The Persistence of God

For many centuries, almost everybody in the Western world – the world that used to be called Christendom – was a Christian believer. Then, a few centuries ago, some people (mostly intellectuals) began drifting away from Christian belief. But they found that they couldn’t utterly renounce their old Christian beliefs. They were convinced that Christianity was a mere tissue of superstition, and there was nothing they hated more than superstition. Yet they couldn’t get rid of their belief in some essential elements of this old “superstition.” No matter how much they tried to clear their minds of old superstitions, some of them persisted.

Deists, for example, whose heyday was the 18th century, ceased to believe that Jesus is divine or that God is a Trinity. But they continued to believe in an afterlife, and that God exists and that he rewards the good and punishes the wicked. Though the divinity of Christ was a “superstition,” and the Trinity was a “superstition,” somehow Deists felt that belief in God was not a superstition. That was a true belief, just as rational as Newton’s theory of universal gravitation.

In subsequent generations, many went further in their rejection of Christianity. Some turned to pantheism, a belief that flourished among romantics in the first half of the 19thcentury. They rejected an idea of God that the Deists had retained, namely that God is personal. But they continued to believe in God, an impersonal God that was either identical with nature or at least permeated and controlled nature. In the United States, the finest flower of pantheism was to be found in the works of Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Then came the atheists, who were determined to get rid of God completely, whether this God be personal or impersonal. Karl Marx, a resolute metaphysical materialist, was the most famous example of this species of anti-Christian. But even Marx didn’t get rid of God completely. Of course, he got rid of the name “God,” but he continued to believe that there was a great and ultimately benevolent power that would bring the human race to a condition of happiness, not a post-mortem happiness, but happiness in this very world of time and space.

The totally unspiritual and unthinking matter that (in Marx’s view) lies at the foundation of all reality is not, and never has been, indifferent to human happiness. All this time, all these countless centuries, the universe has been moving in the direction of a worldwide human society that will be classless, and as a result of this classlessness will be prosperous and free and boundlessly creative. And we moderns are now, in that rosy vision, not far from this glorious consummation.

Matthew Arnold, a better poet and critic than he was a Christian theologian, in his attempt to reduce the idea of God to its bare essentials, defined God as “an eternal not-ourselves that makes for righteousness.” The “God” of Marx may be defined as an eternal not-ourselves that makes for a classless society.

As long as we believe that there exists, or should exist, some great power beyond our individual selves that can bring humans to happiness, we have not fully gotten rid of the Christian idea of God. After many centuries of Christianity, the belief that there is, or must be, such a power is built, so to speak, into the structure of the Western mind.

If you have grown up in the midst of Western civilization, if you have absorbed the preconceptions of that civilization with your mother’s milk, you will find it almost impossible not to believe in the existence of that great and benevolent power. If you are unable to believe that this great power takes the form of the Christian God or the deistic God or a pantheistic God or the “God” of historical materialism, you will believe that it takes some other form. It will be very difficult, if not impossible, for you honestly to believe that no such power exists or can exist.

Nowadays, I submit, at least among those who are unable to believe in the God of the Bible, the most common form of the belief in a great and benevolent power is belief in an omnicompetent government. If you’re an atheist and you find that you’re unable to believe in the God of the Bible or the God of Deism or even the God of pantheism, and you’ve given up on the “God” of Marxism, it is probable that you will believe that there is no social problem – poverty, bad neighborhoods, crime, violence, racism, sexism, homophobia, Islamophobia, xenophobia, traffic jams, bad breath in dogs, lack of education, ill health, mental illness, loneliness, marital unhappiness, etc. – that cannot be solved by government, at least given enough time and, of course, money.

The most striking example of this confidence that a godlike government can solve our problems is the expectation that the governments of the world, operating (as it seemed during the Obama presidency) under the leadership of the USA, can shape the world’s climate over the next century or two, and can do this in a benign way. (I say this, by the way, without meaning to take a position on climate-change theory.)

Further, the godlike government in question is the U.S. federal government, not state and local governments, which clearly lack godlike capacities; and not the governments of small countries. Ideally, the best government to take care of these things would be a world government. But we are probably centuries, at least, away from that. In the meantime, the U.S. federal government, being the richest and most powerful of all the governments in the world, is the best we can do.

I am contending, then, that there is an affinity, at least in our post-Christian age, between atheism and a belief in super-big government. The more you incline to the former, the more you will also incline to the latter. And the more you will tend to ignore the – quite abundant – evidence to the contrary.

![]()

David Carlin

David Carlin is professor of sociology and philosophy at the Community College of Rhode Island, and the author of The Decline and Fall of the Catholic Church in America.

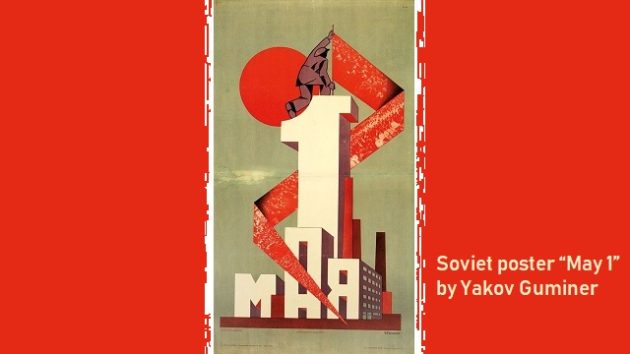

EDITORS NOTE: The featured image is of a Soviet poster (“May 1”) by Yakov Guminer, 1928. © 2018 The Catholic Thing. All rights reserved. For reprint rights, write to: info@frinstitute.org. The Catholic Thing is a forum for intelligent Catholic commentary. Opinions expressed by writers are solely their own.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!