5 Reasons Serious TV Debates Are Impossible by David & Daniel Bier

If you’re looking for a sober intellectual dialogue on the state of American public policy, don’t watch presidential debates.

They repudiate every requirement for such a discussion. They remove serious ethical questions from their philosophical foundations and offer answers fit only for bumper stickers and thirty second soundbites. They teach us one lesson: that no economic or moral issue is too important or complex to be solved with a slogan — hocus pocus campaign cure-alls for every social ill.

The blame lies partly with a political class devoid of substance, but it is impossible to ignore the forum in which the country has chosen to discuss the fate of its government.

“The medium is the message,” Marshall McLuhan asserted in his 1964 book Understanding Media. McLuhan overstated his case, but it is true that certain media lend themselves to some kinds of messages more readily than others. And, much like trying to send a sonnet via smoke signals, television’s form precludes certain content.

The kind of message that TV transmits most easily is entertainment. There’s nothing wrong with entertainment, but it is not a substitute for sober, rational analysis. The medium of television imposes almost insurmountable constraints on thoughtful conversation, and that’s why even if candidates with serious ideas were allowed into the debate, it would do little to help them.

Serious TV debates are impossible for at least five reasons:

1. Television is entertainment.

Almost by definition, television is not serious — it’s entertainment. It is where the vast majority of people go to turn off their brains and relax. If you invite friends over to watch the debate, I’m sure you won’t forget the chips and beer.

The TV debate setting invites citizens to join the challengers for America’s highest political office at a location that is the political equivalent of a circus, a movie theater, a ballpark, a clown show, a strip club, or a porn studio, because the location — your television set — is the same location as all these other diversions.

Even worse, it is as if they are all going on simultaneously in other rooms. Upset your audience — talk about children being burned alive by U.S. bombs overseas — and the burlesque is always just one click away.

Everything about television debates screams diversion, not rational discussion. Commercials reduce any candidate to the level of a Cialis ad, minus the disclaimers. The flashy promo and the upbeat intro-music transform political discourse into reality TV. Its not-so-subtle message is, “This is going to be fun!”

TV’s demand is that debaters be more amusing, not more intellectual. It’s why CNN runs stories on “Hollywood Debate Advice.” What does Hollywood know about public policy? Nothing, but in the age of TV, “politics is show business,” as Ronald Reagan put it.

Reagan was not only right — he excelled at it. After his 1984 debate with Walter Mondale, a single joke by Reagan about his age was replayed over and over again in post-debate coverage. Even today, that joke lives on as the most successful debate moment ever.

2. Television is about image.

Books — the media of lengthy, intelligent discourse — have substance: words, sentences, paragraphs, chapters, which form propositions about the world. They have meaning that takes real intellectual effort to grasp.

By contrast, images appeal to our eyes, not our minds. Images lack propositional content, so they can be viewed without any mental effort. Their appeal is mainly emotional (fast moving = exciting). The appeal of constant visual stimulation is why Michael Bay kept the average length of any shot inTransformers to about 1 second. People are absorbing views on the candidates (“Trump looks more presidential”) that have no intellectual content whatsoever. They might as well be choosing new drapes.

As Michael Shermer explains in Scientific American, when voters are given the choice between an educated, experienced, and ideologically-aligned candidate and a good-looking one, they overwhelming choose looks. Famously, Nixon won the first televised debate with John F. Kennedy among radio listeners, but lost it among television viewers — lighting and makeup might have changed history.

Dozens of academic papers have been published on how TV viewers can believe they are learning material while they watch, but can’t correctly answer even basic questions about the show’s content (see here, here, and here).

Because books force people to think and create abstract ideas from concrete shapes, readers do much better at holding information. TV debates create the illusion of informing the public, but as many talk shows and opinion polls demonstrate, most Americans lack even elementary information about the candidates — and the political system they are running in.

To most Americans, Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump are two faces, not two sets of ideas, and the content of their speeches reflects that reality. Rand Paul and Carly Fiorina are just two less “presidential” faces, and they get less “face-time” on cable news.

In print, there are no faces: there is only idea-time.

3. Television precludes lengthy exposition.

Any candidate that refuses to dutifully repeat conventional beliefs faces an insurmountable hurtle: time constraints.

“The beauty of concision — saying a couple of sentences between two commercials — is that you can only repeat conventional thoughts,” notes linguist Noam Chomsky. “Suppose you say anything the least bit controversial. People will quite reasonably expect to know what you mean… If you say that, you better have some evidence. In fact, you better have a lot of evidence because that’s a pretty startling comment. But you can’t give evidence if you’re stuck with concision.”

In a TV debate, anything that requires more than two minutes to explain will never be explained. This makes debates ripe ground for platitudes about “cutting red tape,” “eliminating waste,” “investing in America,” and “fixing the tax code.”

Anything complicated or controversial — a serious conversation about the causes of terrorism, for example, or the adverse consequences of drug prohibition — is out of the question. They hate America, bomb their countries; drugs are evil, save the children. Now for words from our sponsors.

Almost as bad for libertarians, concision presupposes every problem can be solved not just in two minutes, but in two minutes by the president. Before Rand Paul finishes explaining why it’s not the president’s job to create jobs, his time is up.

The workings of voluntary society never figure very prominently in presidential debates, because every single social problem, real or imagined, is being posed to a politician. One can’t simply say, “the president can’t do anything about recessions” or “curing drug addiction isn’t my job” — the presumption is, it is your job, since you’re here and we’re asking you.

4. Television forbids complexity.

Debate success leaves no viewer behind. Complexity is banned, not just because of time constraints, but because the TV waits for no one. There is no time for pondering or digesting. The rip tide of sounds and images drags you along.

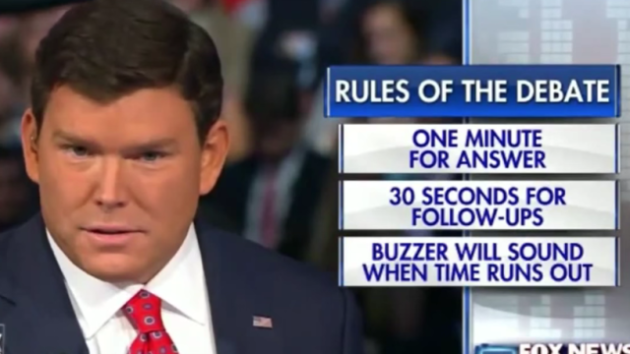

The first 2016 debate allowed 60 seconds for candidates’ answers, but, even if it had given them 5 minutes, it still allowed zero seconds for audiences to think about them before the next soundbite — and so that is the maximum amount of thought candidates can require of viewers.

Successful candidates make sure to require nothing of viewers because a viewer who is confused will change the channel or miss the punch line. A person lost in thought ceases to watch, which is the whole point of TV.

Knowledge of history is irrelevant on TV — the only thing that matters is now. Books are written in past tense: history is their domain. TV is made in the present — who cares what led to 9/11 or the recession or the rise of ISIS: what will you do now?

Neil Postman writes in Amusing Ourselves to Death that after “be entertaining,” TV’s central commandments are “thou shalt have no prerequisites, no perplexity, and no exposition.”

Nothing should go over the head of a single potential voter, so preach to the lowest common denominator. You can’t expect your viewer to bring any prior knowledge of issues with them — and you can’t provide them with any — so just appeal to common emotions and conventional wisdom.

It’s no wonder typical debate transcripts read on a sixth grade level. Matt Welch says of the current Republican front-runner, “Trump’s real adversary is the full-length transcript. These aren’t speeches, they’re seizures.”

And audiences love them.

5. Television is anti-intellectual.

Television forbids complexity and exposition, and it exalts entertainment and image. It is, in other words, a fundamentally anti-intellectual medium. It communicates emotions, not ideas.

Consider the most famous moment from the Bill Clinton-H.W. Bush debates. During the “town hall” debate, a woman asked a barely coherent question about how the national debt personally affected the candidates.

Bush launched into a discussion of interest rates, only to be interrupted, and told to “make it personal.” He responds defensively and staggers through his answer. But Clinton understands his medium, and rather than answering, simply says, “Tell me how it has affected you.”

That’s what a debate is really about: us. Just as commercials aren’t really about products, but about the desires of their consumers (“beer will make you attractive to women,” “shampoo will make you sexy,” “Rogaine will get you a promotion”), so too are debates about candidates emotionally connecting with voters: reassurance, not uncertainty; strength, not weakness; understanding, not disinterest; warmth, not distance.

“Mitt Romney still has an empathy or connection gap,” explained CNN’s John King in 2012. An empathy gap? In this world, truth is an afterthought, the job of nit-picky “fact-checkers.”

Debates aren’t about the truth, they’re about verbal reassurance — in the moment, with a calm look and a steady voice. Rationality has no part in this world.

A version of this piece was first published in 2012 and is unfortunately still relevant.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!