The Good Thing About the Donald Sterling Incident by Michael Nolan

The NBA’s Los Angeles Clippers have become relevant for the first time in decades. They came to dominate the news, however, because their long-reviled owner’s stark racism finally handed a smoking gun to somebody. It figures that, just as they got a taste of the on-court success Donald Sterling never seemed all that concerned with bringing to them, he one-upped them off the court.

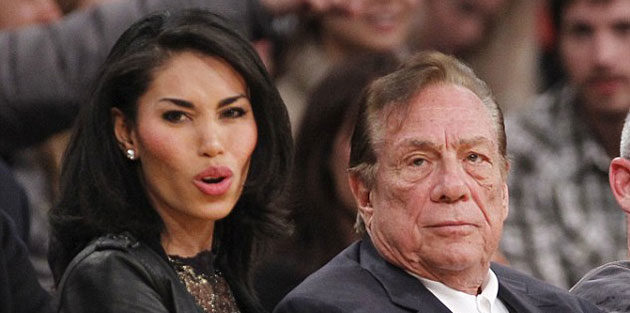

In case you don’t know, a tape of Sterling telling his girlfriend not to bring black people to his games or to advertise that she associates with them was leaked to TMZ last weekend.

This page will give you all the detail you want on the case. Or type “Sterling Clippers” into Google and buckle in.

Of course Sterling’s comments are despicable. They’re so blatant and blunt, I admit my first reaction was astonishment that anyone holding such racist thoughts would say them out loud. I thought they had to be fakes. But they didn’t leave any room for doubt.

Heck, I wondered how anyone could get up in arms about Magic Johnson. Magic Johnson? I’m from the land of Larry Bird (that’s “Larry Legend” to you) and I still love Magic.

Well, the tape wasn’t a fake. So this is one of the rare, cut-and-dried instances where it’s easy to call “racism.” There’s nothing else to call it. High-profile racial controversies are rarely so simply a matter of good guys/bad guys. That doesn’t stop people from coming out of the woodwork to portray them as such and, in the process, try to spread guilt far and wide.

So it’s kind of a relief that, in this case, there’s no real danger of that. There’s still a difficult question: How do you deal with a racist? It’s a lot more complicated than it sounds; front-office employees might have had a lot fewer options than the players. Sterling might have been little more than a tyrannical boss—everyone, sooner or later, has to learn to put up with one of those—about whom nasty rumors floated. Now they aren’t rumors.

The key is that now we can prove he acted on his racism. It wouldn’t be totally okay if he just harbored these feelings. But at least keeping them inside constrains action to some degree. That doesn’t apply here. This case is, if anything, actually encouraging.

Here’s why: Within hours, the people who do business with Sterling—starting with the players and coach who sell tickets and jerseys and stake him to a slice of the ever-more-lucrative broadcast rights pie—brought the full weight of their social power to bear against him.

Around here, we tend to like spontaneous action. Well, here it is.

The labor-vs.-management framework sportswriters like to apply to collective bargaining agreement (CBA) negotiations usually rings a little hollow. We’re not talking about miners asking not to be killed at work only to see Pinkerton agents set loose on them with clubs and guns.

But in this case, the labor side (well, the one that anyone notices, and the one with leverage) took control of the situation. Active and former players took their protests directly to the public—in interviews, via Twitter and other social media outlets—and made it clear they could and would inflict massive damage on the NBA if management got away with this behavior.

Even former players, like Michael Jordan and Magic Johnson (Jordan is part owner of another NBA team, Johnson part owner of baseball’s L.A. Dodgers)—two media-savvy guys if ever there were any—used their platforms to bring pressure. LeBron James took the gloves off, and he’s still playing.

Other owners also got into the act, only hedging a little about the authenticity of the tape—Sterling’s a litigious sort and likely to start filing lawsuits if there’s even a whiff of defamation.

Sponsors moved away as quickly as they could, too.

More to the point, the Clippers were set to boycott their Monday-night playoff game. Apparently all the other teams playing that night were ready also. I don’t know what U.S. labor laws—which tend to have a lot of strict, complex rules about strikes—would say about this. I don’t know if the players even cared about that. It doesn’t look like they did, and that’s how it should be.

Then, of course, NBA commissioner Adam Silver dropped the hammer. I didn’t know until this story broke that there was such a thing as an NBA Constitution; apparently it’s a secret document only the owners get to see. But it does allow them to force an owner out of the league.

I’m among those who’d like to see racism completely eradicated from human society. I doubt that’s a realistic goal, but then neither is permanent peace, justice, and prosperity, and yet I still want those things.

But the approach to that eradication is everything. Consider some extreme scenarios: If mind-control chips could be installed in every potential bigot, the monetary costs would amount to nothing next to all the others (social, psychological, you name it). A couple steps back from that extreme, maybe allowing the State to execute, immediately, anyone who could be shown to have the “wrong” opinions (bigotry, homophobia, violent religious extremism, approval of the New England Patriots) would at least make everyone clam up about it. But then the fights over who got to be in charge would be even more vicious and divisive than U.S. politics are already. You think arguments over school curricula or who gets to say what a marriage is are nasty?

I don’t think outcomes such as these are very likely, and I doubt anyone else does, either. But informal mechanisms of imposing costs on these kinds of attitudes tend to get short shrift. After all, if there’s a controversy big enough to break out of the sports pages, politicians are going to get a whiff of it and elbow their way to the front of the pack in responding to it.

I’m aware that a politician was involved here; the players turned to former NBA player and current Sacramento Mayor Kevin Johnson for some advice and leadership. That’s a far different scenario. Johnson, after all, was a former player. And he has a lot more experience in crisis management, negotiation, leadership, and a host of other skills than NBA players—who’ve spend most of their lives honing their playing abilities and anyway still have work to do—are likely to have.

Maybe someone would want to mount some kind of First Amendment argument here. But that’s bogus: The NBA’s relationship to the State is, like that of every other sports league in the United States, pretty murky and distasteful. It still remains a private organization. Private organizations should get a very wide berth to choose the people with whom they’ll do business, and who gets let in. That should include giving the boot to a guy this far beyond the pale. Those fleeing sponsors? Well, they were exercising their First Amendment rights, too.

But the point is, this isn’t an issue of the State punishing or restricting anyone’s speech. The First Amendment protects people who object as much as it does people saying objectionable things. The only meaningful constraints there have to do with matters of civility and etiquette—which the league values—and Sterling had already placed himself well outside of that kind of consideration.

I know there are people who are frustrated—at the very least—that when Sterling sells, he’s going to make a huge profit on the purchase, aside from whatever he’s pocketed since he bought the team in 1982. I’d bet there are plenty of people who want the team simply taken from him, along with the $2.5 million fine.

And it’s galling that he’s still going to be rich—and probably still a cro-magnon bigot—after all of this shakes out. It’s galling whenever lousy people get rich. This is why it was so easy to pass off the narrative that 2008 was only about Wall Street sleazeballs, and why, even though I don’t buy that narrative, I don’t sympathize with those Wall Street sleazeballs. It takes an effort to remind myself that “Wall Street” and “sleazeballs” aren’t actually 100 percent synonymous. That’s bias on my part.

The NBA can’t address the infuriating fact that bad people prosper sometimes. But the important point is that they shouldn’t. Because rules matter, and the more freedom people have to draw up the rules by which they’ll associate, the more flexibility societies have to address both desires and problems on whatever scale they occur. On the one hand, this is why it’s good to be able to move to another state if you don’t like the regime in your current one. On the other, it’s why the feds are maybe the worst people to, say, weigh in on the proper interpretation of the bylaws of a local Masonic Lodge.

It’s reassuring that the NBA has rules in place that do not restrain it from doing something in a case like this. And, as bad a name as profit has, it’s also doing its backstopping work: If the rules hadn’t allowed the NBA to address this situation this way, well, the players could have hit the owners and the league right where it hurts and walked off the court. There’s no telling if they would have been able to recoup any losses they might have incurred that way. I’m not clear what the rules are on that point. But kudos to every player willing to go to the wall about that; I’d bet they didn’t spend a ton of time reading bylaws and contract clauses, and that’s as it should be.

As a final note, I thought Mark Cuban, the owner of the Dallas Mavericks, showed a lot of guts. I can see why people in the league (and fans of the rival San Antonio Spurs and Houston Rockets) might find the guy obnoxious, and I don’t know enough about him to give him any sort of blanket endorsement. But I do like his willingness to go out in public and poke the NBA (and the NFL, even, which I think was recently granted its own SWAT team) when he thinks something stinks. He doesn’t seem intimidated by the imperious, authoritarian air that pro sports league offices tend to cultivate.

But he aired a concern that, in its complexity, is probably familiar to every libertarian who’s ever so much as thought about states’ rights and had to confront the very real likelihood that, in response, people will accuse him of being pro-slavery and worse. Here’s his statement:

“What Donald said was wrong. It was abhorrent,” Cuban said. “There’s no place for racism in the NBA, any business I’m associated with. But at the same time, that’s a decision I make. I think you’ve got to be very, very careful when you start making blanket statements about what people say and think, as opposed to what they do. It’s a very, very slippery slope.”

There’s always a danger—and it’s heightened in a case like this one, where the person in question was so blatantly, despicably clear about it—in letting the emotional reaction carry the day and calling for someone’s head. I can imagine someone wanting that literally to be taken from Sterling. I can’t blame them. And I don’t see any problem at all with emotions getting involved here. But Cuban’s exactly the sort of guy who, if the NBA is given blanket permission to punish at will for whatever they don’t like about an owner, would be . . . well, he’d still be doing other stuff, a lot of which at least sounds cool. But he’d be kicked out of the league faster than you can say “Mavericks’ maverick owner.”

So I give him credit here for making this point, even at the risk of some opportunist jumping on his statement as evidence that he doesn’t really hate racism—and therefore is probably a racist himself. Or that he actually defended Sterling, which . . . well, go reread that quote.

But he makes a point about rules and the importance of people being able to form and change them in private groups, and hopefully to serve all members of those groups. I hope this topic comes up more in the following weeks, as the NBA maneuvers to rid itself of Sterling and avoid an avalanche of lawsuits.

But for now, this story is the main headline (warning: Maybe Not Safe for Work). And the secondary header is that nobody was just going to submit to whatever solution their “leaders” or our rulers came up with.

Utterly eliminating racism—like, even in its faintest shades, from the innermost hearts of everyone—isn’t easy; it might not be possible. But bigotry can be made a lot more expensive. Too expensive, even, for a guy who hands out Bentleys like other people bum cigarettes.

ABOUT MICHAEL NOLAN

Michael Nolan is the managing editor of The Freeman.

RELATED STORIES:

Sterling Surrenders Control of Clippers To Wife…

Mark Cuban blasts critics: ‘A racist I am not’…