Frank Woolworth and the Minimum Wage by DANIEL J. SMITH, ZAC THOMPSON

Woolworth’s five-and-dime stores pioneered a discount retailing model that was a godsend to consumers and employees across the country. Minimum-wage laws, however, would have kept their founder, Frank Woolworth, from even getting close enough to the retail business to have his moment of entrepreneurial insight.

Woolworth was born in 1852 in upstate New York to farmers. By contemporary standards, he grew up poor and deprived. He spent the vast majority of his childhood pitching hay, shoveling manure, feeding farm animals, and performing other duties required by his family’s farm. Little Frank’s farm life was so demanding at times that he had to sacrifice time spent in school.

By his 16th birthday, Woolworth knew he wanted out. His mother had saved for furthering Frank’s education, so he completed a semester of bookkeeping classes in nearby Watertown, New York. But classroom experience wasn’t enough; he had no relevant experience and failed to latch on anywhere. Frank spent an additional five years trapped in the life he longed to escape, until he heard of an opening at a dry goods store, Augsbury & Moore, in Watertown.

Uncertain and skeptical of Woolworth’s capabilities, Moore agreed to take a chance and bring Woolworth on for basic grunt work. When Woolworth asked how much he would be paid, Moore replied in an astonished tone, “Pay you? Why you ought to pay us for teaching you the business! When you go to school you have to pay fees. Well, we won’t charge you any tuition fee but you’ll have to work for nothing until we can decide if you are worth anything and how much.”

Initially, Moore wanted Woolworth to work for free for six months. While his lack of experience made opportunities hard to come by, Woolworth made up for it in part by negotiating the trial period down to three months, followed by a wage of $3.50 per week. It seems unfair at best, by contemporary standards, but Moore actually did Woolworth a favor by putting him on the course to vast wealth.

It got off to a rocky start. The inexperienced Woolworth habitually blundered during the trial period, requiring Moore to devote significant resources to training him and placating inadequately-served customers. But after the first three months, Woolworth earned steady, small increases, eventually attaining a comfortable $6 per week.

A minimum-wage policy would have precluded even this. With a minimum wage policy, competition among workers favors those with more experience, better education, and more connections. Should an employer have to choose between two workers, both of whom would be legally required to earn the same wage, any self-interested businessperson would choose the more qualified and certain choice, rather than bet on an inexperienced or uncertain worker. To Frank’s advantage, no such policy existed, and he could compete with higher-skilled workers by offering his services for lower compensation.

Woolworth made the most of his opportunity. Often working 82-hour work weeks throughout those early years, Woolworth consistently added skills, proving himself more than capable of clerical work, interior decorating, housekeeping, and bookkeeping. His newfound experience in business caught the eye of other employers, which brought him offers of higher wages. Arguably for the first time in his life, Woolworth was in control of his own destiny.

Leaving Augsbury & Moore to work for higher wages, Woolworth continued life in small business and recalled how Augsbury & Moore had a section of goods specifically designated to be sold at five cents per item. Designed to dispose of low quality goods or supplement consumers’ larger purchases, the five-cent section of Augsbury & Moore remained obscure and uninteresting, but Woolworth pondered the concept with intense curiosity. He realized that a real market existed for a store that exclusively sold five-cent goods. Approaching his former boss, Moore, for assistance, Woolworth managed to secure capital and a store location in Utica, New York, to experiment with his new idea. “Woolworth’s Great Five Cent Store,” launched in 1878, was initially a failure, but Woolworth kept at it. By 1881, Woolworth, along with his brother Charles, had developed a business model incorporating 10-cent merchandise and the chain had begun to flourish.

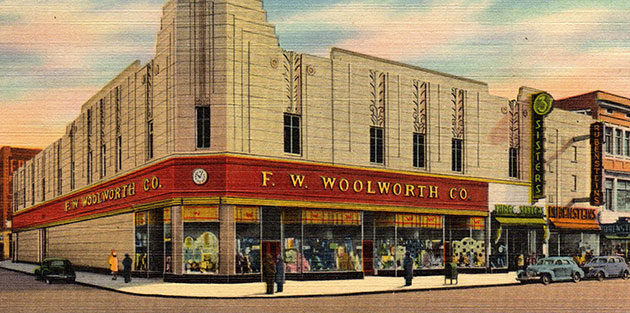

Woolworth’s 5 & 10 Cent Store quickly captured large sections of the retail market, allowing Woolworth to expand his business. Reaching out into larger cities, Frank began opening larger stores with a more diverse selection of goods. At the end of his first year in business in 1879, Woolworth had two stores in operation with gross sales of $12,024. Within 30 years Woolworth’s Stores had well over 200 locations, with gross sales of over $23 million. Woolworth’s business brought great wealth to him and his family, but more importantly it enriched the lives of millions of consumers and employees.

Domestically, Woolworth’s turned into a miracle-maker for the average poor consumer. Woolworth’s Stores made available cheap goods to lower-income individuals, particularly immigrants, improving their standard of living. It also employed thousands of people facing situations similar to young Frank’s.

Woolworth himself was well aware of this. In his annual letter in 1892, Woolworth wrote, “When a clerk gets so good she can get better wages elsewhere, let her go—for it does not require skilled and experienced sales ladies to sell our goods . . . It may look hard to some of you for us to pay such small wages but there are lots of girls that live at home that are too proud to work in a factory or do housework. They are glad of a chance to get in a store for experience if nothing more and when they get experience they are capable of going to a store which can afford to pay good wages. But one thing is certain: We cannot afford to pay good wages and sell goods as we do not, and our clerks ought to know that.”

Woolworth employees either moved up within the company or moved on to better opportunities outside of it. Alvin Edgar Ivie joined Woolworth’s at age 16 as an office assistant and retired decades later with both a city mansion and country estate. The son of a farmer, Charles C. Griswold, worked his way up to the position of Woolworth store inspector, writing detailed reports of stores for Frank Woolworth. In fact, a major motion picture and book in the 1920s, “The Girl from Woolworth’s,” actually featured a leading female character successfully rising from Woolworth counter girl to musical star.

A worker’s productivity determines the wage they will be able to secure in the marketplace. Thus, a minimum wage restricts occupational opportunities to only those workers productive enough to earn the minimum wage. Workers who do not have the education and experience to earn the minimum wage are denied the opportunity to gain the relevant training, experience, and references on the job that are necessary to raise their future productivity and wages. Instead of helping low-skilled workers, minimum-wage advocates take away their best opportunity to get into the market in the first place.

ABOUT DANIEL J. SMITH

Dr. Daniel J. Smith is an assistant professor of economics at the Johnson Center at Troy University.

ABOUT ZAC THOMPSON

Zac Thompson is a senior economics major at Troy University.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] […]

Comments are closed.