Yes, it is a Virtue to Reject Charity by Jeffrey A. Tucker

There is a moment I found a bit startling in the new Anne of Green Gables series on Netflix. The farm is in trouble and the bank is talking foreclosure. The family starts to panic. Anne suggests that many people will chip in and help the family through these hard times.

The mother reacts with firmness and conviction: “Absolutely not. We do not accept charity.”How old fashioned! The statement alone reveals we are talking about the past here. I vaguely recall people in my own extended family – at family reunions in West Texas, sitting around shelling peas – saying something similar. It was a matter of pride, even morality.

When was the last time you have heard that assertion? I personally can’t remember hearing that in many years.

Maybe it is time to bring back that ethos and ethic.

What we have here is a principle at work, a matter of character. Don’t live at other’s expense. Make your own way in this world. Keep your independence and retain your dignity.

Is there any virtue here? I would suggest so. It is a forgotten virtue, to be sure, but a virtue nonetheless.

Charity with Dignity

The family in the story truly needed help. Rather than beg, they gathered up many of their possessions and took them to town to sell them. Merchants had heard about the family’s need, so some actually overpaid as a way of helping without letting the family know what was going on.

This is a great way to be charitable without letting the person know about it, which is yet another expression of virtue. The Bible tells people to give unto others without letting the left hand know what the right hand is doing – which is to say, don’t congratulate yourself and likewise expect others to praise you for your generosity. This is what the neighbors did.

By the same token, the shame associated with begging is ever-present in the Bible. In the parable of the unrighteous steward, the guy complains that he is been released from his master, but he is too weak to dig and “too ashamed to beg.”

Ashamed! Can you imagine? Social welfare professionals have been trying to remove the stigma of welfare for a century. But let’s face: it will never entirely go away. That might even be a good thing.

Don’t Be a Beggar

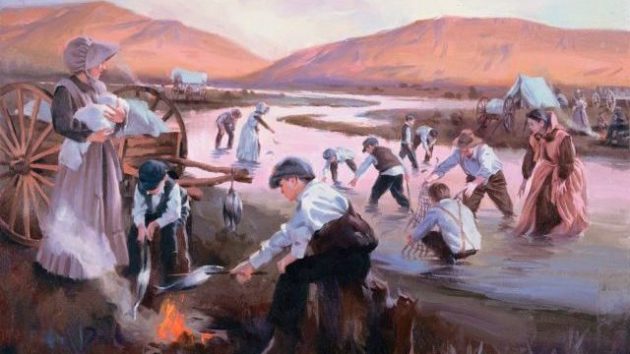

The story of Anne is set in Canada, but the attitude behind it feels quintessentially American. It is fundamentally a character trait forged in a setting of freedom. You encounter this often in the Little House books too, this attitude that it represents something of a humiliation to accept charity from others.

Even when the opportunity is there, there once seemed to be a cultural commitment against dependency, against living off others. Think of the old term hobo. The hobo ethic was never to beg – that’s what bums do – but rather to completely avoid all forms of dependency, even the need for a comfortable bed and nice clothes, and to travel and work small jobs to get enough to live and then move on. The hobos believed that this was the only way to stay free.In the American spirit, the hobo was making a dignified choice. The bum? Never.

Even when the redistributionist state came along, the American spirit of individualism rebelled.

Rose Wilder Lane, the daughter of the author of those books, writing at the height of the New Deal, put it like this:

The spirit of individualism is still here. The number of us who have been out of work and facing actual hunger is not known; the largest estimate has been twelve million. Of this number, barely a third appeared on the reported relief rolls. Somewhere those millions in need of help, who were not helped, are still fighting through this depression on their own. Millions of farmers are still lords on their own land; they are not receiving checks from the public funds to which they contribute their increasing taxes.

Millions of men and women have quietly been paying debts from which they asked no release; millions have cut expenses to the barest necessities, spending every dime in fear that soon they will have nothing, and somehow being cheerful in the daytime and finding God knows what strength or weakness in themselves during the black nights.

Americans are still paying the price of individual liberty, which is individual responsibility and insecurity.

This view is of course routinely lampooned in the progressive press, overtly by socialists like Elizabeth Warren but implicitly in venues like the New York Times and National Public Radio. Their voices drip with disdain for what they say is the myth of “rugged individualism,” a phrase popularized at the end of the 19th century. It is the supposedly cruel and unrealistic idea that people should get by on their own wherewithal.

The idea behind this phrase is to celebrate individual achievement and to suggest that it is a compromise of your potential as a human being to expect others to care for you if it is not necessary.Too often the idea has been caricatured, at least since the New Deal sought to break down the social stigma of dependency on government. For example, maybe people associate this with selfishness. It’s not true. There is a paradox that the more independent you are, the more you are willing to step up and help others. As Lane says: “We are the kindest people on earth; kind every day to one another and sympathetically responsive to every rumor of distress. It is only in America that a passing car will stop to lend a stranded stranger a tire-tool.”

This is not living off others. This is benefitting from the kindness of others when it is necessary and helpful. You accept it because you would certainly do the same for them. And you don’t expect it from others. And you certainly don’t craft your life around the idea that everyone or anyone is morally obligated to help you when you encounter misfortune.

Help Yes, Dependency No

It’s not complicated: you accept help when necessary but don’t make a habit of it. My own mother, who comes from the stock and heritage that celebrated self-reliance, used to say to me, very simply: “never be beholden.” If you owe others, you have given up that most precious thing, your independence, which means giving up some of your freedom.

That includes owing debt. CNN reports: “Total household debt climbed to $12.58 trillion at the end of 2016, an increase of $266 billion from the third quarter, according to a report from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.” Meanwhile, 44% of Americans don’t have $400 cash that they can throw at an emergency expense.

Private creditors are bad enough. It is surely worse to be beholden to government. Right now 43 million Americans are on food stamps. That is not a mark of national pride. And this is true even in times when groceries are absurdly cheap and available by any historical standard.

Once you accept the largesse, you have a political investment in continuing it. Your loyalties gradually change.

People justify this based on observing how much they are paying into the system. It pillages them with every paycheck, so they might as well get something back. No matter how much welfare they pay in, they can never take enough out to make the bargain work out equally. For most people, this is surely true.Once you accept the largesse, you have a political investment in continuing it. Your loyalties gradually change. The state becomes your benefactor. Your sense of self reliance is compromised.

Do you see the vicious cycle? You are forced to pay in, so you have no moral resistance about taking out when the time arises. Pretty soon you find yourself part of the Bastiatian calculus: the state becomes the great fiction by which everyone tries to live at everyone else’s expense.

In service of people’s dignity, programs like food stamps ought to be abolished, as much as that would upset the corporate agricultural interests that are forever lobbying for this racket to continue.

It seems that government does everything possible to rope people into the role of dependent these days. Whether it is student loans, Obamacare, or just guilt tripping us all to love the highways and glorious national defense we get for our tax dollars, we are supposed to feel forever on the hook, forever beholden. Forever indentured.

This is not the attitude of a free people.

A Word for Individualism

To hear about “rugged individualism” is a bit strange for us today. We have a vague sense that people used to believe this. We feel mischievous even to sense that there might be a grain of truth in it. The attitude built the world’s most prosperous economy. It gave us new inventions. It created the most dynamic, thriving, progressing society in history, and this became a model for the world.

To be sure, there is often a confusion over the phrase self-reliance. It does not mean to grow your own food, make your own furniture, and walk instead of drive. It has nothing to do with the technology you use, and there is a sense in which the market and the division of labor it creates makes us all deeply dependent on each other. That is a beautiful thing.

The point is that market dependency is rooted in exchange and mutual benefit. We go into every exchange with the freedom to change our minds, and we benefit from exchange as much as the other party. We aren’t doing favors for each other. We cooperate together in our own interest.Self-reliance really means something else. It means not being on the hook for a favor someone else did you or being expected to live in a constant state of owing others for some act of benevolence on their part. It certainly rejects forcing others through the state to be productive so that you can get a free ride.

Pay Your Debts

My mother is right. It’s not good to be beholden to others. This idea was once baked into our institutions. Government had no charity to offer anyone. Your debts had to be paid. Americans didn’t rush to create the cradle-to-grave welfare state. The thing existed in Europe long before it came to our shores. Even when we created the institutions, people were reluctant to use them.

And it’s not just about the compromise of your individualism that you make when you accept welfare. It is also about the annoyance others feel when forced to pay for it. Both sides are degraded in this forced wealth transfer.

For our ancestors, it was a matter of personal character.

This is the underlying thinking behind the quote that Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged worked to forge into a life doctrine: “I swear, by my life and my love of it, that I will never live for the sake of another man, nor ask another man to live for mine.”It’s best to think of that line, not as a hard religious doctrine but just very solid life advice, a good bedrock practice for how to think of yourself in relation to others. With that idea in place, all the rest of the virtues fall into place.

What Can We Do About It

The idea of rejecting charity means that you should take charge of your own life, regardless of pressures around you to do otherwise. This is possible even today. It’s true that you are forced to pay into the system. But no one is forcing anyone to take food stamps, to live on handouts, to be dependent on government programs. It’s not so easy to refuse them anymore. The struggle is real. Still, this is something you can control – unlike national politics.For our ancestors, it was a matter of personal character. It is always easier to take the more temporarily lucrative path and the safer route. Maybe you feel like a chump for turning down government money when it is so easily available. But if you relent, what are you giving up in the exchange?

We don’t need to bring back the shame that comes with living off others. Anyone who does that when it is not absolutely necessary knows in his or her heart that there is a better way. If we can choose the better path, we should.

If everyone did this, the welfare state would be de facto abolished overnight.

Jeffrey A. Tucker

Jeffrey Tucker is Director of Content for the Foundation for Economic Education. He is also Chief Liberty Officer and founder of Liberty.me, Distinguished Honorary Member of Mises Brazil, research fellow at the Acton Institute, policy adviser of the Heartland Institute, founder of the CryptoCurrency Conference, member of the editorial board of the Molinari Review, an advisor to the blockchain application builder Factom, and author of five books. He has written 150 introductions to books and many thousands of articles appearing in the scholarly and popular press.

Jeffrey Tucker is Director of Content for the Foundation for Economic Education. He is also Chief Liberty Officer and founder of Liberty.me, Distinguished Honorary Member of Mises Brazil, research fellow at the Acton Institute, policy adviser of the Heartland Institute, founder of the CryptoCurrency Conference, member of the editorial board of the Molinari Review, an advisor to the blockchain application builder Factom, and author of five books. He has written 150 introductions to books and many thousands of articles appearing in the scholarly and popular press.

EDITORS NOTE: Get trained for success by leading entrepreneurs. Learn more at FEEcon.org

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!