Top-down Parental Involvement: Another federal education boondoggle?

As the nation observed the 50th anniversary of President Johnson’s War on Poverty in early January, the 2014 Georgia Family Engagement Conference here drew over 1,200 participants, up from 800 at the inaugural state conference in 2012. About a dozen states have held such confabs, pursuant to the “Parental Involvement” section of Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, an arm of the War on Poverty that sends federal funds to low-income-area schools in hopes of “equalizing” so-called educational outcomes.

About a third of the participants in the conference were parent volunteers; those I met were impressive in their dedication and length of service. Most in attendance, however, were professionals—state or local education officials, administrators of grant-funded nonprofits, education researchers, and so on.

An important thrust of the conference was to share strategies for fulfilling the federal mandates that go along with Title I money. Parental engagement receives 1 percent of the total Title I pot, which has risen from $3.2 billion in 1980 to $14.4 billion in the budget just passed. Naturally, that money comes with strings, many of them defined in legal jargon that is difficult for your average parent volunteer to understand.

Ken Banter, Title I director for the rural Peach County Schools, confirmed, “The monitoring piece with federal funds is humongous.” A whole session—“What is a Title I School and What Does that Mean for My Child?”—was devoted to basic explanations from two Georgia Department of Education Title I specialists. Judy Alger asserted, “We know through research that poverty equals low performance” (though when I inquired about the research, she suggested Google). Therefore, Title I designation is “a good thing” for a school, sending it more teachers, more literacy and math coaches, more tutors, and more technology. But, Alger warned, “They give us money because they want to tell us how to do things.” For instance, noted Kathy Pruett, under Targeted Assistance Programs, snacks are okay, meals not.

One string requires that parents be recruited to review the Comprehensive Local Education Agency Improvement Plan (CLIP). Ken Banter shared how he tried to make things easy for parents by dividing the 65-page CLIP into 2-page sections, preparing a 5-page handout on acronyms, and giving away donated book bags of school supplies to volunteers. As a result, he said, participation in his 4,000-student district increased from 10 parents in 2012 to more than 150 in 2013.

CaDeisha Cooper, Title I director for the Candler County Schools, said of her summer leadership program, “What you do is what the law requires you to do.” She makes a particular effort to translate the legal gobbledygook into simple language for parents.

The problem of parents’ difficulty understanding government programs arose again at the only panel on the controversial new federally orchestrated education standards, “Giving Students a Chance: Understanding the Common Core Georgia Performance Standards.” The panelists all represented organizations that support Common Core: Lisa-Marie Haygood and Donna Kosicki are president-elect and past president of the Georgia PTA, respectively, and Dana Rickman is director of policy and research at the Georgia Partnership for Excellence in Education. Kosicki led a word-association exercise on feel-good terms like “relevance.” Haygood offered that “it is important to stop switching gears” and not abandon Common Core.

Rickman showed a number of slides demonstrating Georgia’s lagging college readiness. When I asked how Common Core will help, Rickman replied, “It is believed that the new standards will lead to improvement” and directed me to the Fordham Foundation’s website. Fordham, like the PTA, has received funds from the Gates Foundation, the biggest private funder of Common Core.

The conference drew dozens of vendors, many of them nonprofits. There was Building Positive Families, Watch D.O.G.S. (Dads of Great Students), and groups promoting health, art, and the prevention of drug abuse. Some paid a vendor fee to put on a workshop. At Family First’s workshop, “Increasing Male Involvement and Engaging Dads in Schools,” Andy Mayer described the group’s services for schools, such as “All-Pro Dad” breakfasts and exercises that get dads (or father figures) “connecting,” with prompts like, “I’m proud of you because. . . .” Increased PTA membership is deemed a measure of success. The PTA is the primary booster of the Family Engagement in Education Act of 2013, which would provide no new funding but lots of new instructions for how to spend it—in the words of a PTA backgrounder, “a roadmap for investment in sustainability of practice in family engagement in education” by schools, localities, and states.

The Athens conference was funded by nonprofit and for-profit vendors and exhibitors, as well as sponsors and registrants, according to Michelle Tarbutton Sandrock, parent engagement program manager for the Georgia Department of Education. Schools and districts, however, used Title I funds to send representatives to the gathering.

Georgia College economics professor Ben Scafidi says the costs to the public for parental engagement personnel and activities are difficult to isolate. What is clear, as he noted in his 2012 report “The School Staffing Surge,” is that the United States spends more than other nations on non teaching staff. Between 1970 and 2010, non teaching staff positions increased 138 percent nationally, while teaching positions increased 60 percent and student enrollment rose only 7.8 percent, according to the Heritage Foundation. How much did it help? Between 1992 and 2008, math scores for 17-year-olds remained constant, and reading performance declined.

Amid all the presentations and exhibits, conspicuously lacking was research establishing that government-sponsored parental involvement improves learning. When I asked Tarbutton Sandrock about this, she referred me to Karen Mapp of the Harvard Family Research Project and Anne Henderson, senior consultant for community organizing and engagement at the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University. Both are advocates for government-funded parental engagement.

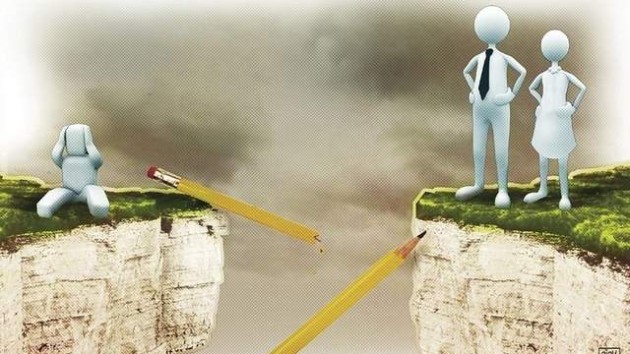

Fifty years into the War on Poverty, a vastly expanded, federally funded bureaucracy works to manage parents’ involvement in their own children’s schools. Meanwhile, educational attainment stagnates and poverty grows.

EDITORS NOTE: This column originally appeared in The Weekly Standard. Photo courtesy of the Marco Island Sun Times a Gannett Company.

RELATED COLUMN: More parent involvement leads kids to behave and do better in school

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] […]

Comments are closed.