Starbucks and The ‘Social Responsibility’ of Business to Increase its Profits

There has been controversy surrounding the decision by Starbucks to require its employees (baristas) to discuss race relations with customers when they purchase their lattes. What is the role of a corporation when it comes to social issues? Some corporations use their power to push social issues but at what cost? Is this a hidden tax passed on to customers in the name a a false promotion of social justice? Are corporations using social justice issues to increase their profits by attracting a certain type of customer (e.g. millennials)?

There has been controversy surrounding the decision by Starbucks to require its employees (baristas) to discuss race relations with customers when they purchase their lattes. What is the role of a corporation when it comes to social issues? Some corporations use their power to push social issues but at what cost? Is this a hidden tax passed on to customers in the name a a false promotion of social justice? Are corporations using social justice issues to increase their profits by attracting a certain type of customer (e.g. millennials)?

Is Starbucks, “ In fact they are–or would be if they or anyone else took them seriously–preaching pure and unadulterated socialism.”

Any conversation about any social topic must include all points of view. Are the baristas at Starbucks prepared for a very long conversation?

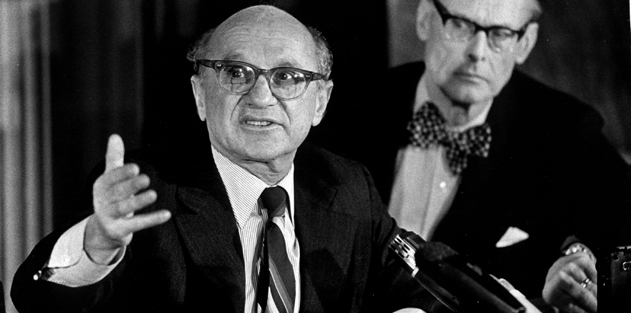

Perhaps Howard Schultz, CEO of Starbucks and other CEOs, should read “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits” written by Nobel Prize Laureate Milton Friedman in The New York Times Magazine on September 13, 1970:

The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits

When I hear businessmen speak eloquently about the “social responsibilities of business in a free-enterprise system,” I am reminded of the wonderful line about the Frenchman who discovered at the age of 70 that he had been speaking prose all his life. The businessmen believe that they are defending free enterprise when they declaim that business is not concerned “merely” with profit but also with promoting desirable “social” ends; that business has a “social conscience” and takes seriously its responsibilities for providing employment, eliminating discrimination, avoiding pollution and whatever else may be the catchwords of the contemporary crop of reformers. In fact they are–or would be if they or anyone else took them seriously–preaching pure and unadulterated socialism. Businessmen who talk this way are unwitting puppets of the intellectual forces that have been undermining the basis of a free society these past decades.

The discussions of the “social responsibilities of business” are notable for their analytical looseness and lack of rigor. What does it mean to say that “business” has responsibilities? Only people have responsibilities. A corporation is an artificial person and in this sense may have artificial responsibilities, but “business” as a whole cannot be said to have responsibilities, even in this vague sense. The first step toward clarity in examining the doctrine of the social responsibility of business is to ask precisely what it implies for whom. Presumably, the individuals who are to be responsible are businessmen, which means individual proprietors or corporate executives. Most of the discussion of social responsibility is directed at corporations, so in what follows I shall mostly neglect the individual proprietors and speak of corporate executives.

In a free-enterprise, private-property system, a corporate executive is an employee of the owners of the business. He has direct responsibility to his employers. That responsibility is to conduct the business in accordance with their desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible while conforming to their basic rules of the society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom. Of course, in some cases his employers may have a different objective. A group of persons might establish a corporation for an eleemosynary purpose–for example, a hospital or a school. The manager of such a corporation will not have money profit as his objectives but the rendering of certain services. In either case, the key point is that, in his capacity as a corporate executive, the manager is the agent of the individuals who own the corporation or establish the eleemosynary institution, and his primary responsibility is to them. Needless to say, this does not mean that it is easy to judge how well he is performing his task. But at least the criterion of performance is straight-forward, and the persons among whom a voluntary contractual arrangement exists are clearly defined.

Of course, the corporate executive is also a person in his own right. As a person, he may have many other responsibilities that he recognizes or assumes voluntarily–to his family, his conscience, his feelings of charity, his church, his clubs, his city, his country. He may feel impelled by these responsibilities to devote part of his income to causes he regards as worthy, to refuse to work for particular corporations, even to leave his job, for example, to join his country’s armed forces. If we wish, we may refer to some of these responsibilities as “social responsibilities.” But in these respects he is acting as a principal, not an agent; he is spending his own money or time or energy, not the money of his employers or the time or energy he has contracted to devote to their purposes. If these are “social responsibilities,” they are the social responsibilities of individuals, not business.

What does it mean to say that the corporate executive has a “social responsibility” in his capacity as businessman?

If this statement is not pure rhetoric, it must mean that he is to act in some way that is not in the interest of his employers. For example, that he is to refrain from increasing the price of the product in order to contribute to the social objective of preventing inflation, even though a price increase would be in the best interests of the corporation. Or that he is to make expenditures on reducing pollution beyond the amount that is in the best interests of the corporation or that is required by law in order to contribute to the social objective of improving the environment. Or that, at the expense of corporate profits, he is to hire “hardcore” unemployed instead of better qualified available workmen to contribute to the social objective of reducing poverty.

In each of these cases, the corporate executive would be spending someone else’s money for a general social interest. Insofar as his actions in accord with his “social responsibility” reduce returns to stockholders, he is spending their money. Insofar as his actions raise the price to customers, he is spending the customers’ money. Insofar as his actions lower the wages of some employees, he is spending their money.

The stockholders or the customers or the employees could separately spend their own money on the particular action if they wished to do so. The executive is exercising a distinct “social responsibility,” rather than serving as an agent of the stockholders or the customers or the employees, only if he spends the money in a different way than they would have spent it. But if he does this, he is in effect imposing taxes, on the one hand, and deciding how the tax proceeds shall be spent, on the other.

This process raises political questions on two levels: principle and consequences.

On the level of political principle, the imposition of taxes and the expenditure of tax proceeds are governmental functions. We have established elaborate constitutional, parliamentary and judicial provisions to control these functions, to assure that taxes are imposed so far as possible in accordance with the preferences and desires of the public–after all, “taxation without representation” was one of the battle cries of the American Revolution. We have a system of checks and balances to separate the legislative function of imposing taxes and enacting expenditures from the executive function of collecting taxes and administering expenditure programs and from the judicial function of mediating disputes and interpreting the law.

Here the businessman–self-selected or appointed directly or indirectly by stockholders–is to be simultaneously legislator, executive and jurist. He is to decide whom to tax by how much and for what purpose, and he is to spend the proceeds–all this guided only by general exhortations from on high to restrain inflation, improve the environment, fight poverty and so on and on.

The whole justification for permitting the corporate executive to be selected by the stockholders is that the executive is an agent serving the interests of his principal. This justification disappears when the corporate executive imposes taxes and spends the proceeds for “social” purposes. He becomes in effect a public employee, a civil servant, even though he remains in name an employee of a private enterprise. On grounds of political principle, it is intolerable that such civil servants–insofar as their actions in the name of social responsibility are real and not just window-dressing–should be selected as they are now. If they are to be civil servants, then they must be elected through a political process. If they are to impose taxes and make expenditures to foster “social” objectives, then political machinery must be set up to make the assessment of taxes and to determine through a political process the objectives to be served.

This is the basic reason why the doctrine of “social responsibility” involves the acceptance of the socialist view that political mechanisms, not market mechanisms, are the appropriate way to determine the allocation of scarce resources to alternative uses.

On the grounds of consequences, can the corporate executive in fact discharge his alleged “social responsibilities”? On the one hand, suppose he could get away with spending the stockholders’ or customers’ or employees’ money. How is he to know how to spend it? He is told that he must contribute to fighting inflation. How is he to know what action of his will contribute to that end? He is presumably an expert in running his company–in producing a product or selling it or financing it. But nothing about his selection makes him an expert on inflation. Will his holding down the price of his product reduce inflationary pressure? Or, by leaving more spending power in the hands of his customers, simply divert it elsewhere? Or, by forcing him to produce less because of the lower price, will it simply contribute to shortages? Even if he could answer these questions, how much cost is he justified in imposing on his stockholders, customers and employees for this social purpose? What is his appropriate share and what is the appropriate share of others?

And, whether he wants to or not, can he get away with spending his stockholders’, customers’ or employees money? Will not the stockholders fire him? (Either the present ones or those who take over when his actions in the name of social responsibility have reduced the corporation’s profits and the price of its stock.) His customers and his employees can desert 3

him for other producers and employers less scrupulous in exercising their social responsibilities.

This facet of “social responsibility” doctrine is brought into sharp relief when the doctrine is used to justify wage restraint by trade unions. The conflict of interest is naked and clear when union officials are asked to subordinate the interest of their members to some more general purpose. If the union officials try to enforce wage restraint, the consequence is likely to be wildcat strikes, rank-and-file revolts and the emergence of strong competitors for their jobs. We thus have the ironic phenomenon that union leaders–at least in the U.S.–have objected to Government interference with the market far more consistently and courageously than have business leaders.

The difficulty of exercising “social responsibility” illustrates, of course, the great virtue of private competitive enterprise–it forces people to be responsible for their own actions and makes it difficult for them to “exploit” other people for either selfish or unselfish purposes. They can do good–but only at their own expense.

Many a reader who has followed the argument this far may be tempted to remonstrate that it is all well and good to speak of Government’s having the responsibility to impose taxes and determine expenditures for such “social” purposes as controlling pollution or training the hard-core unemployed, but that the problems are too urgent to wait on the slow course of political processes, that the exercise of social responsibility by businessmen is a quicker and surer way to solve pressing current problems.

Aside from the question of fact–I share Adam Smith’s skepticism about the benefits that can be expected from “those who affected to trade for the public good”–this argument must be rejected on the grounds of principle. What it amounts to is an assertion that those who favor the taxes and expenditures in question have failed to persuade a majority of their fellow citizens to be of like mind and that they are seeking to attain by undemocratic procedures what they cannot attain by democratic procedures. In a free society, it is hard for “evil” people to do “evil,” especially since one man’s good is another’s evil.

I have, for simplicity, concentrated on the special case of the corporate executive, except only for the brief digression on trade unions. But precisely the same argument applies to the newer phenomenon of calling upon stockholders to require corporations to exercise social responsibility (the recent G.M. crusade, for example). In most of these cases, what is in effect involved is some stockholders trying to get other stockholders (or customers or employees) to contribute against their will to “social” causes favored by activists. Insofar as they succeed, they are again imposing taxes and spending the proceeds.

The situation of the individual proprietor is somewhat different. If he acts to reduce the returns of his enterprise in order to exercise his “social responsibility,” he is spending his own money, not someone else’s. If he wishes to spend his money on such purposes, that is his right and I cannot see that there is any objection to his doing so. In the process, he, too, may impose costs on employees and customers. However, because he is far less likely than a large corporation or union to have monopolistic power, any such side effects will tend to be minor.

Of course, in practice the doctrine of social responsibility is frequently a cloak for actions that are justified on other grounds rather than a reason for those actions.

To illustrate, it may well be in the long-run interest of a corporation that is a major employer in a small community to devote resources to providing amenities to that community or to improving its government. That may make it easier to attract desirable employees, it may reduce the wage bill or lessen losses from pilferage and sabotage or have other worthwhile effects. Or it may be that, given the laws about the deductibility of corporate charitable contributions, the stockholders can contribute more to charities they favor by having the corporation make the gift than by doing it themselves, since they can in that way contribute an amount that would otherwise have been paid as corporate taxes.

In each of these–and many similar–cases, there is a strong temptation to rationalize these actions as an exercise of “social responsibility.” In the present climate of opinion, with its widespread aversion to “capitalism,” “profits,” the “soulless corporation” and so on, this is one way for a corporation to generate goodwill as a by-product of expenditures that are entirely justified on its own self-interest.

It would be inconsistent of me to call on corporate executives to refrain from this hypocritical window-dressing because it harms the foundation of a free society. That would be to call on them to exercise a “social responsibility”! If our institutions, and the attitudes of the public make it in their self-interest to cloak their actions in this way, I cannot summon much indignation to denounce them. At the same time, I can express admiration for those individual proprietors or owners of closely held corporations or stockholders of more broadly held corporations who disdain such tactics as approaching fraud.

Whether blameworthy or not, the use of the cloak of social responsibility, and the nonsense spoken in its name by influential and prestigious businessmen, does clearly harm the foundations of a free society. I have been impressed time and again by the schizophrenic character of many businessmen. They are capable of being extremely far-sighted and clearheaded in matters that are internal to their businesses. They are incredibly short-sighted and muddle-headed in matters that are outside their businesses but affect the possible survival of business in general. This short-sightedness is strikingly exemplified in the calls from many businessmen for wage and price guidelines or controls or income policies. There is nothing that could do more in a brief period to destroy a market system and replace it by a centrally controlled system than effective governmental control of prices and wages.

The short-sightedness is also exemplified in speeches by businessmen on social responsibility. This may gain them kudos in the short run. But it helps to strengthen the already too prevalent view that the pursuit of profits is wicked and immoral and must be curbed and controlled by external forces. Once this view is adopted, the external forces that curb the market will not be the social consciences, however highly developed, of the pontificating executives; it will be the iron fist of Government bureaucrats. Here, as with price and wage controls, businessmen seem to me to reveal a suicidal impulse.

The political principle that underlies the market mechanism is unanimity. In an ideal free market resting on private property, no individual can coerce any other, all cooperation is voluntary, all parties to such cooperation benefit or they need not participate. There are not values, no “social” responsibilities in any sense other than the shared values and responsibilities of individuals. Society is a collection of individuals and of the various groups they voluntarily form.

The political principle that underlies the political mechanism is conformity. The individual must serve a more general social interest–whether that be determined by a church or a dictator or a majority. The individual may have a vote and say in what is to be done, but if he is overruled, he must conform. It is appropriate for some to require others to contribute to a general social purpose whether they wish to or not.

Unfortunately, unanimity is not always feasible. There are some respects in which conformity appears unavoidable, so I do not see how one can avoid the use of the political mechanism altogether.

But the doctrine of “social responsibility” taken seriously would extend the scope of the political mechanism to every human activity. It does not differ in philosophy from the most explicitly collective doctrine. It differs only by professing to believe that collectivist ends can be attained without collectivist means. That is why, in my book Capitalism and Freedom, I have called it a “fundamentally subversive doctrine” in a free society, and have said that in such a society, “there is one and only one social responsibility of business–to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

STARBUCKS ends ‘Race Together’ campaign in stores

Why Starbucks’ “Race Together” Initiative Failed So Spectacularly

The explicit 2 percent ACA surcharge at Buffalo Wild Wings may or may not have been intended as permanent. The restaurant chain’s executives have already cancelled the policy after customers reacted negatively. But there is a lesson to be learned from the surcharge. Government programs have the superficial appearance of being free, but they never are.

The explicit 2 percent ACA surcharge at Buffalo Wild Wings may or may not have been intended as permanent. The restaurant chain’s executives have already cancelled the policy after customers reacted negatively. But there is a lesson to be learned from the surcharge. Government programs have the superficial appearance of being free, but they never are.