Fossil Fuels and Fossilized Thinking

An expert in linguistics takes aim at the coloured language of the climate change debate.

Eighty-one years ago, in 1940, a popular science magazine published a short article by Benjamin Lee Worf that initiated one of the trendiest intellectual fads of the 20th century.

The author was a chemical engineer who worked for an insurance company and moonlighted as an anthropology lecturer at Yale University; the idea concerned the power of language over the mind and the claim that our mother tongue places restrictions on the things that we are able to think.

Whorf argued that Native American languages impose on their speakers a picture of reality that is totally different from ours, in such a way that their speakers would simply not be able to understand some of our most basic concepts, like the flow of time or the distinction between objects and actions.

Whorf’s theory led to a whole range of fanciful claims about the supposed power of language over thought, from the assertion that Native American languages give their speakers an intuitive understanding of Einstein’s concept of time as a fourth dimension, to the speculation that the nature of the Jewish religion was determined by the tense system of ancient Hebrew.

We now know that Whorf was mistaken in assuming that our mother tongue constrains our minds to the point of preventing us from being able to think certain thoughts. This would entail, for example, that if a language had no future tense, its speakers would not be able to grasp the notion of future time. But even in English we sometimes use the present tense to refer to the future, as in “They are arriving this evening.” Would a language that did this habitually prevent its speakers from having any grasp of the future at all?

Do English speakers who have never heard the German word Schadenfreude find it impossible to understand the concept of relishing in someone else’s misfortunes? More fundamentally, if the vocabulary of words in our language determined which concepts we were able to understand, how could we ever learn anything new?

How language channels our expression

In spite of these caveats, however, recent linguistic research has revealed that when we learn our mother tongue we do indeed acquire certain habits of thought that shape our experience in significant and often surprising ways.

Guy Deutscher’s 2010 book Through the Language Glass: Why the World Looks Different in Other Languages develops the renowned linguist Roman Jakobson’s insight that languages differ not so much in what they allow speakers to express but rather in what they oblige them to convey. Deutscher argues that this principle offers the key to understanding the real impact of the mother tongue on our thinking: if different languages influence our minds in different ways, this is not because of what our language allows us to think about, but rather because of what it habitually obliges us to think.

To illustrate this, he gives the example of someone saying in English “I spent yesterday evening with a neighbour.” As a hearer, you might wonder whether my companion was male or female, but you have no way of knowing that from what I said.

However, if we were speaking French or German, I wouldn’t have the possibility of equivocating in this way, because I would be obliged by the grammar of the language to choose between voisin or voisine, Nachbar or Nachbarin. French and German compel me to inform you about the sex of my companion whether I feel it is of any concern to you or not.

Language habits

I would like to develop a corollary of this principle going back to another article by Whorf entitled ‘The Relation of Habitual Thought and Behavior to Language’. In it he explores the ramifications of the impact on human behaviour of “language’s constant ways of arranging data and its most ordinary everyday analysis of phenomena,” based on the idea put forward by Whorf’s mentor Edward Sapir, an anthropology professor at Yale, that “the language habits of our community predispose certain choices of interpretation.”

In support of this idea, Whorf cites his experience as a fire insurance evaluator, in which he discovered that it was often not a physical situation per se, but rather the meaning of that situation to people that was the crucial factor in the start of a fire. Thus, for example, around a storage area for ‘gasoline drums’ great care will be exercised by people, whereas around a storage area for ‘empty gasoline drums’ behaviour may be different, with people sometimes smoking and tossing cigarette stubs around, even though ‘empty’ drums are more dangerous than full ones as they contain explosive vapour.

Whorf observed: “Physically the situation is hazardous, but the linguistic analysis according to regular analogy must employ the word empty, which inevitably suggests lack of hazard.”

The aura surrounding the adjective “fossil”

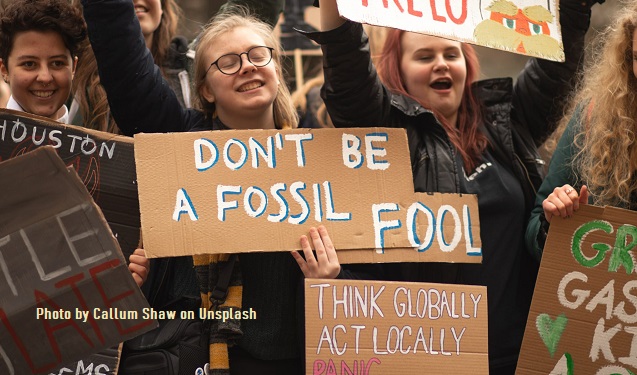

In the light of this principle, it is interesting to consider the customary use in contemporary discourse of the modifier fossil to describe hydrocarbon-based energy, as instantiated in these phrases gleaned from the international Greenpeace website: fossil fuels, fossil energy, fossil gas, fossil capital, fossil-free politics, fossil-free economy, fossil-free revolution.

Two of these expressions might not be self-explanatory: fossil gas is a way of referring to natural gas; fossil capital is “an economic system that prioritises never-ending growth over the welfare of people and the planet. This system plunders our planet’s resources while oppressing our most vulnerable. It perpetuates structural inequalities and deepens the climate crisis.”

The choice of this modifier for the noun fuel is anything but chance. As illustrated in the Google Ngram below, it became frequent around 1970 at the time of a conjunction of the rise of the environmental movement and media focus on the escalation of gasoline prices due to the OPEC decision to drastically cut down oil production:

Symbolically, the expression fossil fuels associates hydrocarbon energy with a number of underlying notions that present it in a highly unfavourable light. Not only are fossils dug out of the ground, which links them to dirt and mud (viz. the expression dirty energy), but they are also artefacts from a very remote past, which connotes the idea that hydrocarbons are utterly outdated and should be extinct like the species whose skeletons we display in museum exhibits.

And so it comes as no surprise to see the companies producing hydrocarbon energy portrayed as dinosaurs who must give way to the new generation of mammals in an article titled “The era of energy dinosaurs is coming to an end,” which maintains that “the big, slow-moving dinosaurs of the energy world face increasing competition from a swarm of smaller, fast-moving mammals.”

Habits of thought about carbon

It is perhaps salutary to realize that every time we use the phrase fossil fuels, we are entrenching a habit of thought that is beholden to a certain view of this type of energy. And so, even though this phrase slips smoothly off the tip of the tongue because of the alliteration of the initial labiodental fricatives, we should perhaps think twice before using it too casually.

The same thing goes for the phrase carbon footprint, in which an odorless and colourless gas is treated as a hard metal capable of leaving an indelible mark on the environment. Indeed, the reduction of the longer term carbon dioxide to the noun carbon in current discourse concerning energy is far from innocent. Not only does it present the purported environmental threat as a solid rather than a gas, but it also constitutes a concealed attack on the very foundation of life on the planet.

If one does an Internet search for “carbon is”, the top three suggestions proposed by the Google search engine are “carbon is the building block of life/carbon is the foundation of life/carbon is the basis of life,” amounting to a total of 907,000,000 hits on the web.

And indeed, the higher levels of CO2 in the atmosphere in the industrial era are making the earth greener and increasing crop yields: in its forecast of world cereal grain production for 2020/2021, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization foresees a 4.4 percent increase, up 2.6 percent from the record set in 2019/2020.

In 2016 a paper titled “The greening of the Earth and its drivers” was published in the journal Nature Climate Change by 32 authors from 24 institutions in eight countries that analysed satellite data and concluded that there had been a 14 percent increase in green vegetation over the previous 30 years, attributing 70 percent of this increase to the extra carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. The lead author of the study, Zaichun Zhu of Beijing University, says this was equivalent to adding a new continent of green vegetation twice the size of the mainland United States.

In the phrase carbon emissions, however, carbon is associated with a noun reserved for reference to pollution, thereby debasing the basis of life to the status of toxic waste.

If Sapir and Whorf are right that the language habits of our community predispose certain choices of interpretation, every time we hear or use such expressions, we are being conditioned to adopt a certain point of view on their referent. Caveat locutor et auditor!

COLUMN BY

Patrick Duffley

Patrick Duffley is Professor of English Linguistics at Université Laval, in Canada. More by Patrick Duffley

EDITORS NOTE: This MercatorNet column is republished with permission. ©All rights reserved.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!