Connecting the Dots: How the Latest Affordable Housing Policy Benefits Homeowners and Realtors, not First-time Buyers

Tobias Peter, senior research analyst at the AEI Center on Housing Markets and Finance, wrote the following blog post: Connecting the Dots: How the Latest Affordable Housing Policy Benefits Homeowners and Realtors, not First-time Buyers.

In it he explains how “another government housing policy intended to open “the door to home purchase mortgages for large numbers of new buyers” has failed. Instead of bringing income-constrained borrowers into the market, it making housing less affordable by adding more fuel to a national house price boom that is pricing them out of the market, while providing a windfall to home sellers and real estate agents.”

Connecting the Dots: How the Latest Affordable Housing Policy Benefits Homeowners and Realtors, not First-time Buyers

Tobias Peter (Tobias.Peter@AEI.org), Senior Research Analyst

AEI’s Center on Housing Markets and Finance

January 16, 2018

The numbers are in and yet another government housing policy intended to open “the door to home purchase mortgages for large numbers of new buyers” has failed. Instead of bringing income-constrained borrowers into the market, it is making housing less affordable by adding more fuel to a national house price boom that is pricing them out of the market, while providing a windfall to home sellers and real estate agents.

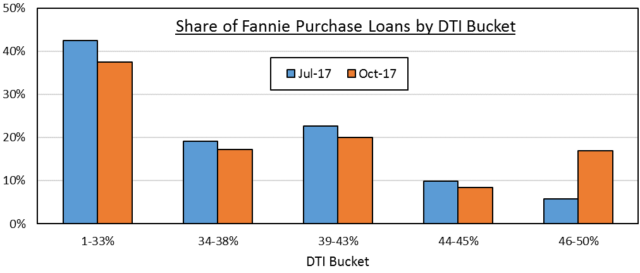

Let’s connect the dots. As of the weekend of July 29, 2017, Fannie Mae, one of the two government sponsored housing enterprises (GSE), started buying and securitizing many more mortgages with a debt-to-income ratio (DTI) of up to 50 percent. The DTI measures the ratio of monthly payments to income. The higher the ratio, the greater a borrower’s monthly debt payments and the greater a borrower’s likelihood to default.

Prior to the policy change, the large majority of Fannie borrowers were limited to a DTI of 45 percent, with only a few borrowers allowed to go as high as 50 percent with compensating factors such as a certain number of months of cash reserves or a higher down payment. Fannie’s move thereby allowed borrowers to take on more debt relative to their income. Freddie Mac, the other GSE, had been buying more mortgages with DTIs over 45 percent than Fannie, but it too ramped up its purchases after Fannie’s announcement as data from the AEI National Mortgage Risk Index (NMRI) show.

Sensing an opening for income-constrained borrowers to now enter the housing market, housing advocates hailed Fannie’s move as a “win for expanding access to credit.” Yet this line of reasoning was always flawed. Access for income-constrained borrowers already existed. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA), another government housing entity, already guarantees loans with a DTI up to 57 percent and with less stringent credit score and down payment requirements than Fannie or Freddie ever would. By offering this service at a lower cost to certain borrowers, Fannie’s (and Freddie’s) move thereby pitted one government guaranteed insurer of mortgages against another.

The effect of the change has been stunning since it took effect. First, the share of Fannie borrowers with a DTI above 45 jumped 11 percentage points to 17 percent within just three months after the program’s implementation. Yet precious few of these borrowers were new market entrants while the large majority were Fannie borrowers taking on more debt.

This is problematic. In today’s seller’s market, prices have been rising rapidly. The measures from a variety of sources all show prices rising 6 to 7 percent over the past year, and as much as 10 percent for entry-level homes. DTIs function as a friction slowing the increase of house prices through binding limits. Remove the friction and house price increases will pick up. This happens the following way: First, income-constrained borrowers take advantage of the higher limits, as they initially no longer have to settle for lower priced homes. Then, because supply is limited, the extra debt ends up raising prices – either directly through more aggressive bidding for houses or indirectly through appraisals when inflated home sales become comparables for other sales as our research shows. Soon, the cycle feeds on itself and everyone, not just income-constrained borrowers, has to take on more debt. This is exactly what happened as the NMRI data also show (see chart).

What is driving up prices so rapidly today is the combination of a seller’s market, which is now in its 63rd month, and more liberal access to credit through, for example higher DTI limits, or generally looser lending standards as documented by the NMRI. Since 2012, national house prices have risen by around 50 percent as shown by the Case-Shiller index, but in the bottom tier of the market, where supply is more constrained and credit more liberal, prices have doubled.

And so, what started as a policy change by Fannie Mae to close the growing affordability gap has added yet more fuel to the house price boom, especially at the lower end of the market. Thereby this policy will benefit existing homeowners, realtors, and builders, but it will hurt first-time buyers and those with limited resources as they will have to stretch further to afford homeownership or be forced to remain on the sidelines.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!