UN Deletes Article Titled ‘The Benefits of World Hunger.’ Was It Real or Satire?

The author of the article in question told FEE it was not a parody.

UN Chronicle, the official magazine of the United Nations, recently deleted a 2008 article titled “The Benefits of World Hunger.”

The article, which now leads to an “error page,” was written by George Kent, a now retired University of Hawaii political science professor. In the article, Kent argued that hunger is “fundamental to the working of the world’s economy.”

“Much of the hunger literature talks about how it is important to assure that people are well fed so that they can be more productive,” Kent wrote. “That is nonsense. No one works harder than hungry people. Yes, people who are well nourished have greater capacity for productive physical activity, but well-nourished people are far less willing to do that work.”

UN Chronicle deleted the article after it began to cause a stir on social media. The magazine said Kent’s article should not be taken literally, contending that it was a work of parody.

“This article appeared in the UN Chronicle 14 years ago as an attempt at satire and was never meant to be taken literally. We have been made aware of its failures, even as satire, and have removed it from our site.”

In the face of looming food/energy shortages caused by disastrous climate policies, the UN says “Hungry people are the most productive people, especially where there is a need for manual labour.”

Yeah. Starvation does that.

Don’t worry. It’s good for you.https://t.co/cI7gFchtD8

— The Real Andy Lee Show (@RealAndyLeeShow) July 6, 2022

Satire or Literal?

At first glance, there seems to be little reason to doubt the United Nations. As some writers have noted, previous works written by Kent include Ending World Hunger, The Political Economy of Hunger: The Silent Holocaust, and Freedom from Want: The Human Right to Adequate Food.

These titles hardly suggest that Kent sees global hunger as a good thing. In light of this, some contended that he was taking an approach not unlike Jonathan Swift, whose famous essay “A Modest Proposal” cheekily argued that Irish families should alleviate their mean condition by selling excess children to the wealthy for food.

After reading the UN’s tweet, Yahoo’s report, and several other pieces of commentary on the subject, I initially agreed that Kent’s article likely was written as satire. However, closer examination and a brief conversation with Kent revealed that is not the case.

First, it’s important to note that Kent himself denies the article was intended as a form of satire.

“I don’t think the UN would have published it if they thought it was satire or advocacy,” Kent told Climate Depot in a recent phone interview.

In the interview, Kent explains he was not advocating global hunger but was intending to be “provocative” by saying certain individuals and institutions benefit from global hunger.

UN journal article explains ‘The Benefits of World Hunger’ – ‘Hunger has great positive value…Hungry people are the most productive people’ –

UN deletes essay after outcry | Climate Depot https://t.co/1XNGHDpHGQ

— Marc Morano (@ClimateDepot) July 7, 2022

“No, it is not satire,” Kent told Marc Morano, founder and editor of Climate Depot. “I don’t see anything funny about it. It is not about advocacy of hunger.”

I reached out to Kent and asked if the quotes were accurate, and he told me they were, adding that he intends to publish a paper this fall that will further detail his views.

“Marc understood me very well,” Kent told me in an email. “I hope my current paper on who benefits from hunger helps to make my position clear to everyone involved in this discussion.”

Additionally, the article’s concluding paragraph supports Kent’s claim that the work was not designed as either satire or advocacy. A careful reading of the text suggests Kent is being quite literal when he writes that some people benefit from global hunger.

“For those of us at the high end of the social ladder, ending hunger globally would be a disaster. If there were no hunger in the world, who would plow the fields?” Kent wrote. “Who would harvest our vegetables? Who would work in the rendering plants? Who would clean our toilets? We would have to produce our own food and clean our own toilets. No wonder people at the high end are not rushing to solve the hunger problem. For many of us, hunger is not a problem, but an asset.”

One senses in these words disapproval. The global poor exist because the wealthy require them to exist. Global hunger exists because humans are simply not doing the moral and necessary things to eradicate it.

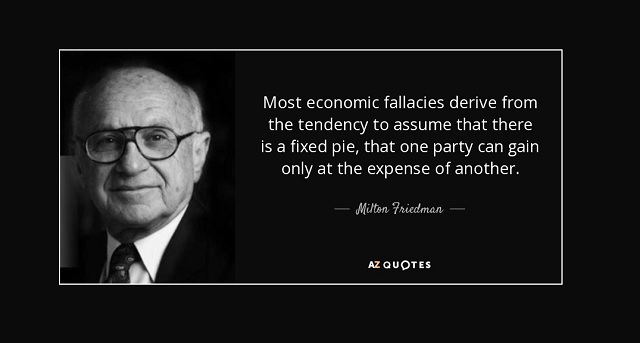

But what are those things? A glimpse at Kent’s 2011 Ending Hunger Worldwide offers a clue. In the summary of the book, readers are told the keys to tackling global hunger are “building stronger communities” and challenging “dominant market-led solutions.”

In Kent’s view, one gathers, global hunger is not a complex problem that is being addressed by free market capitalism; it’s a moral one that requires empowering intellectuals like Kent to solve it.

It’s also worth noting that reviews of Kent on Rate My Professor—which gives him a rating of 1.9 out of 5—suggest he’s, well, perhaps a bit of an ideologue.

“Avoid this man with your life. Very opinionated and if your opinion differs, you will fail. He’s the worst professor i’ve had,” one reviewer wrote.

“Horrible professor if you are not politically aligned with his values you WILL FAIL,” another contended.

“Very opinionated and unhelpful,” opined another. “Very critical and extremely boring. Unsupportive and irritating.”

Alleviating Global Hunger and the Rise of ESG

Whether Kent is a good professor or not, or whether his article was satire or literal, are questions that ultimately do not matter a whole lot in the larger scheme of things. What does matter are the policies that cause global hunger and the policies that alleviate global hunger.

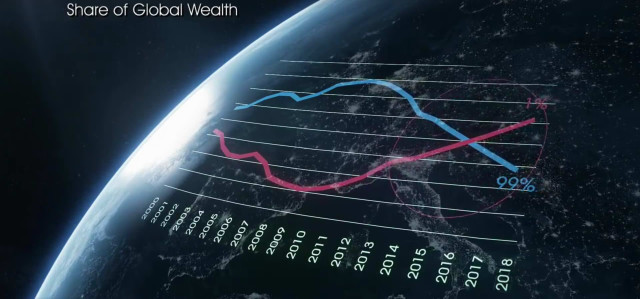

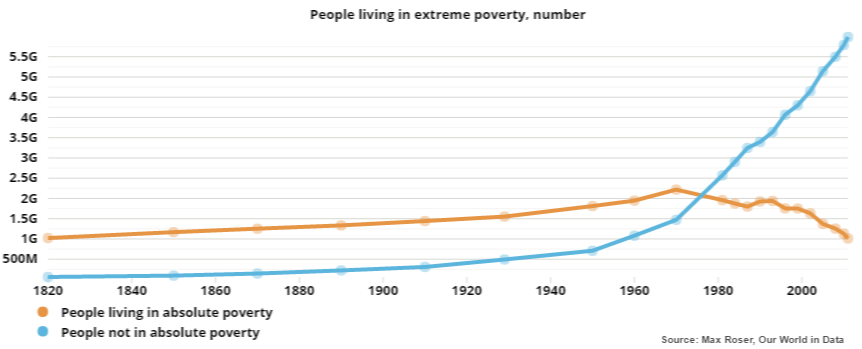

And on this front, there has been stunning progress in recent decades. As Our World in Data shows, the percentage of undernourished people in developing countries has plummeted in recent years, falling from 35 percent in 1970 to 13 percent in 2015.

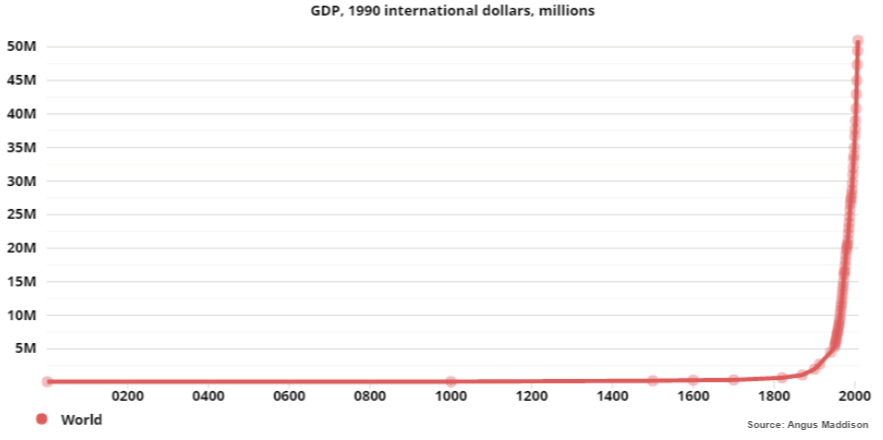

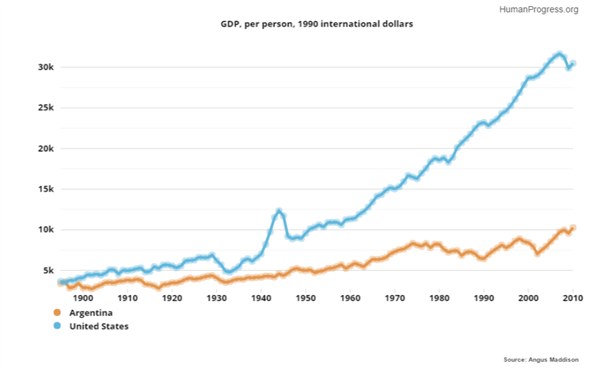

How this happened is not a mystery. As economist Bob Murphy noted in FEE.org, the proliferation of free market capitalism has “gone hand-in-hand with rapid and unprecedented increases in human welfare.”

“As the World Bank reports, the global rate of ‘extreme poverty’ (defined as people living on less than $1.90 per day) was cut in half from 1990 to 2010. Back in 1990, 1.85 billion people lived in extreme poverty, but by 2013, the figure had dropped to 767 million—meaning the number of those living on less than $1.90 per day had fallen by more than a billion people.’”

Ironically, no better example of this can be found in recent decades than China, which has achieved nothing short of an economic miracle in recent decades. China saw its percentage of underweight children fall from 19 percent in 1987 to 2.4 percent in 2013. As recently as 1990, 66 percent of Chinese people lived in extreme poverty. By 2015, that figure was less than one percent.

How did China achieve this economic miracle? By pivoting to privatization following the death of Party Chairman Mao Zedong (1893-1976), as I pointed out in 2019.

In 1979, China adopted its “household responsibility system,” giving many farmers ownership of their crop for the first time. This was followed by Communist Party leaders opening China to foreign investment, curbing price controls and protectionism, and implementing mass privatization of its economy.

The “market-led solutions” that Kent has disparaged have worked wonders for hunger alleviation. The same cannot be said for initiatives hatched by the central planners at the United Nations, the organization that published Kent’s controversial article on hunger.

Sri Lanka’s current food crisis stems directly from an effort to shift the country’s agriculture sector to organic farming, which saw the import of fertilizers banned and led the country to become an importer of rice instead of an exporter virtually overnight.

Many writers and thinkers are blaming Sri Lanka’s crisis on the global rise of ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance), which was started in 2004 under the auspices of—you guessed it—the United Nations to encourage “sustainable development.”

A food, energy, and financial crisis has brought down Sri Lanka's government. But the underlying cause is the fact that the nation's political leaders had fallen under the spell of green elites peddling “ESG” and banning modern fertilizers.https://t.co/En6rbDrsYu

— Michael Shellenberger (@ShellenbergerMD) July 10, 2022

And people are right to blame ESG. Writing for the World Economic Forum in 2016, economist Joseph Stiglitz said “Sri Lanka may be able to move directly into… high-productivity organic farming…”

Sri Lanka did. By doing so, the nation earned an ESG score of 98/100—and caused a food crisis that resulted in one president’s resignation and food insecurity for millions of people.

This is a tragedy. And while George Kent is clearly wrong—there are no benefits to world hunger—one begins to understand why his 15-year-old article published by the United Nations is suddenly sparking so much interest

It’s not just Sri Lanka, after all. The Netherlands, Canada, and other countries are all making headlines with food schemes that are likely to goose their ESG score—but cause serious problems at a time when global hunger is on the rise for the first time in decades.

If our population were the same size as 500 years ago we'd be poorer and more polluted. Humans solve problems. https://t.co/3NnZVBNMgX

— Peter Jacobsen (@PeterPashute) July 19, 2022

In light of current global policies, anti-population rhetoric, and the track record of twentieth century collectivist food schemes—Holodomor, Cambodia, and Mao’s Great Leap Forward, which saw tens of millions starve to death because of government policies—George Kent’s “The Benefits of World Hunger” article hit too close to home.

(Editor’s Note: We’ve posted George Kent’s 2008 entire article below since the United Nations removed the article from their site so readers can determine for themselves Kent’s purpose in writing the article.)

We sometimes talk about hunger in the world as if it were a scourge that all of us want to see abolished, viewing it as comparable with the plague or aids. But that naïve view prevents us from coming to grips with what causes and sustains hunger. Hunger has great positive value to many people. Indeed, it is fundamental to the working of the world’s economy. Hungry people are the most productive people, especially where there is a need for manual labour.

We in developed countries sometimes see poor people by the roadside holding up signs saying “Will Work for Food.” Actually, most people work for food. It is mainly because people need food to survive that they work so hard either in producing food for themselves in subsistence-level production, or by selling their services to others in exchange for money. How many of us would sell our services if it were not for the threat of hunger?

More importantly, how many of us would sell our services so cheaply if it were not for the threat of hunger? When we sell our services cheaply, we enrich others, those who own the factories, the machines and the lands, and ultimately own the people who work for them. For those who depend on the availability of cheap labour, hunger is the foundation of their wealth.

The conventional thinking is that hunger is caused by low-paying jobs. For example, an article reports on “Brazil’s ethanol slaves: 200,000 migrant sugar cutters who prop up renewable energy boom”. While it is true that hunger is caused by low-paying jobs, we need to understand that hunger at the same time causes low-paying jobs to be created. Who would have established massive biofuel production operations in Brazil if they did not know there were thousands of hungry people desperate enough to take the awful jobs they would offer? Who would build any sort of factory if they did not know that many people would be available to take the jobs at low-pay rates?

Much of the hunger literature talks about how it is important to assure that people are well fed so that they can be more productive. That is nonsense. No one works harder than hungry people. Yes, people who are well nourished have greater capacity for productive physical activity, but well-nourished people are far less willing to do that work.

The non-governmental organization Free the Slaves defines slaves as people who are not allowed to walk away from their jobs. It estimates that there are about 27 million slaves in the world, including those who are literally locked into workrooms and held as bonded labourers in South Asia. However, they do not include people who might be described as slaves to hunger, that is, those who are free to walk away from their jobs but have nothing better to go to. Maybe most people who work are slaves to hunger?

For those of us at the high end of the social ladder, ending hunger globally would be a disaster. If there were no hunger in the world, who would plow the fields? Who would harvest our vegetables? Who would work in the rendering plants? Who would clean our toilets? We would have to produce our own food and clean our own toilets. No wonder people at the high end are not rushing to solve the hunger problem. For many of us, hunger is not a problem, but an asset.

AUTHOR

Jon Miltimore

Jonathan Miltimore is the Managing Editor of FEE.org. His writing/reporting has been the subject of articles in TIME magazine, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, Forbes, Fox News, and the Star Tribune. Bylines: Newsweek, The Washington Times, MSN.com, The Washington Examiner, The Daily Caller, The Federalist, the Epoch Times.

EDITORS NOTE: This FEE column is republished with permission. ©All rights reserved.