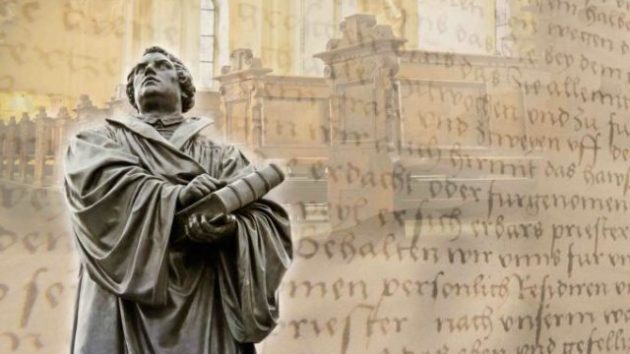

Haunted Luther: October 31st, 2017 the 500th Anniversary of the Protestant Reformation

Brad Miner reviews four new books about the Protestant Reformation on the eve of the 500th anniversary of Luther’s rebellion.

The choir was still singing “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God,” when I said to the celebrant, “Why do we sing a hymn by the heretic Luther?”

The priest was speechless until I said I was joking – sort of.

Any Catholic may be forgiven for not objecting to the hymn, since Pope Francis surely doesn’t. In his speech at a Catholic-Lutheran gathering in Sweden he said of Luther:

[he] challenges us to remember that apart from God we can do nothing. “How can I get a propitious God?” This is the question that haunted Luther. . . .The doctrine of justification thus expresses the essence of human existence before God.

The Holy Father may not here have said that the very doctrines advanced by Luther and led to the splintering of Christian unity in the West are now mooted, but one understands why his words were the occasion of some confusion.

Tomorrow marks the half-millennium anniversary of the day Luther may (or may not) have tacked his protests to the door of All Saints’ in Wittenberg, and clarity about what the reformer was up to (and what it has led to) may be perused in four new books:

Heroes & Heretics of the Reformation by Phillip Campbell

The Reformation 500 Years Later: 12 Things You Need to Know by Benjamin Wiker

Grace & Justification: An Evangelical’s Guide to Catholic Beliefs by Stephen Wood

Reformation Myths: Five Centuries of Misconceptions and (Some) Misfortunes by Rodney Stark

In Heroes & Heretics, Mr. Campbell employs a dramatic approach to the story, focusing on the lives of several-dozen figures who embraced either the reform/revolt of Luther or what became the Catholic Counter-Reformation. One senses how disorienting the sixteenth century must have been for Protestants and Catholics alike, although for the latter it was certainly more dangerous. Consider: from 1525 to 1528 England was officially Catholic, Protestant, Catholic again, and then Protestant again. And it says a lot that, to this day, Catholics are barred from England’s throne.

Mr. Campbell’s book is one best appreciated by young readers.

Mr. Wiker’s book deals with the implications of the Reformation – as it happened and since, and, coming from Regnery Publishing, it might easily have joined the popular Politically Incorrect Guide series. It’s written in the same lively style and with the same intent to provoke. Thus: “The first thing to understand about the Reformation is that after five hundred years it is coming to an end.”

Are many Protestants coming to accept aspects of Catholic doctrine, since many Catholic abuses against which Luther protested have long ago disappeared? Are “many” Protestants are actually unhappy about the splintering of Christian unity? I see little evidence of it, beyond a trickle of catechumens every Easter Vigil.

As to Mr. Wiker’s assertions that atheism, paganism, and Islam played major roles in causing the Reformation, I’m mildly skeptical. A revival of interest in pagan writers was certainly a current in the Renaissance; and Luther himself was much impressed with the labors of Desiderius Erasmus, a celebrated Catholic humanist. But he was not a decisive influence on Protestant reformers.

And what Mr. Wiker refers to as an “apocalyptic dread of Islam,” although certainly in the air in Europe well into the 17th century, it seems marginal to Luther’s protest.

Mr. Wood’s Grace & Justification is primer – for Protestants curious about Catholicism but also for ill-informed Catholics – on a key point of Luther’s contention: that the Catholic Church denies salvation comes from the grace of God. Mr. Wood, a Catholic convert, writes: “If anyone claims that the Catholic Church denies that salvation is from the grace of God, he doesn’t know what he’s talking about.” And that’s been true since the year 418.

Mr. Wood is judicious in not wishing, unlike Mr. Wiker, to stir up controversy where none is necessary. But on the subject of justification by faith a chasm appears. Towards the end of the book a chapter asks: “Can I Lose My Justification?” Good question, because most Protestants will answer emphatically, “No!” Wood gets to the heart of the matter, referring to the you-can’t-lose-it-once-you’ve-got-it interpretation:

It misconstrues St. Paul’s teaching to assert that justification by faith is a once-for-all ticket allowing a person to live in serious, unrepentant sin without consequences.

That will lose many Evangelicals and fundamentalists. And Mr. Wood never even addresses the Catholic Bible, Mary, the papacy, relics, etc.

Rodney Stark, who is not Catholic, is a marvelous writer – arguably America’s best writer on the sociology and history of religion. (I reviewed his book on the Crusades here.) His Reformation Myths is a cold shower for those quick to praise Luther’s innovations, which – as Stark explains – mostly failed.

In the nations of Europe that remained Catholic, an uneasy subordination of Church to State was ongoing. Among Catholic and Protestant kings and queens, religion increasingly became important as a source of wealth for the crown. Henry VIII of England, that great opportunist, accumulated what in modern value equals £87 billion from the confiscation of Catholic properties.

But the old, Catholic way had at least the semblance of the God-and-Caesar divide that kept political power in moral check. Protestantism diminished that, as it did religious tolerance, until well into the 19th century. Indeed, European anti-Semitism largely arose from the Reformation – from Luther most of all. Stark quotes historian Diarmaid MacCulloch: “Luther’s writing of 1543 [On the Jews and Their Lies] is a blueprint for the Nazis’ Kristallnacht of 1938.”

The Germans get hard treatment in Stark’s book, not least Max Weber, whose The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism Stark judges to be nonsense – and he cites plenty of data to prove it.

But equally baloney is the claim that splintering Protestantism gave rise to individualism and, then, secularism. I was amazed to read how irreligious religious people were in the Middle Ages.

If you choose one Reformation book to read, let it be Stark’s entertaining and enlightening one.

![]()

Brad Miner

Brad Miner is senior editor of The Catholic Thing, senior fellow of the Faith & Reason Institute, and a board member of Aid to the Church In Need USA. He is a former Literary Editor of National Review. His new book, Sons of St. Patrick, written with George J. Marlin, is now on sale. The Compleat Gentleman, is available on audio and as an iPhone app.

RELATED ARTICLE: The Benedict Option: Relative versus Revelatory Truth

EDITORS NOTE: This column originally appeared in The Catholic Thing. The featured image is of a statue of Martin Luther (CC0 Public Domain/Andibreit).

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!