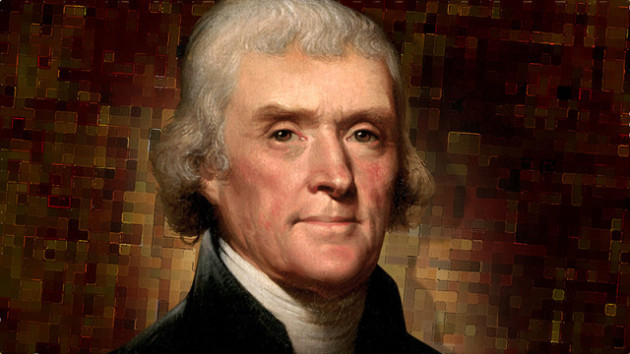

Salon.com gets it wrong on Thomas Jefferson’s Quran and Islam

Denise Speelberg in her column “Our Founding Fathers included Islam” states, “Thomas Jefferson didn’t just own a Quran — he engaged with Islam and fought to ensure the rights of Muslims.” The basis of Speelberg’s column is Thomas Jefferson quoting “A Letter Concerning Toleration” by John Locke who in 1689 wrote, “Nay, if we may openly speak the truth, and as becomes one man to another, neither Pagan nor Mahometan, nor Jew, ought to be excluded from the civil rights of the commonwealth because of his religion.”

Note that Locke groups “Pagan and Mahometan” together. Locke is speaking about civil (legal) rights in England and the Commonwealth.

In Locke’s letter Mahometan is mentioned only once. Jew or Jewish are mentioned fifteen times. Locke was more concerned about tolerance toward the Jews. Locke begins his letter with, “Since you are pleased to inquire what are my thoughts about the mutual toleration of Christians in their different professions of religion, I must needs answer you freely that I esteem that toleration to be the chief characteristic mark of the true Church.” What is the true Church to which Locke refers? The Church of England.

To whom is the letter written? Answer: The members of the English Parliament in 1689.

Parliament of England.

Locke’s letter was directed at the 1689 Convention Parliament, an irregular assembly of the Parliament of England. It was the Convention Parliament, which in 1689, issued a Bill of Rights; established a constitutional monarchy in Britain; bared Roman Catholics from the throne; codified William III and Mary II becoming joint monarchs of England and Scotland (to1694), passed the Toleration Act granting freedom of worship to dissenters in England; and created the Grand Alliance of the League of Augsburg, England, and the Netherlands.

The Toleration Act of 1689 allowed freedom of worship to Nonconformists who had pledged to the oaths of Allegiance and Supremacy and rejected transubstantiation, i.e., Protestants who dissented from the Church of England such as Baptists and Congregationalists but not to Catholics. Nonconformists were allowed their own places of worship and their own teachers, if they accepted certain oaths of allegiance. It purposely did not apply to Catholics, nontrinitarians and atheists. The Act continued the existing social and political disabilities for Dissenters, including their exclusion from political office and also from universities.

Our forefathers were “the dissenters” excluded from public office and universities. They came to America seeking political and religious freedom. All were Christians.

Speelberg writes, “At a time when most Americans were uninformed, misinformed, or simply afraid of Islam, Thomas Jefferson imagined Muslims as future citizens of his new nation. His engagement with the faith began with the purchase of a Qur’an eleven years before he wrote the Declaration of Independence.” The problem is Speelberg’s statement is simply not true. Jefferson engaged the Mahometans alright but not in the way presented by Speelberg. While true Jefferson owned a Qu’ran, it was to fight against the Barbary pirates and Islam, not embrace them.

Gerard W. Gawalt in “America and the Barbary Pirates: An International Battle Against an Unconventional Foe” writes:

Ruthless, unconventional foes are not new to the United States of America. More than two hundred years ago the newly established United States made its first attempt to fight an overseas battle to protect its private citizens by building an international coalition against an unconventional enemy. Then the enemies were pirates and piracy. The focus of the United States and a proposed international coalition was the Barbary Pirates of North Africa.

Pirate ships and crews from the North African states of Tripoli, Tunis, Morocco, and Algiers (the Barbary Coast) were the scourge of the Mediterranean. Capturing merchant ships and holding their crews for ransom provided the rulers of these nations with wealth and naval power. In fact, the Roman Catholic Religious Order of Mathurins [Order of Trinitarians] had operated from France for centuries with the special mission of collecting and disbursing funds for the relief and ransom of prisoners of Mediterranean pirates.

Regarding Thomas Jefferson’s opinion of these Mahometans Gawalt found:

Thomas Jefferson, United States minister to France, opposed the payment of tribute, as he later testified in words that have a particular resonance today. In his autobiography Jefferson wrote that in 1785 and 1786 he unsuccessfully “endeavored to form an association of the powers subject to habitual depredation from them. I accordingly prepared, and proposed to their ministers at Paris, for consultation with their governments, articles of a special confederation.” Jefferson argued that “The object of the convention shall be to compel the piratical States to perpetual peace.” Jefferson prepared a detailed plan for the interested states. “Portugal, Naples, the two Sicilies, Venice, Malta, Denmark and Sweden were favorably disposed to such an association,” Jefferson remembered, but there were “apprehensions” that England and France would follow their own paths, “and so it fell through.”

Paying the ransom would only lead to further demands, Jefferson argued in letters to future presidents John Adams, then America’s minister to Great Britain, and James Monroe, then a member of Congress. As Jefferson wrote to Adams in a July 11, 1786, letter, “I acknolege [sic] I very early thought it would be best to effect a peace thro’ the medium of war.” Paying tribute will merely invite more demands, and even if a coalition proves workable, the only solution is a strong navy that can reach the pirates, Jefferson argued in an August 18, 1786, letter to James Monroe: “The states must see the rod; perhaps it must be felt by some one of them. . . . Every national citizen must wish to see an effective instrument of coercion, and should fear to see it on any other element than the water. A naval force can never endanger our liberties, nor occasion bloodshed; a land force would do both.” “From what I learn from the temper of my countrymen and their tenaciousness of their money,” Jefferson added in a December 26, 1786, letter to the president of Yale College, Ezra Stiles, “it will be more easy to raise ships and men to fight these pirates into reason, than money to bribe them.”

Ambassadors Jefferson and Adam efforts to form an international coalition to fight the Barbary pirates failed. When Jefferson became president in 1801 he refused to accede to Tripoli’s demands for an immediate payment of $225,000 and an annual payment of $25,000. The pasha of Tripoli then declared war on the United States. President Jefferson dispatched a squadron of naval vessels to the Mediterranean.

Today Jefferson and Adams, for their efforts, would be called by some “Islamophobes”. President Jefferson had a Qu’ran in order to understand America’s enemies in North Africa, not to embrace them. Jefferson understood that when tolerance of barbarism becomes a one way street it leads to cultural suicide.

Perhaps Speelberg needs to study English and American history? Or is she trying to rewrite American history to fit her political narrative?

RELATED: President Thomas Jefferson and the Barbary Pirates by Robert F. Turner