Fidel Castro’s Testament by Brian Latell

Oddly, there is no mention in the letter of the release of the three convicted Cuban intelligence agents from American penitentiaries. The key figures of the large Cuban spy ring that operated in the United States had been heralded as national heroes by Fidel before his retirement. He was extravagantly associated with the protracted campaign to win their release. The regime’s propaganda and intelligence machines labored long and diligently, overtly and covertly. But Fidel has not taken a victory bow now that they are home.

Rumors of Fidel Castro’s precarious health may swirl again in the aftermath of a letter issued over his signature earlier this week. Addressed to the Federation of University Students, the retired leader is quoted briefly about the changing Cuban relationship with the United States.

After remaining silent for more than five weeks following the announcements by President Obama and Raul Castro of measures taken in pursuit of détente, Fidel finally weighed in. “I will explain,” he is quoted saying, “in a few words, my essential position.”

Ghost written or not, his message provides a hedged endorsement of the process, though not of any of the steps taken by either side to normalize relations. He says nothing, for example, about the impending restoration of diplomatic relations that he caused to be broken in January 1961.

Nowhere in the message does Castro express unambiguous approval for detente. Perhaps the nearest he comes is by stating that he does not reject a “peaceful solution to conflicts or threats of war.” Employing similar lofty language, the letter merely states.

- “Defending peace is the duty of all.”

- “Any negotiated, peaceful solution . . . which does not imply the use of force must be addressed in accordance with international principles and norms.”

- “We will always defend cooperation and friendship with all the world’s peoples, and with those of our political adversaries.”

In short, the message can only be read as grudging. Castro is quoted saying, “I do not trust the policy of the United States, nor have I exchanged one word with them.” It recalls his militance and intransigence during decades of dealings with ten American presidents: “revolutionary ideas must always be on guard. . . . In this spirit I have struggled, and will continue to struggle until my last breath.”

All this sounds reliably like Fidel. But the odds are good that he did not actually contribute meaningfully to the drafting of the document. It is impossible to know of course, but it reads more like a skillful brief composed by Raul Castro’s designees.

They wanted Fidel’s stamp of approval for moving toward better relations with the United States. Emblazoned on the front pages of the major Cuban dailies, the letter got maximum exposure on the island.

After Fidel’s long silence it was also necessary for the regime to stifle speculation that he had died or was on his deathbed. And, for many, his extended silence left the impression that he was opposed to normalization with Washington. It was unacceptable for either of those impressions to persist.

Yet, no utterance attributed to Fidel would have been credible had he enthusiastically endorsed rapprochement. Since his university days –as he in fact mentions in the letter — he pursued radical, anti-American ideals. For him now, in his late eighties, suddenly to abandon decades of anti-American intransigence would not have made sense. After all, the American economic embargo remains fully in force. Other historic Cuban demands are also still unassuaged. How could he give unequivocal approval to a process still in its early stages?

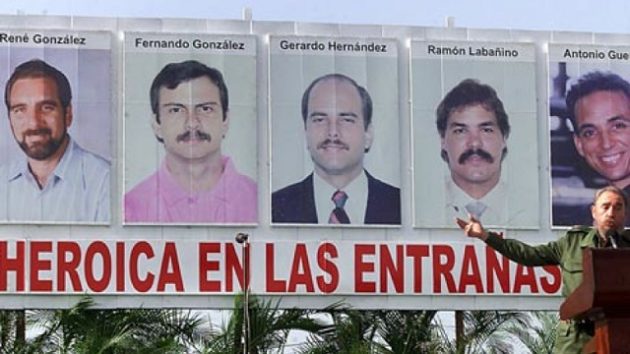

Oddly, there is no mention in the letter of the release of the three convicted Cuban intelligence agents from American penitentiaries, or of the America contractor who served five years in a Cuban jail. The key figures of the large Cuban spy ring that operated in the United States had been heralded as national heroes by Fidel before his retirement. He was extravagantly associated with the protracted campaign to win their release. The regime’s propaganda and intelligence machines labored long and diligently, overtly and covertly. But Fidel has not taken a victory bow now that they are home.

Nor has he met with them as they are being lionized in the official media as representatives of a new generation of revolutionary heroes. If he is not on his death bed, or severely impaired, a photo op with them would have been a routine event. Other than for reasons of health, therefore, it seems inexplicable that he has failed to boast of the Cuban success in bringing them home.

Two days after the letter was aired in Cuba, the press reported that Fidel had met with his old friend and biographer, Brazilian friar Frei Betto. They engaged, it was reported, in a friendly conversation about national and international issues. Normally under such circumstances, a photo of the two would have accompanied the article.

But this time, the photo of them attached to the story was acknowledged to have been taken in February 2014 during an earlier meeting. The most recent photos of Fidel appeared in the middle of last year and he has made no public appearance in about a year. Will rumors of his imminent demise be stoked anew?

Brian Latell, Ph.D., is a distinguished Cuba analyst and a Senior Research Associate at the Institute for Cuban and Cuban American Studies at the University of Miami. He has informed American and foreign presidents, cabinet members, and legislators about Cuba and Fidel Castro in a number of capacities. He served in the early 1990s as National Intelligence Officer for Latin America at the Central Intelligence Agency and taught at Georgetown University for a quarter century. Dr. Latell has written, lectured, and consulted extensively. He is the author of After Fidel: The Inside Story of Castro’s Regime and Cuba’s Next Leader and Castro’s Secrets: The CIA and Cuba’s Intelligence Machine. Brian Latell is a contributor to SFPPR News & Analysis.