5 More Lies in Joe Biden’s 2024 State of the Union Address

The fallout continues over President Joe Biden’s 2024 State of the Union address, and his errors, lies, and misstatements continue to pile up. Here are five more false claims Biden made on Thursday night.

1. Biden Claims He Has Created 15 Million Jobs and 800,000 New Manufacturing Jobs

In speaking about his economic record, Biden boasted of creating “15 million new jobs in just three years,” including “800,000 new manufacturing jobs in America and counting.”

Most of the jobs Joe Biden has taken credit for “creating” were merely jobs destroyed by the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns.

The economy under Joe Biden actually created about one-third that many new jobs: The economy added 5.49 million jobs above pandemic level in three years. President Donald Trump’s economy created 6.7 million jobs in the three years before the pandemic. Similarly, Joe Biden has added 114,000 manufacturing jobs, compared to the pre-pandemic level of February 2020. President Trump created 400,000 manufacturing jobs in the same period.

American workers have enjoyed little of this job growth. The U.S. workforce added 2.9 million foreign-born workers (legal or illegal), while there were 183,000 fewer U.S. citizens in the workforce between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the same period in 2023.

Some of this job growth is illusory, since a total of 8.3 million Americans hold multiple jobs, and 386,000 Americans are working two full-time jobs — a number that reached a 30-year high of 447,000 last September. More than two million people work two (or more) part-time jobs. And the number working-age Americans who are working, the labor force participation rate, remains below pre-pandemic levels.

2. Wages Are Up and Inflation Is Down under Biden?

Joe Biden touted his economy as a boon for middle-class workers, adding, “Wages keep going up. Inflation keeps coming down. Inflation has dropped from 9% to 3% — the lowest in the world and trending lower. … Consumer studies show consumer confidence is soaring.”

Real wages remain lower under Biden, thanks to soaring inflation sparked in part by massive rounds of stimulus-level government spending. Americans under Biden need to earn an extra $11,434 a year to maintain the same level of income they had before he took office. The average American, of course, has not closed the gap.

“Bidenflation” shows up in everyday prices: The cost of dairy products has risen 59 cents since February 2021. A loaf of bread costs more dough — 49 cents a loaf more. Other staples, utilities, and necessities have risen, including chicken (41 cents a pound), a dozen eggs (92 cents), gasoline (72 cents a gallon), home heating gas (29%), and electricity (21%).

Rather than address these concerns, Biden focused on shrinkflation and “junk fees.” Even Biden’s speechwriters felt the need to sell the public on their policy’s relevance, insisting, “It matters. It matters.” Biden’s focus invited withering criticism from his chief rival for the presidency. “Biden talked about the SNICKERS bars, before he talked about the border!” posted former President Donald Trump on Truth Social.

The Biden administration did give some indication of who benefitted from its policies: The White House invited Shawn Fain — president of the United Auto Workers, which had delayed its endorsement of Biden’s reelection — to the State of the Union address.

3. The Myth of Trump’s Muslim Ban

In his section on immigration, Biden attempted to distinguish himself from “my predecessor” by saying, “I will not ban people because of their faith.”

Biden is alluding to President Trump’s so-called “Muslim travel ban.” In December 2015, candidate Trump called for a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what is going on.” Then-President Barack Obama had admitted 12,500 scantly-vetted “refugees” from Syria. Trump also cited widespread, anti-American sentiment and terrorist activity throughout the Islamic world for decades, including a poll of Muslims from the Center for Security Policy which found “25% of those polled agreed that violence against Americans here in the United States is justified as a part of the global jihad.” But he never pursued such a policy in office, using model policies enacted by the Obama-Biden administration.

In his first week in office, Trump signed Executive Order 13769, placing a 90-day moratorium on some immigration from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen. It also required vetting of people hailing from nations whose background checks do not meet U.S. standards. The move was far from unprecedented. Under the Visa Waiver Program Improvement and Terrorist Travel Prevention Act of 2015, Barack Obama imposed similar restrictions on anyone who was “present, at any time” in Iraq, Sudan, Syria, Libya, Somalia, and Yemen in the past four years. Yet activist courts initially ruled Trump could not impose the same policy, eventually accepting an amended version that barred immigration from Iran, Libya, Somalia, North Korea, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen.

In 2020, Trump broadened this net of protection by excluding the terror-tied nations of Kyrgyzstan, Myanmar, Eritrea, Nigeria, Sudan, and Tanzania. (Muslims make up a mere 4% of Myanmar’s population, 0.3% of Venezuela’s population, and officially zero percent of North Korea’s.) The Supreme Court upheld the policy, Presidential Proclamation 9645, in Trump v. Hawaii (2017). Biden rescinded the executive order on his first day in office: January 21, 2021.

The threat proved to be anything but illusory. Authorities arrested a Syrian refugee, 21-year-old Mustafa Mousab Alowemer, for plotting to blow up a Christian church in Pittsburgh, Legacy International Worship Center, to support ISIS.

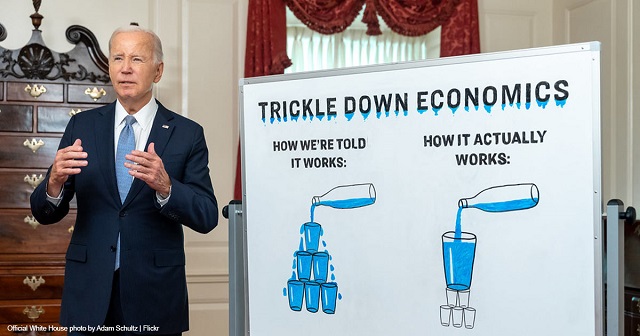

4. Making the Rich ‘Pay Their Fair Share’ of Taxes?

Joe Biden promised to enact “a fair tax code” by “making big corporations and the very wealthy finally begi[n] to pay their fair share. Look, I’m a capitalist. If you want to make, you can make a million or millions of bucks, that’s great. Just pay your fair share in taxes.”

The top 1% of income earners paid 42.3% of U.S. income taxes in 2020, the most recent year available, according to an analysis from the nonpartisan Tax Foundation. The top 10% paid 73.7% of income taxes. All told, the top half of income earners paid 97.7% of all taxes, while the bottom half paid 2.3%.

By contrast, a growing number of Americans paid no income tax. An estimated 57% of Americans paid nothing in federal income taxes in 2021, according to the Tax Policy Center.

By any just reckoning, the wealthiest Americans are paying their fair share of income tax — and a good deal of our share, as well.

5. Biden Has Not Raised Federal Taxes on Anyone Making Less than $400,000?

“Under my plan nobody earning less than $400,000 a year will pay an additional penny in federal taxes,” Biden claimed. “Nobody. Not one penny. And they haven’t yet.”

If Joe Biden has not squeezed more money out of those making less than $400,000, it’s not for lack of trying. Biden and congressional Democrats have endorsed numerous proposals that would have extracted more of the federal budget from those beneath Biden’s alleged income threshold. Those proposals include:

- Expanding the number of items that must be registered under the National Firearms Act, with a $200 fee for each item

- Reinstating the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate and $695-per-person penalty, which President Trump eliminated

- Imposing a carbon and/or methane tax. One proposal would charge companies $1,800 per ton of methane they handle (not emit), with the cost rising 2% above inflation each year

- Increasing corporate taxes, which pass on approximately one-third of increased costs to consumers by raising prices (and another third by reducing payroll costs/hours)

- Hiking cigarette taxes, which fall disproportionately on the working class

The greatest way Biden has funded the federal budget at the expense of the middle class is through inflation. As Henry Hazlitt explained in his classic book “Economics In One Lesson”:

“Inflation is a form of taxation. It is perhaps the worst possible form, which usually bears hardest on those least able to pay. … It discourages all prudence and thrift. It encourages squandering, gambling, reckless waste of all kinds. It often makes it more profitable to speculate than to produce.”

Here is the previous collection of “14 Lies and Myths in Joe Biden’s 2024 State of the Union Address.”

AUTHOR

Ben Johnson

Ben Johnson is senior reporter and editor at The Washington Stand.

RELATED ARTICLE: More Misleading White House Statistics on Unemployment

POST ON X:

🚨BREAKING: "Donald Trump’s new leadership team over at the RNC began cutting dozens of staffers from their positions. It appears a major shakeup now underway at the RNC following Lara Trump’s recent ascension to RNC co-chair" pic.twitter.com/EjL7mc8fAw

— Benny Johnson (@bennyjohnson) March 11, 2024

EDITORS NOTE: This Washington Stand column is republished with permission. All rights reserved. ©2024 Family Research Council.

The Washington Stand is Family Research Council’s outlet for news and commentary from a biblical worldview. The Washington Stand is based in Washington, D.C. and is published by FRC, whose mission is to advance faith, family, and freedom in public policy and the culture from a biblical worldview. We invite you to stand with us by partnering with FRC.