Downplaying Zionism

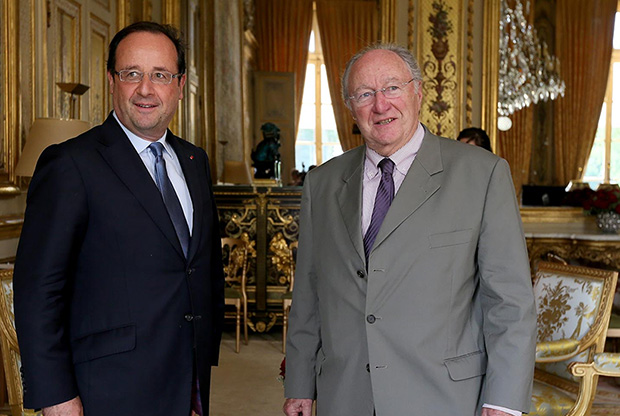

In mid-December, France’s President François Hollande held a reception at the Elysée palace in honor of the 70th anniversary of the CRIF, as the umbrella organization of French Jews is known. Hollande, whose delivery is often wooden and halting, was unusually at ease with his guests and made sure to note in his remarks that he was celebrating “by extension, all the Jews in France.”

The abiding impression of President Hollande’s substantial address—close to 20 minutes—was that therépublique of diversity could not ask for a better element than the Jews. At a time when thorny issues of immigration and integration of the growing Muslim population threaten to disturb the peace in France, Hollande expressed appreciation for a community that is both an integral part of the history of France—the CRIF, he noted, was created in 1943, during the Nazi occupation, alongside the Conseil National de la Résistance—and, by virtue of the tens of thousands of North African Jews who arrived in France in the 1960s, a model of integration. Hollande also renewed his public promises to combat the rising tide of anti-Semitism that plagues Jews in France today, and he spoke about his November state visit to Israel, describing the country as a refuge. “Your attachment to Israel is normal,” he said. “You don’t have to apologize for it.”

And yet that appears to be what the president of the CRIF, Roger Cukierman, is doing. At a private luncheon with a handful of journalists one week before the anniversary celebration, Cukierman—a banker—outlined a “new look” for the organization, which he previously headed for two terms, starting in 2001. During the six-year hiatus between the end of his last term, in 2007, and his re-election this past spring, he said, the CRIF has come to be seen “an annex to the Israeli embassy … an association of right-wing fascists notorious for their unconditional support of the Israeli government.” That image, he went on, “does not correspond to reality.”

Cukierman cited the organization’s endorsement of the Geneva agreement with Iran as an example of nonalignment. “We see the agreement as a positive step that will preclude military action for the next six months and give the Iranian government time to reconsider its nuclear weapons program,” he said. “Seeing that the cost of sanctions is too high, they might decide, like Qaddafi, to renounce and join the concert of nations.”

It’s an ironic move for a group whose acronym refers to its original name—the Conseil Représentatif des Israélites de France—which incorporated the euphemism Israélites, which was then the polite way of designating Jews. In its early years, the organization linked French Jews of all political persuasions, religious and secular, to join in the resistance against mass arrests and deportations and then in the postwar years to assist survivors and help rebuild the Jewish community. In 1972, the organization changed its official name to Conseil représentatif des institutions juives de France. Cukierman readily acknowledges that “anti-Zionism is the elegant way to be anti-Semitic on the Left today”—but nevertheless seems convinced that by soft-pedaling Zionism, the CRIF will be more effective in its combat against anti-Semitism.

As the assembled journalists enjoyed a lunch of foie gras, Mediterranean chicken with rice, and fresh fruit salad, Cukierman went on to describe the troubling climate that prevails in France today. His first term as president of the CRIF coincided with the Second Intifada, the Sept. 11 attacks, and the American-led war in Iraq. Quantitatively, he argued, anti-Semitism is certainly not worse now than it was then. Nevertheless, the perception of a hostile environment has increased—most recently evidenced by the ongoing furor surrounding the comedian Dieudonné M’bala M’bala, whose Nazi-inspired quenelle gesture has gone viral.

Jews, he went on, are the target of hostility from both left and right, and from top to bottom. Though Marine Le Pen has cleaned up the image of the populist, right-wing National Front, its anti-Semitic roots are visible just below the surface. On the left, there are anti-Zionist elements in the Communist and Green parties that have been crucial partners in Hollande’s governing coalition, and there is no evidence of efforts to counter their participation in dubious causes. He noted the continuing spread of the BDS movement, which is officially aimed at Israeli imports but which also affects locally produced kosher products in French supermarkets.

Jewish life in France today is stretched to extremes: unlivable for some in some ways and at some times; vibrant, satisfying, and respected in other ways and at other times. The annual Dîner du CRIF is a glittering event that brings together everyone who is anyone, including, usually, the president of the republic or the prime minister—and sometimes both. Yet, for some, of course, the gala inspires fantasies of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion: a display of power by a group that is a tiny minority, just 0.5 percent of the French population.

Cukierman knows this. As an official of the World Jewish Congress, he has long been devoted to Zionism and to the idea of a common Jewish community. In 2003, he set off a firestorm at the CRIF gala by denouncing a so-called “brown-green-red alliance” joining fascists, the far Left, and Islamists in an “anti-globalization, anti-capitalist, anti-American, anti-Zionist current … a new recipe for old [anti-Semitic] stereotypes.”

During his first term, Cukierman had to deal with the stubborn denial of anti-Semitism from the government of Jacques Chirac and Lionel Jospin while Jews were subject to the worst attacks since the days of Vichy. Cukierman was himself criticized in some quarters for his failure to publicly recognize the anti-Semitic motive for the murder of the popular DJ Sébastien Selam in November 2003 by his Muslim neighbor Adel Boumedienne, who slashed his throat, nearly beheading him, and gouged out his eyes. Three years later, in 2006, Ilan Halimi was kidnapped, held hostage for three weeks, and tortured to death by the Gang of Barbarians, led by the unrepentant anti-Semite Youssouf Fofana.

And most recently, in addition to the quenelle, France has also been subject to a flood of anti-Semitic hashtags on Twitter. These jokes, many have argued, have nothing to do with Israel or Zionism. Neither do the resolution passed by the Council of Europe associating ritual circumcision with female genital mutilation or efforts in several European countries to stigmatize kosher slaughter as savage.

Cukierman’s comments at the press luncheon, which were published by Stéphanie Le Bars in Le Monde, set off a debate within the French Jewish community. A few days before Christmas, Gilles-William Goldnadel, the founder of the French free-speech group Lawyers Without Borders and president of the France-Israel association, published an “invitation to a fraternal dialogue” in which he described Cukierman’s position as “an intellectual and moral capitulation” and strategic error.

There is, in any case, little chance that a “Don’t pick on me, I’m Jewish not Israeli” attitude will prevail in France. French Jews are widely known for being committed Zionists. Beyond the 59 percent increase in French aliyah this year, statistics do not include the thousands of families that live with one foot in France, another in Israel. Geographically, genealogically, politically, and sentimentally French Jews are connected to Israel—and it is unlikely they will be influenced by tactical considerations to downplay their Zionism anytime soon.