Heroic beginning of Catholic Church in China

A humble Italian priest won tens of thousands of converts.

In 1905, one of the greatest Catholic missionaries to China wrote down his thoughts for the Chinese New Year. His story is still of interest today.

“It is Chinese New Year, and a new epoch has begun for China. It is now essential to activate every means to take advantage of this favorable time for our religion. If Europe were truly Catholic, I do not doubt that the time for China’s conversion would be now. But unfortunately one must look to the future with fear and trembling. There is no time to lose, and we should work tirelessly.”

These words, perhaps replacing “Catholic” with “Christian” due to the success of various brands of Protestantism in China, might have been written for the Chinese New Year of 2022.

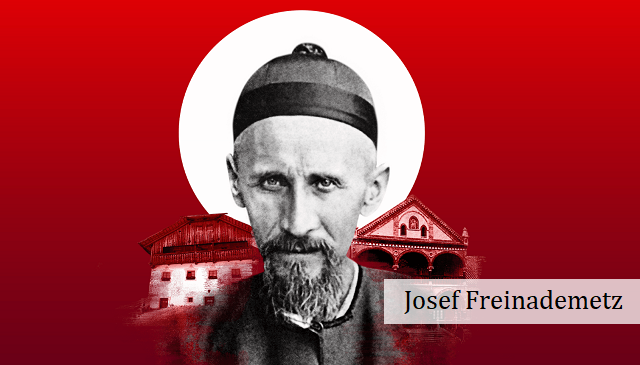

However, the text is not from 2022. It is from 1905. The person who wrote these wishes for the Chinese New Year was a mountain man from Val Badia, the Badia Valley, now part of the Italian South Tyrol, Josef Freinademetz. He had gone from being assistant parish priest in the mountain hamlet of St Martin to being a famous and successful missionary in China.

Add that he was a member of a linguistic minority that spoke Ladin (not a typo for “Latin,” but a Romance language spoken by less than 50,000 mountain villagers), and had learned Italian and German with great difficulty. He was the superior for the Chinese territory of a specialized religious congregation, the Verbites, i.e., the members of the missionary Society of the Divine Word.

Celebrating the Chinese New Year, he could state that he had become “Chinese with the Chinese,” speaking fluently three different Mandarin dialects and even wearing a pigtail. Pope John Paul II inscribed him in 2003 in the catalog of saints of the Catholic Church.

Several years ago, a visit to Val Badia led me to the poor birthplace of Freinademetz in the hamlet of Oies, a hamlet composed of half a dozen houses. Much more importantly, on August 5, 2008, Pope Benedict XVI visited the home, and prayed for China there.

In this remote corner of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (which became part of Italy after World War I), Ujöp Freinademetz (the German version, spelled Josef, of the Ladin name Ujöp would come only many years later) was born in 1852. The family lived in dignified poverty and in a typically Tyrolean Catholic piety, which may be difficult to understand today. The daily rhythms of prayer alternating with work were more reminiscent of a monastic community than a modern lay family.

It is not extraordinary that in this environment a religious vocation matured, and Ujöp, who spoke Ladin only, overcame the language barrier to enter the seminary of Brixen (now Bressanone, Italy) and become a priest. What was extraordinary was the dream that matured in the young Freinademetz, who had never traveled outside South Tyrol. He dreamed to convert the most populous country in the world, China, to Catholicism. Even though stories about the missions reached the seminary through Catholic magazines, Freinademetz knew precious little about China. But he understood it was immense and believed it should be converted.

From a local Catholic magazine, he learned of the existence in Steyl, in the Netherlands, of a new missionary institute that intended to devote itself to Asia, the Society of the Divine World, founded by a man Pope John Paul II will canonize along with Freinademetz himself, the German-Dutch priest Arnold Janssen. Freinademetz asked for and obtained permission from his bishop to leave the diocese and join the Verbites.

Janssen’s style was cold and severe, while Freinademetz was enthusiastic and exuberant. Also, Janssen had an academic education in secular universities and had been a professor, while Freinademetz had been barely able to complete the seminary with the greatest of efforts. Eventually, however, the two priests learned to understand and respect each other, and even became friends.

In 1879, the first two Verbite missionaries left for China: one was Freinademetz and the other was Johann Baptist Anzer. Later, Anzer became the first Verbite bishop in China, as Apostolic Administrator of Southern Shandong, then called Shantung. The position was offered to Freinademetz, but he refused out of humility, while keeping his role as superior of the Verbites in China.

Anzer was not the best choice for a bishop. He was authoritarian, troubled by personal problems of alcoholism, and concerned as a Bavarian to promote the political interests of Germany in China. When Anzer died in Rome in 1903, Freinademetz was again the most logical choice as bishop. This time, he might have accepted but was blocked by a veto of the German government, which was afraid that an Austro-Hungarian subject as a bishop might not continue to advance the political interests of Germany.

Freinademetz was, however allowed to serve as apostolic administrator of the diocese for several years. Finally, a German was nominated as bishop, Augustin Henninghaus. He proved to be a good bishop, and Freinademetz was happy to work with him. Later, Henninghaus became the first biographer of Freinademetz.

When Freinademetz arrived in China, his judgment on the local religions was very negative, and influenced by a Catholic literature he had read in Europe that certainly did not promote interreligious dialogue. He was impressed by what looked like miraculous feats of Buddhist and Taoist ascetics, but attributed them to the work of the Devil, although he added that some of them may be good men deceived by the Evil One without knowing it.

The men he regarded as criminal and bandits were the members of the anti-Christian secret societies, who had kidnapped and murdered several missionaries, and whose fury was unleashed in the Boxer Rebellion of 1899–1901.

Boxer-related atrocities were less prevalent in Shandong, where Freinademetz lived, but it was suggested to him to seek protection in one of the areas controlled by the Western armies. He refused, and survived the Boxer crisis unharmed, but not the subsequent epidemic of typhus. In fact, he insisted that he should visit the hospitals and even help the doctors and nurses, until he became infected himself.

He died in Daijiazhuang, Shandong, on January 28, 1908. While other missionaries had their bodies taken to Europe to be buried there, Freinademetz wrote in his will that “I love China and Chinese, and I want to be buried with them.”

His name was unpronounceable in China and he preferred to be called “Fu Shenfu,” the Priest Fu. Shortly before he died, Freinademetz wrote a report on his years of missionary activity in Shandong. When he arrived there, he found 158 Catholics in the region. Dying, he left 40,000.

It is a truism to state that Freinademetz was a man of his time, and we can regard some of his remarks about China and its traditions today as orientalist or colonialist. On the other hand, as Pope John Paul II noted when he canonized him, Freinademetz made a genuine effort to overcome his prejudices, eventually abandoning most of them, and understand the Chinese culture on its own terms.

His genuine love for the Chinese, Catholic or non-Catholic, was universally recognized. His grave was visited and honored by tens of thousands until it was desecrated and destroyed by the Cultural Revolution, although a memorial had been re-erected since.

Cultural problems aside, that a mountain man from a remote hamlet in the mountains of South Tyrol could not only conceive but begin to realize the idea of converting immense China, or at least a vast region of it, to Christianity remains an extraordinary story—one worth remembering on the celebration of Chinese New Year, with Bitter Winter’s best wishes to those who celebrate it.

This article has been republished with permission from Bitter Winter.

COLUMN BY

Massimo Introvigne

Massimo Introvigne is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new… More by Massimo Introvigne

EDITORS NOTE: This MercatorNet column is republished with permission. ©All rights reserved.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!