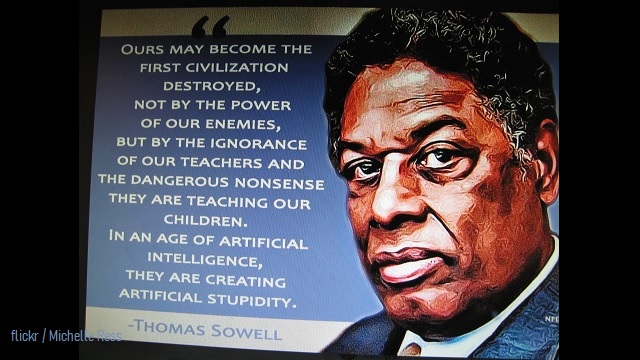

Is Thomas Sowell one of the most important thinkers of our time?

‘Maverick’ is an outstanding intellectual biography of this prolific African-American economist.

Fans of Thomas Sowell have been eagerly awaiting the new biography by Jason Riley, with the appetite being whetted by the release of Riley’s one hour documentary on Sowell’s life in January.

This is not a standard biography.

Apart from providing a basic overview of Sowell’s life (his difficult upbringing in the segregated South and in Harlem, his late entry into academic life and meteoric rise as a public commentator), the author’s primary goal is to provide an introduction to Sowell’s voluminous body of work on matters as diverse as economics, education, cultural disparities and political ideology.

Like Sowell, Riley is a conservative African-American writer. A member of The Wall Street Journal editorial board, he is critical of the statist measures (expanded government, racial quotas, etc.) which many leftists advocate, arguing that they hurt blacks instead of helping them.

Four decades Riley’s senior, Sowell has a long track record of making similar arguments. Interestingly though, he initially held very different views.

A Marxist radical from a young age, Sowell overcame the burdens of being a school dropout and worked his way to a Harvard economics degree.

Finding that “smug assumptions were too often treated as substitutes for evidence or logic” among the Harvard elite, Sowell’s years of working within the government bureaucracy gradually led him to believe that it was not helping minorities: as shown by his fellow bureaucrats’ disinterest in evidence demonstrating that the higher minimum wage laws they advocated were increasing unemployment among disadvantaged groups.

One of the highlights of “Maverick” is Riley’s description of Sowell’s difficulties as a teaching professor in the 1960s and 1970s, prior to his appointment as a Senior Fellow in the Hoover Institution in 1980s, after which Sowell was able to concentrate on research and writing.

As someone who had been raised in a poor and uneducated family, Sowell understood the importance of education and was particularly eager to help educate other African-Americans.

Despite receiving offers of teaching positions at more prestigious colleges, Sowell decided to return to his original alma mater, the predominantly black Howard University.

His refusal to accept laziness or declining academic standards among his students caused him problems here and in other colleges at a time when American colleges were at the epicentre of a cultural revolution.

“Curricula were being reworked to accommodate ideological fashions. Race and gender and class were becoming preoccupations in student scholarship and faculty tenure decisions. And the notion that education must be “relevant” to the students – especially to minority students from different backgrounds – was ascendant,” Riley writes, and Sowell found it hard to adapt.

In addition to being something of a cultural anomaly for trying to uphold traditional standards, Sowell also refused to go along with politically correct social policies which he saw were not working.

While teaching at the prestigious Cornell University, Sowell observed that the college’s policy of admitting black students who did not meet their usual academic standards in the name of diversity was resulting in gifted students (who may have thrived elsewhere) struggling in their classes.

Though he appears to have initially been reluctant to engage on questions pertaining to race such as this, Sowell’s insistence on examining the facts and his willingness to criticise progressive ideology earned him the animosity of many in the black establishment.

This was often expressed in vicious ways: when it was rumoured that President Reagan would appoint Sowell to his cabinet, a leading NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) official publicly compared him to the “house n*****s” of the plantation era.

A key criticism which Sowell levelled against so-called “leaders” of black America was their overemphasis on achieving political power (often sought for their own benefit) while members of their community suffered due to the breakdown of the traditional family and the poor-quality public services which those same political leaders were responsible for.

In a number of books on related topics – his titles included Ethnic America, Race and Culture, Conquests and Cultures and Affirmative Action Around the World — Sowell shone a light on how educational and income disparities came to exist between different groups, and how politically successful minorities (like Irish-Americans, who dominated America’s big cities as well as the hierarchy of the Catholic Church) sometimes lagged behind others in material terms while politically marginalised groups like the (Chinese diaspora in southeast Asia or the Jews of America) thrived economically and educationally.

Unsurprisingly, this did not endear him to politicians and activists who owed their positions and incomes to maintaining the view that income disparities were always the result of discrimination, which they of course maintained could only be addressed by political action.

Though Sowell’s courage and insights when it comes to issues of race are more necessary now than ever, his career offered so much more, as Riley makes clear here.

As an economist, Sowell earned the admiration of laymen with valuable and accessible books such as Basic Economics, while winning praise from other leading economists for more advanced materials such as Knowledge and Decisions.

Elsewhere, his informal trilogy about the history of ideas — A Conflict of Visions, The Vision of the Anointed and The Quest for Cosmic Justice – has helped to explain the differences in political psychology between Right and Left.

Sowell’s life has imbued in him a toughness which made him well-suited to the role he has played, one which has come at a cost.

“Sometimes it seems as if I have spent the first half of my life refusing to let white people define me and the second half refusing to let black people define me,” Sowell has reflected. Now in his 90s, he will probably never receive the recognition, which he richly deserves, as one of the world’s great intellectuals.

Throughout this excellent biography, Jason Riley provides an outstanding introduction to a truly great man whose work should continue to inspire us.

This content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.

AUTHOR

James Bradshaw

James Bradshaw writes on topics including history, culture, film and literature. More by James Bradshaw

EDITORS NOTE: This MercatorNet column is republished with permission. ©All rights reserved.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!