How Atheist Anti-Capitalists Miss the Point

If an economist sees the handiwork of God in the economy, does that invalidate his economic arguments from a secular perspective?

The great economist Ludwig von Mises, who himself was either atheist or agnostic, noted that:

“Many economists, among them Adam Smith and Bastiat, believed in God. Hence they admired in the facts they had discovered the providential care of ‘the great Director of Nature.’ Atheist critics blame them for this attitude.”

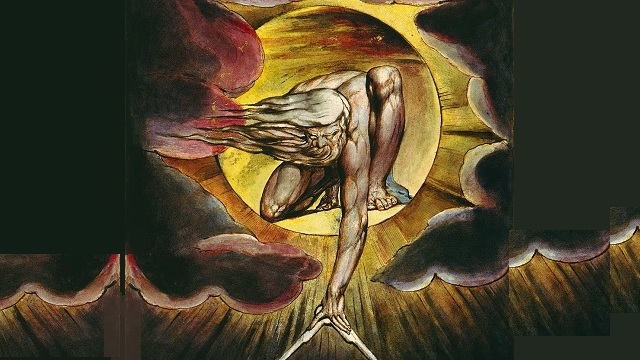

A Transcendent Order

For instance, Adam Smith famously wrote of how producers in a market economy are “led by an invisible hand” to benefit the public even when they only seek private profit.

And Frédéric Bastiat warned humanity against “rejecting the order God has given it” in favor of the grand schemes of social reformers.

Leonard Read, in his essay “I, Pencil” wrote of how, in the market production of a pencil, “we find the Invisible Hand at work.” His pencil narrator concludes, “Since only God can make a tree, I insist that only God could make me.”

All three thinkers contributed mightily to the case for the free market. Anti-capitalist critics have tried to dismiss that case as relying on religious faith, citing the references to God and the invisible hand. Free-market defenders have countered that Smith, Bastiat, and Read were speaking figuratively, not literally.

However, even if they were speaking literally, and even if atheism is true, it still would not invalidate their arguments. That is because those arguments did not rely on a divine characterization of the economy.

The point being made by Smith, Bastiat, and Read in the relevant passages is that, in an economy consisting of acting human individuals, there is a perceivable order that emerges from the planned actions of those individuals but that transcends the plans of any single individual. In that sense, the market order is transcendent relative to the order created by any single market participant.

Smith, Bastiat, and Read demonstrated that transcendent order using economic reasoning and empirical observations about human nature. That demonstration did not rely at all on religious premises. This is plain to see in any honest reading of Smith’s Wealth of Nations, Bastiat’s Economic Harmonies, and Read’s “I, Pencil.” Whether those men saw in that transcendent order something literally divine has no bearing on the validity of their reasoned demonstration of that order.

Newton and God

A cross-discipline comparison may make this point easier to see.

Whereas Smith, Bastiat, and Read examined the economic order of society, Sir Isaac Newton studied the physical order of the material universe. And it is well-established that Newton, as Mises said of Smith and Bastiat, “admired in the facts [he] had discovered the providential care of ‘the great Director of Nature.’”

For instance, Newton wrote in his Optics, “Whence is it that Nature doth nothing in vain? And whence arises all that order and beauty which we see in the world?” “From God” was clearly Newton’s answer.

Would anti-capitalist atheists argue that that discredits Newton’s physics?

Surely not. They would acknowledge in this case what they refuse to acknowledge in the other: that Newton demonstrated the order of the physical universe using reason and evidence, and that whether he saw in that order something literally divine has no bearing on the validity of his reasoned demonstration.

Why the double-standard? It is probably due to the fact that the critics of Smith, Bastiat, and Read have an axe to grind against capitalism, but not physics. And they are particularly loath to concede that there is a transcendent order to the market, because such an order would put a crimp in their plans.

The Borders of Utopia

As Mises wrote, throughout most of history people assumed that “there was in the course of social events no such regularity and invariance of phenomena as had already been found in the operation of human reasoning and in the sequence of natural phenomena.”

In other words, people assumed there were no social equivalents to the laws of logic, math, and physics circumscribing human endeavors. Oblivious to any such restrictions, “Speculative minds drew ambitious plans for a thorough reform and reconstruction of society.” As Mises wrote:

“They did not search for the laws of social cooperation because they thought that man could organize society as he pleased. If social conditions did not fulfill the wishes of the reformers, if their Utopias proved unrealizable, the fault was seen in the moral failure of man. Social problems were considered ethical problems. What was needed in order to construct the ideal society, they thought, was good princes and virtuous citizens. With righteous men any Utopia might be realized.

The discovery of the inescapable interdependence of market phenomena overthrew this opinion.” (…)

“In the course of social events there prevails a regularity of phenomena to which man must adjust his actions if he wishes to succeed.”

In other words, economists discovered economic laws that, together, make up a transcendent, immutable order to the market society. And human beings ignore those laws and that order at their own peril.

As Dave Prychitko put it, “Economics is the art of putting parameters on our utopias.” Economic laws can be denied, but they cannot be defied, even by the grandest kings, the most ingenious lawgivers, the most brutal dictators, the most ambitious central planners, or the most self-righteous social reformers.

A president who thinks he can defy the law of supply and demand and impose price ceilings without incurring shortages will fail, just as he would if he thought he could defy the law of gravity by stepping off his presidential palace without falling.

And any bureaucrat who, in defiance of “the knowledge problem,” thinks he can outperform the free-market price system in coordinating the production of pencils will similarly fail, as Leonard Read’s “I, Pencil” makes plain.

Those who try to dismiss “I, Pencil” do not want to admit that they or their favorite social schemers cannot outsmart or outdo the transcendent order of the market. Those who sneer at the invisible hand want a free hand to remold society as they please.

But intellectually honest secular thinkers unburdened by such an agenda will not get hung up on any differences over religion they have with Smith, Bastiat, and Read. Like Mises, they will see the wisdom in acknowledging, respecting, and even wondering at the transcendent order of the market society, whether or not they attribute that order to God.

AUTHOR

Dan Sanchez

Dan Sanchez is the Director of Content at the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE) and the editor-in-chief of FEE.org. Follow him on Substack and Twitter.

EDITORS NOTE: This MercatorNet column is republished with permission. ©All rights reserved.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!