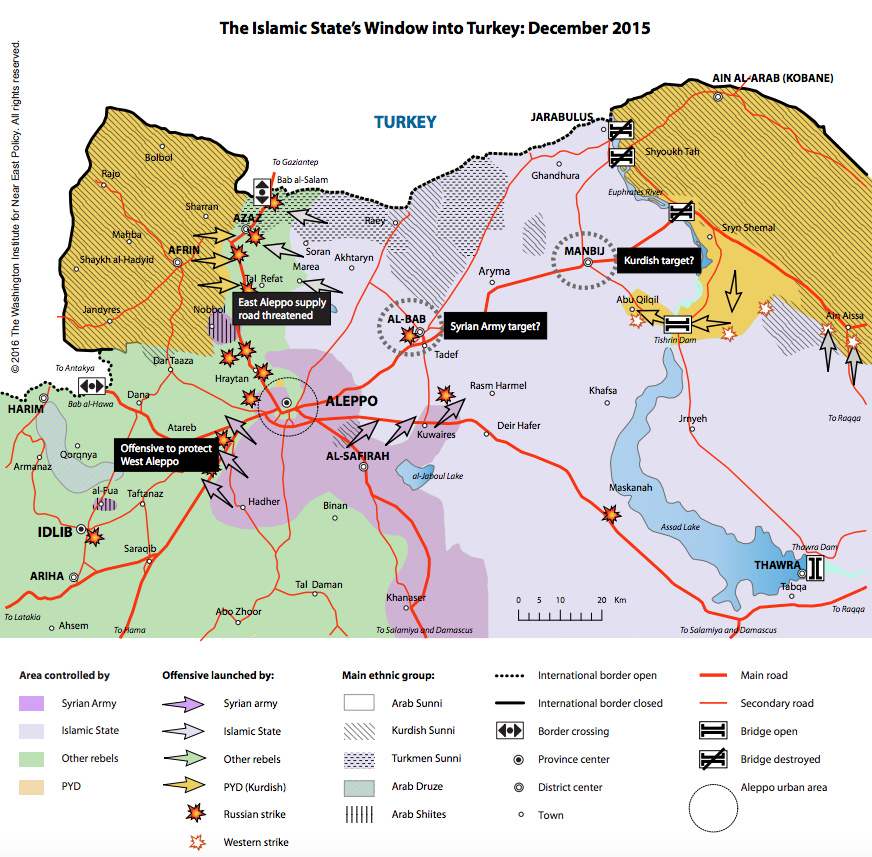

Map Source: Washington Institute for Near East Policy

The border area is a largely rural agricultural area with mixed Arab and Turkmen population. There is evidence that the Arab tribes in the region would pledge support for the PYD led SDF. There is a possible link up between advancing Assad forces with Russian air support and SDF units cutting off IS from the open border to Turkey possibly resulting in isolating the self declared Caliphate of the Islamic State at Raqaa. The Kurds consider this border region as historically Kurdish legacy area. The Russians have already coordinated with the advancing Kurdish YPD led SDF in northern Aleppo province.

The combined Saudi/ Turkish Jaish-al Fatah (JF) rebels are defending a supply road against Kurds to the West and Assad forces to the south. Russian aerial bombardment could result in loss of control and encirclement of the JF rebels. Hence, the likelihood of a dilemma for the U.S. coalition in the war against ISIS with a NATO ally determined to bar any Assad-SDF linkup closing off the current open border with Turkey.

What follows is analysis by Balanche in this Business Insider article drawn from a definitive report published by WINEP, ”The Kurds may be winning against ISIS, but they could end up making tensions in the region worse:”

Although the latest Kurdish offensive runs the risk of spurring direct Turkish intervention, it could also help isolate Islamic State forces in the area from their capital, with significant implications for the rest of the combatants in Syria.

Since October, Islamic State (IS) forces in the eastern part of Syria’s Aleppo province have been under pressure and compelled to fight on several fronts: against the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its Arab allies near the large Tishrin Dam; against the Syrian army and Russian aircraft around Kuwaires military airport and al-Jaboul Lake; against the rebel umbrella group Jaish al-Fatah (dominated by Ahrar al-Sham and al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra) in the Azaz corridor between Aleppo and the Turkish border; and against the local population in Manbij, toward which the PYD and its allies are advancing.

With the PYD seizing the only intact bridge across the Euphrates River for several hundred miles and the Syrian army potentially advancing further north or west, a large group of IS fighters in the Aleppo area could be left without land access to their capital in Raqqa. This prospect raises the question of who would benefit from eliminating IS on this front, and how.

Kurds consider large parts of this area as their own, including the long zone along the Turkish border — not only the Kurdish-held cantons of Afrin to the west and Kobane to the east, but also the sections in between that are currently held by rebel groups or IS. The Kurds have similar views on Manbij, which lies well south of the border. Even if the population in some of these areas is mostly Arab, the PYD still considers them “historically Kurdish,” seemingly basing their argument on notions from the Middle Ages and Salah al-Din.

Accordingly, the PYD aims to ensure territorial continuity between its Afrin canton and the rest of its self-proclaimed Kurdish region (called Rojava). The group has already annexed the predominantly Arab district of Tal Abyad further to the east, but it will be difficult to replicate that feat in more heavily populated districts — as of 2010, more than a million people resided in the contested districts of Azaz, al-Bab, Manbij, and Jarabulus, compared to around 130,000 in Tal Abyad.

Of course, hundreds of thousands of civilians have since fled to Turkey, but the Kurds would still face the challenge of integrating a large Arab population into Rojava — not to mention the local Turkmen minority, which is under Ankara’s protection.

Indeed, Turkey refuses to let the Kurds control the entire border and has warned several times that it will attack them if they cross the Euphrates, as it did in July when it shelled a PYD position near Jarabulus. On December 26, the Democratic Forces of Syria (an umbrella group for the PYD and its Arab allies) seized Tishrin Dam, and then took the village of Abu Qilqil on the other side of the river three days later, bringing them only twelve kilometers from Manbij.

Since the November terrorist attack in Paris, Europeans have insisted that the Islamic State’s two-way route through Turkey be closed for good. In the absence of a moderate Arab Sunni force able to meet this demand, the West would prefer that the corridor be closed by Kurds rather than al-Qaeda-linked groups such as Ahrar al-Sham or Jabhat al-Nusra.

The Kurds are eager to fulfill their dream of a united Rojava along the entire northern border, and to deny them at least some progress toward that goal would be to stop the only effective ally against IS in northern Syria. If the West does not work with them on this objective, it will push them into the arms of Moscow, which has made clear to the PYD that it is quite willing to help; in fact, there is already clear Kurdish coordination with Russian forces in northern Aleppo province.

At the same time, allowing the PYD to seize the entire border is unacceptable to Turkey, and the West needs Ankara’s assistance on several fronts, including the refugee issue and the fight against IS. Therefore, if the PYD offensive continues toward Manbij and perhaps even further beyond Turkey’s Euphrates redline, the United States and its coalition partners will need to be careful in determining whether, where, and how to support the advance — and what to say in response to Turkish protests.

For its part, Ankara will need to decide how far it is willing to go in enforcing that redline given the political and diplomatic risks of deeper intervention, especially against the only ground force making progress against IS in Syria. In that sense, the PYD’s offensive is as clear a signal as Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon: the die is cast.

EDITORS NOTE: This column originally appeared in the New English Review.

What Syria needs, most of all, is an end to this war.

As IS, JAN, Al Sham and other islamist jihadis will never stop, they must be defeated.

To defeat them, the border must be closed and Turkey will not do that.

SDF taking the Azaz Yarablus corridor, or at least closing it, would cut of arms etc for all rebels in the north.

It would also prevent refugees going north.

At that point, negotiations might become possible