There Is No Secular Culture

James Matthew Wilson: To encounter Christ and to abide with him is not just the Good News, it is the only news that stays news, forever.

Simon During has made a dismaying but perceptive argument about the relationship between religion and culture in, of all places, The Chronicle of Higher Education, the flagship of today’s academic world. The secularization of the modern West involved not the abandonment of religion, but its reduction to an optional dimension of human life (an idea borrowed from Charles Taylor’s important book, A Secular Age). The demotion of religion led to a promotion of culture. Culture in the modern age became a new god-term to give coherence to civilization and society – a kind of immanent substitute for the transcendence of Christian faith. As Matthew Arnold contended, culture would save us from anarchy.

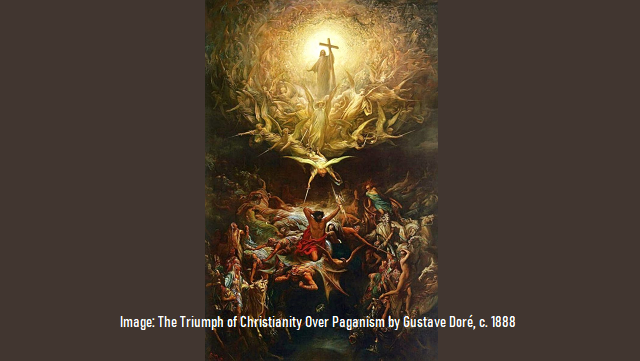

This substitution is now being undone, During argues, by a second secularization. Just as the authority of the Church was eroded by various events that converged on a secular political order, so now, a series of events, from neoliberalism to feminism to identity politics, has led to a rejection of the canons of culture.

You don’t need any longer to have a certain appreciation for Bach’s St. Matthew Passion or Virgil’s Aeneid in order to be thought a decently civilized human being; such knowledge might actually be counted against you. Better to spend your time studying risk analysis or cybersecurity, say the neoliberal technocrats. Or postcolonial criticism of Virgil or, better still, leave that dead man behind for the lyrical stylings of some feminine vicar of a non-Western people, or an advocate of the “pedagogy of the oppressed.”

The history During offers may not proceed according to iron laws, but it does have its own momentum that would be hard to counteract, even if you don’t much like it. I’d like merely to consider the linkage he sees between religious and cultural secularizations, to raise some doubt about the very idea of culture serving as a “substitute” for religion, and to suggest that great works of culture are powerful expressions of the truth of Christianity.

Early twentieth-century Christian writers, from Henri Massis and Charles Péguy to T.S. Eliot and Christopher Dawson, often seemed to slide between defenses of Christianity and of culture, under that nebulous term, the West – for good reason. They perceived rightly that Christianity transcends every historical reality, including the culture of the West, and yet they also saw that it would be hard, if not impossible, to have one without the other.

They saw this because, in a very particular way, it is true. We owe to the best pagan philosophers the most compelling and finely articulated description of what it means to be human. Human beings are creatures whose souls by nature desire to know the truth for its own sake; creatures who not only desire the truth but need to contemplate it. We are thus fulfilled, made happy, and find our lives transformed, from the vain pursuit of worldly glory to a resting in the eternal glory of all that is, of Being Itself.

This was, in a manner of speaking, a hard-won cultural insight, but it was more fundamentally a religious one. God’s revelation to Israel and his sending of his Son into the world to proclaim the Gospel brought the world to its predestined fullness of understanding. We are fulfilled by contemplation of truth, because the Truth is a person who made us to know him and to love him. To encounter him and to abide with him is not just good news, it is the only news that stays news, forever.

The modern age that During and Taylor describe as secular never fully abandoned these insights, though it truncated them and deprived them of their purpose. It recognized something distinctive and mysterious about human persons: We are made for transcendence. The modern age simply stopped stating what kind of transcendence and, in the process, clouded its own vision.

Yes, we have souls, moderns affirm: we do rise above our material existences, at least from time to time, in an act of self-consciousness. The works of high culture are just what they sound like –from the philosophy of Kant and the painting of Friedrich, to the opera of Wagner or the poetry of Rilke. They remind the forgetful soul that it may rise above, however briefly, nature’s mechanical laws.

Alas, modern culture could affirm this elevation, this ecstasy, but only with a kind of pathos. We have moments of illumination and then sink once more into the flesh. “To toll me back from thee [eternal spirit] to my sole self,” as Keats wrote. People kind of caught on to the gimmick after a while. Why bother with a pointless species of transcendence? It seems much too ethereal in comparison with that more functional transcendence of money, by which we secure for ourselves a miniature immortality. Conversely, cultural elevation seems narcissistic indulgence compared with the transcendence of pursuing political goods that may survive us.

One secularization necessarily follows from the other. The foundation of culture, as Joseph Pieper frequently argued, is the cultus – the cult. Without a clear sense of our ordination to the contemplation of God, all the works of man that seem true, good, and beautiful come to appear, first, as mere distraction, and finally, as deception.

In The Person and the Common Good, Jacques Maritain argues that to be a human person is to be a creature ordered to immediate communion with God, but that personhood also displays a tendency to communion with other beings as well. The treasury of culture, as he calls it, is simply the irradiation of truth and beauty produced by our natural tendency to join ourselves to God and to others as persons.

If the Truth were not a person whom we encounter, there would be no primordial experience of which culture is a kind of wayward fruit: No human ordination to the sacred, no self-expression in the “secular” order. Conversely, all our encounters with works of culture are hints, reflections, echoes, regarding the nature and destiny of man. Listen to them.

COLUMN BY

James Matthew Wilson

James Matthew Wilson has published eight books, including, most recently, The Hanging God (Angelico) and The Vision of the Soul: Truth, Goodness, and Beauty in the Western Tradition (CUA). An associate professor of religion and literature in the Department of Humanities and Augustinian Traditions, at Villanova University, he also serves as poetry editor for Modern Age magazine and as series editor for Colosseum Books, from the Franciscan University at Steubenville Press. His Amazon page is here.

EDITORS NOTE: This Catholic Thing column is republished with permission. © All rights reserved.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!