The Great Historian Who Understood that Religion is the Key to Understanding History

A guide to making sense of two thousand years of Western civilization.

The impact of Christopher Dawson’s thought has long reflected the boldness of his books and the modesty of his character. His books radiate the intellectual power of his historical vision, while his quiet personality has been apt to work at the personal rather than the corporate level, inspiring individual minds rather than institutional movements.

Dawson died in 1970 after half a century of significant publication. His reputation fell into the usual trough of posthumous neglect, but by the 1990s it had recovered, leading to various studies of his thought, new editions of his books (including a Collected Works series published by the Catholic University of America Press), and several educational initiatives to implement his ideas on the study of Christian culture as the vitalising source of Western civilisation.

Joseph Stuart has played an active role in this revival, both as a history professor at the University of Mary in North Dakota and through his academic writing, including a new Introduction he wrote in 2015 to Dawson’s book on the French Revolution, The Gods of Revolution.

He has now produced a full-length — and much-anticipated — study of Dawson, which is a biography in two senses. On the one hand, it sheds light on Dawson’s life, which was that of a reclusive scholar who became publicly prominent on rare occasions; and thus it provides a valuable supplement to the definitive biography of Dawson, A Historian and His World (1984), by his daughter, Christina Scott.

On the other hand, it is an intellectual biography. It unfolds Dawson’s ideas in exhaustive detail, revealing that he was an intellectual trailblazer whose vital insights into the role of religion in historical development and cultural change have yet to be widely appreciated.

Stuart’s approach is admirably expressed in the subtitle of his book. He explores Dawson’s life and intellect in terms of his “cultural mind”, tracing in the opening chapters its formation in the aftermath of the First World War (1914-18), and in the later chapters its application to the two crucial areas of politics and education.

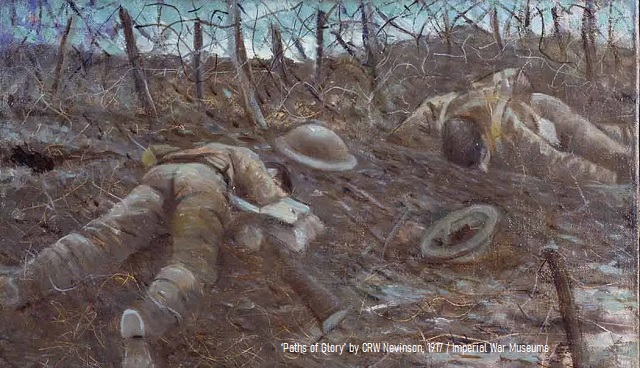

While “The Age of the Great War” may at first seem limiting, as though the author is confining his study to a remote event a century ago, he presents a convincing case of the Great War’s profound and permanent impact on subsequent history. This tumultuous event in the first half of the century set in train a vast unravelling of the culture of the West — spiritually, morally, and politically – and paved the way for the dramatic changes more usually associated with the second half, particularly from the 1960s onwards.

Dawson was an unconventional historian. He focused on the life and experience of cultures rather than nations or states, on large themes instead of narrow topics, over long historical periods, not short time frames.

His most influential books bear titles such as The Making of Europe: An Introduction to the History of European Unity (1932), which showed how the slow and silent dissemination of Christianity in the Dark Ages brought about the bountiful culture of medieval Christendom; The Movement of World Revolution (1959), which explored the religious and cultural effects of Western and Christian global expansion; and The Dividing of Christendom (1965), which revealed the contributions of the Reformation and the Enlightenment to the divorce of faith from life and thought that culminated in the secularisation of the modern West.

Dawson’s cultural mind was formed at a time when the social sciences were emerging as new fields of study. The perspectives of sociology and anthropology, as Stuart explores thoroughly in separate chapters, illuminated Dawson’s approach to history. They helped him to develop a highly integrated mind, best described by John Henry Newman (whose thought influenced Dawson deeply) as “the power of viewing many things at once as one whole”.

These new disciplines made clear to Dawson the formative role of religion in human history. As he wrote in 1948:

“Religion is the key to history. We cannot understand the inner form of a society unless we understand its religion. We cannot understand its cultural achievements unless we understand the religious beliefs that lie behind them. In all ages the first creative works of a culture are due to a religious inspiration and dedicated to a religious end.”

Dawson’s distinctive approach was to penetrate the inner life of a culture. He saw a culture from within, recognising that its traditions and customs, its feasts and rituals, its art and architecture, its literature and music, are inspired by the deepest human impulses. He did not discount the importance of external factors, such as economic structures or social conditions, but he knew that it was spiritual needs which inspire and guide human beings who inhabit those structures and conditions – that, finally, a culture is not only a material way of life but a spiritual and moral order.

Dawson recognised that, when the religious impulse is disregarded or else privatised and deprived of any public role, as in the contemporary West, the effects will be profound and disturbing. The yearning for transcendental meaning and purpose does not simply fade away. It finds new and menacing expression in substitute faiths, usually in philosophical and political forms.

Stuart devotes two excellent chapters to the rise of “political religions” as the characteristic form of substitute faith in our time. With painstaking scholarship he shows how Dawson’s insights into the cultural importance and power of religion enabled him to interpret the appeal of secular ideologies, such as Nazism and Communism, which function culturally like religions. They convert earthly causes into transcendental faiths, which finally fail because they do not correspond to genuine transcendental realities.

Dawson’s insights into political religions, as Stuart shows from his wide research, have been endorsed by present-day scholars as the spiritual appeal of totalitarian control has become unmistakable. Dawson was prophetic in seeing that a totalitarian solution would appeal to democracies, not just to authoritarian societies – an extension of power recently seen in the Covid response of Western countries, where the promise of social protection was used politically to crush long-cherished freedoms.

The final chapter of Stuart’s book is devoted to the seminal influence of Dawson’s cultural mind on education. In Dawson’s view, the survival of a culture depended on the continuity of its educational tradition, which supplied a common world of thought and moral values and a shared inheritance of knowledge and memory. Any rupture of this educational tradition was far more destructive than any political or economic change, for it finally meant the death of the culture itself.

Dawson believed the secularised West could not survive without a recovery of Christian faith, and that the pathway to this recovery would be educational, especially in the American system of Catholic higher education. He proposed the study of Christian culture as a social reality across the centuries, which could reanimate a Christian sense of identity in a culture no longer friendly to religion and make possible the passing on of a heritage of faith to new generations.

As Stuart documents in depth, Dawson’s educational ideas did not strike root during his lifetime, for reasons of the dual focus on the Graeco-Roman classics in the humanities and on philosophy and theology in Catholic institutions, both of which were threatened by a cultural approach to the centuries of Christian history. Yet in the half-century since Dawson’s death, various programs inspired by his ideas have been implemented – at several Catholic universities in America and at Campion College in Australia.

The 19th century French scholar Ernest Renan foresaw the ramifying effects of the abandonment of Christianity in the West. It began with the collapse of supernatural belief and would inevitably lead to a collapse of moral convictions. “We are living,” he wrote, “on the perfume of an empty vase.”

The cultural perspectives of Christopher Dawson help to explain why even the perfume is now evaporating. They make the reading of Joseph Stuart’s impressive study not only timely but insistently urgent.

AUTHOR

Karl Schmude

Karl Schmude is co-founder of Campion College in Sydney and a former university librarian. He is the author of short biographies of Christopher Dawson (2022) and G.K. Chesterton (2008) and has published… More by Karl Schmude

EDITORS NOTE: This MercatorNet column is republished with permission. ©All rights reserved.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!