Excellent Black American Role Models Are Being Erased From History

There is a tragedy of historical and philosophical ignorance that is benefitting a tiny handful of people at the expense and well-being of the vast majority of black Americans.

This tragedy is the ongoing, purposeful scrubbing from the education system the history of successful, self-reliant black Americans before the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s, and the reason for their success and that of large numbers of other blacks.

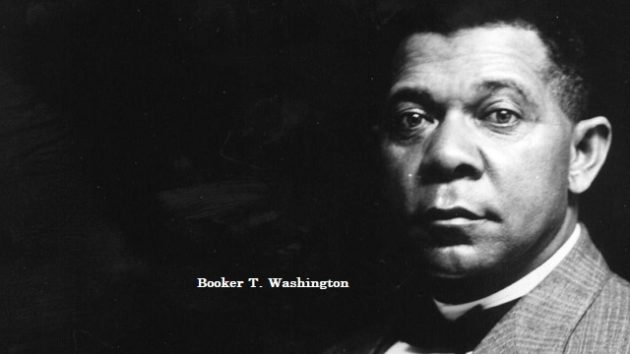

The leading black American at the turn of the 20th century was Booker T. Washington, whose approach was the virtual opposite of today’s grievance-focused approach that looks to government for personal progress. Washington, born into slavery, thought the black man’s best hope lay in personal responsibility, education, entrepreneurship, business and family. And indeed, there were great economic gains arising from that until the 1970s.

The result of this erasure of Washington and others (such as Frederick Douglass) is that black Americans have ever more intently looked to government, ironically still run largely by the dominant race of white Americans, for their future success. This means too many black Americans’ reliance ultimately rests on the largesse of white people, the total opposite of what was being promoted successfully for 60 years after the Civil War.

The Civil Rights Movement was an imperative for black Americans and the strength of all of America, crushing the last poisons of fully institutionalized racism (at least until hiring quotas, affirmative action and intersectionality began reintroducing the poison.) But if it had been married to the earlier teachings of Washington the result almost assuredly would have been a dynamic, black community in full competition with white and Asian Americans.

Washington was born into slavery in 1856, but grew from emancipation to be an American educator, author, orator, advisor to multiple presidents of the United States and for a quarter century until his death in 1915 was the dominant leader in the American black community.

He was a forceful proponent of black-owned businesses and a founder of the National Negro Business League. Based at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama as lynchings in the South peaked in 1895, Washington delivered his “Atlanta compromise” speech. He called for black progress through education and entrepreneurship, rather than trying to challenge directly the Jim Crow segregation and the disenfranchisement of black voters in the South. (Although he quietly helped those who were fighting the Jim Crow laws.) He felt blacks best situation would be had by being self-reliant.

Washington mobilized and led a broad, nationwide coalition of the growing middle-class of blacks, church leaders who were not so much political as Christian, and white philanthropists and politicians who supported his vision. His goal was the long-term, foundational building of the black community’s economic strength and pride through self-help and schooling. In this way, black Americans would not be reliant on the government or the largesse of white people. And their economic strength would naturally integrate them into the American capitalistic culture.

This was precisely what was happening and can be seen in the economic growth among black Americans that erupted in the immediate aftermath of civil rights laws dismantling legal discrimination. This short era was while the concept of self-help was still dominant — before the welfare culture took hold.

According to an in-depth study by the University of Indiana:

“For both African–American men and women, the greatest improvement in labour income relative to their White counterparts occurred in the 1960s and 1970s (Donohue 2007, pp. 1424–25). In the 1960s, African-American men and women of all age groups enjoyed positive growth relative to their White counterparts, with the men enjoying growth rates ranging from 6.5 percent to 21.8 percent, and the women enjoying growth rates ranging from 23.5 percent to 38.7 percent.”

These high growth numbers are actually above the rate of income growth for whites during the same period, meaning that the gap was being closed. Black Americans made their biggest strides in closing the economic gap with white Americans at a time when the self-reliant ethos of Booker T. Washington and others was still somewhat intact, and discrimination laws had been eliminated.

Unfortunately, going forward, the black labor participation rate that was 90 percent in 1970, plummeted to 77 percent by 2010. The white rate went from 95 percent to 91 percent in the same time period. Of course, this was the same time period in which the Great Society took hold.

There are many other data points showing that blacks were closing the gap on whites at a quick pace economically until the welfare state took hold most deeply among black Americans. Then progress not just slowed, but stopped and in some ways went backward. We see more black people in public, successful positions now but that is because of both opportunities and certain advantages that have been created for black Americans tend to accrue to those that already “have,” compared to those who “have not.”

Classic result of state-driven social policies.

Washington understood much of what was happening in his time and what could happen if black Americans took the path that was ultimately taken. His words both lift and inspire — not just black Americans, but all Americans — just as Martin Luther King’s do.

Here are some of his fascinating and worthy insights. (Language is time-stamped. If you are offended, avoid all history and pretend it didn’t exist. But you probably have not read this far if you are of that nature.) You see how Washington consistently looks at the individual, at the character of the man as MLK pointed to, not any outside forces. He is actually far more in the traditional American mode than any of today’s progressives of any race.

“I have learned that success is to be measured not so much by the position that one has reached in life as by the obstacles which he has overcome while trying to succeed.”

“Character, not circumstances, makes the man.”

“Of all forms of slavery there is none that is so harmful and degrading as that form of slavery which tempts one human being to hate another by reason of his race or color. One man cannot hold another man down in the ditch without remaining down in the ditch with him.”

“There are two ways of exerting one’s strength: one is pushing down, the other is pulling up.”

“Men may make laws to hinder and fetter the ballot, but men cannot make laws that will bind or retard the growth of manhood. We went into slavery a piece of property; we came out American citizens. We went into slavery pagans; we came out Christians. We went into slavery without a language; we came out speaking the proud Anglo-Saxon tongue. We went into slavery with slave chains clanking about our wrists; we came out with the American ballot in our hands.”

And these two, that could with little imagination, attach to some current so-called “civil rights” leaders afflicting the county and American blacks:

“There is another class of coloured people who make a business of keeping the troubles, the wrongs, and the hardships of the Negro race before the public. Having learned that they are able to make a living out of their troubles, they have grown into the settled habit of advertising their wrongs — partly because they want sympathy and partly because it pays. Some of these people do not want the Negro to lose his grievances, because they do not want to lose their jobs.”

“I am afraid that there is a certain class of race-problem solvers who don’t want the patient to get well, because as long as the disease holds out they have not only an easy means of making a living, but also an easy medium through which to make themselves prominent before the public.”

It’s truly a tragedy that Washington’s legacy has been erased, that so few students learn of him today, and that we have turned our back on the wisdom of his life and insights.

RELATED ARTICLE: W.E.B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington and the Origins of the Civil Rights Movement

EDITORS NOTE: This column originally appeared in The Revolutionary Act. Please visit the Revolutionary Act YouTube Channel. Help Us Fight For American Values.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!