There would be no risk if the future were known and all of one’s plans played out exactly as expected. Because of pervasive uncertainty, a variety of risks permeates all human endeavors.

It is a common human desire to want to feel secure, to want to avoid as much risk as possible and live a comfortable, protected life. But different people deal with risk in different ways. Not all people are risk-avoiders.

For example, artists take risks with each work. In his Lectures on Shakespeare, W.H. Auden draws a distinction between a minor writer and a major one. This distinction hinges on the writer’s appetite for risk-taking and his ability to break new ground. A minor writer (Auden used the example of the poet A.E. Housman) is one who finds his niche and sticks to it. “The minor writer never risks failure,” Auden states. On the other hand, the major writer, like Shakespeare, pushes himself to discover new problems and try new things. In a word, the major writer takes risks. According to Auden, “Shakespeare is always prepared to risk failure. Troilus and Cressida, Measure for Measure, and All’s Well that Ends Well don’t quite come off, whereas almost every poem of Housman does.” Yet Shakespeare risked enough so that his successes have earned him almost universal acclaim as a great writer.

The same can be said of musicians. Great jazz artists like Charlie Parker and Miles Davis pushed their art in new and different directions, taking risks when they had no assurance they would succeed. Their experimental play earned them places in the pantheon of jazz immortals.

Gamblers are other examples of people who willingly take risks. In fact, gamblers who frequent the gaming tables create risks in playing various games. Sometimes they are lucky. The tale of Charles Wells is a case in point. In 1891 Wells gained fame by “breaking the bank” at Monte Carlo three times in one year. One evening he played the wheel and left his chips on the number 5, with the odds 36 to 1. The number five came up five times in a row. He walked out with the equivalent of over one million dollars. He was written up in the newspapers and even had a song about him (“The man who broke the bank at Monte Carlo”). Ironically, Wells would die broke.

In any event, whatever happens to the artist or to the gambler happens to him alone (and perhaps his backers, should he have any). In other words, if Shakespeare wrote a clinker, Ben Jonson didn’t have to come out of pocket to support him. In a similar way, the gambler who loses his shirt has no claim against sober individuals who choose not to gamble. Conversely, Shakespeare’s fame is his alone and the gambler’s winnings are his too.

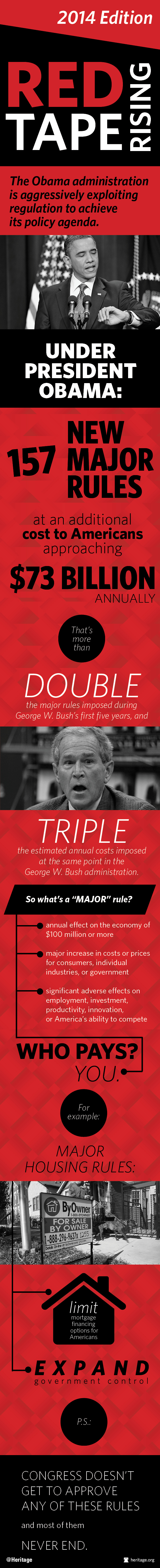

However sensible this arrangement seems, it often does not prevail in the modern world where collectivist thinking is rampant. In real life successful people indirectly support those who are unsuccessful. In some cases successful people do this voluntarily by contributing their time and money to charity. But more often, successful people support others whether they want to or not, since their pockets are regularly picked by government officials of every stripe. The government encourages the illusion of a mighty shield that will protect people from their own imprudence and misfortune rather than let them take care of themselves, which would require them to save, to plan, and to be prudent.

The existence of a forced safety net, or a support system not voluntarily funded, warps the normal incentives and changes people’s behavior, in perverse ways.

Banking and Risk

Look at the banking world. If a bank makes a series of poor decisions that lead to failure, the FDIC stands ready to make good on any losses depositors should suffer. Here we have two problems. The first is that the banker is not held accountable for his losses. And the second is that the depositor is relieved of the responsibility for where he puts his money. All he has to know is whether his bank is FDIC-insured.

This would be like giving your money to Charles Wells knowing that the house will reimburse him for any losses he suffers and that he will in turn reimburse you. Do you think that this would change Wells’s behavior? Do you think that he might take some risks that he otherwise might not take? And what if Shakespeare knew that no matter how bad any particular play was, he would get reimbursed for any losses incurred? It is common sense to acknowledge that risk influences behavior.

In more formal terms, a moral hazard is created when the adverse consequences of risk-taking are transferred to a third party and the transfer benefits the risk-taker and harms the third party. Insurance is often cited as a common example of risk transfer. However, most insurance is created in the marketplace and is priced, like all goods and services in the market, by the interplay of buyers and sellers. In other words, insurance is not persistently mispriced. The fact that the FDIC determines the price of insurance necessarily means that it will likely be higher or lower than the market price. Risk will always be too cheap or too dear. Occasionally, perhaps, the FDIC hits the market price. Then the question becomes, why not let the market run this insurance program?

Then again, deposit insurance is really not insurance at all. Just because the government calls it insurance doesn’t mean it is. No other industries have insurance like it. When Amazon or General Motors or Dell takes a loss, no one reimburses the company for it. Entrepreneurial risk is inherently uninsurable. Insurance protects against certain kinds of risks, but it doesn’t underwrite failure.

Behavioral Boundaries

If the theory of moral hazard is correct, then risk—the possibility of loss, the element of chance—serves a useful purpose in changing behavior. Risk can keep people within certain behavioral boundaries.

Few would dare cross a busy street without at least looking to see if any cars were coming. The risk of being hit and its attendant consequences are simply too great. People modify their behavior to deal with these risks. They mitigate them, in this case, by looking both ways before crossing the street. Further, a pedestrian may choose to cross only when the light is in his favor. These are some of the ways people deal with risks of crossing a busy street. The risk of being hit forces them to think before they act.

In banking, the theory of moral hazard is no different. Benjamin Esty of the Harvard Business School conducted a valuable study on the impact of contingent liability on commercial bank risk-taking.* Esty looked at the banking world prior to deposit insurance. From the passage of the National Banking Act of 1863 until 1933 regulators imposed double liability—a form of contingent liability—on national bank shareholders. Esty explains: “Under this system, shareholders were doubly liable in that they could lose both the market value of their shares and, through assessment, an amount equal to the par value of equity to cover creditor obligations including deposits and other debts.” Most banks at the time had a par value of $100 per share. So, as a shareholder, if your bank went belly up you would lose the market value of your stock and you could be assessed another $100 per share to cover depositor and other losses. Do you think that this would change your behavior as an owner of a bank?

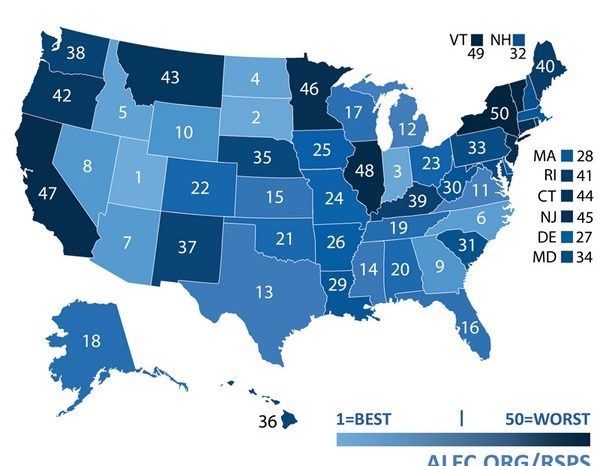

The states passed their own versions of contingent liability as well. Some had single liability. California had triple liability. And regulators were effective at collecting assessments. During the years 1865 through 1934, the comptroller of the currency collected 51 percent of the assessments. The fact that these assessments were creditable is shown in the behavior of the banks and their risk-taking activities. As Esty notes, from 1865 to 1933 voluntary bank liquidations accounted for over 70 percent of all bank closures. The states had similar experiences with state-chartered banks.

In an FDIC world there is no incentive for banks to close or liquidate as soon as trouble arises. And since bank shareholders have limited liability, their appetite for risk is greatly enhanced. Banks of the nineteenth century were fortress-like compared to their late twentieth-century counterparts. They had reserves of gold and silver, and by law their reserves had to cover 25 percent of deposits. Some banks, like National City, carried reserves to cover 60 percent of deposits.

This is not to recommend that contingent liability is the way to enforce bank soundness, but rather to illustrate how the risk of loss changes behavior and forces prudence in a way that FDIC insurance lacks.

Other Interventions

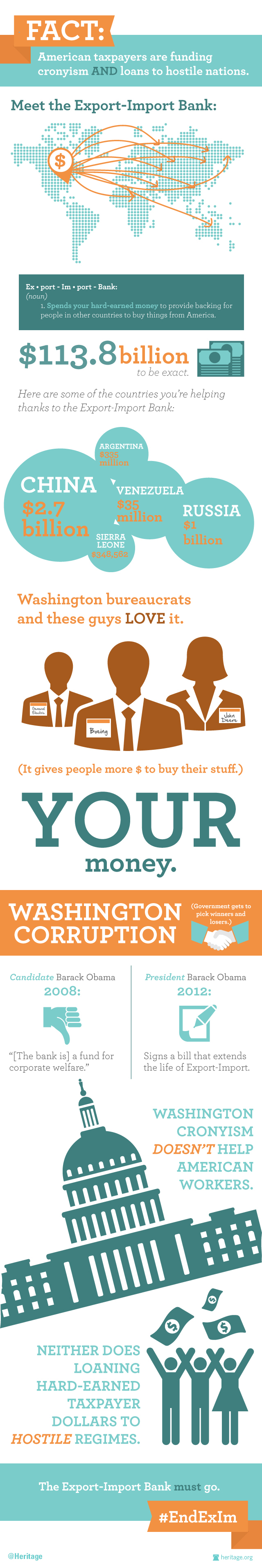

Deposit insurance is only one commonly known way that governments try to collectivize and minimize risk. They have numerous other programs and guarantees that seemingly lower risk. Another example is the Small Business Administration (SBA), which provides banks with a partial guarantee of loans made to certain favored classes. If a minority-owned business, financed under an SBA loan, fails, the SBA stands in to absorb a portion of that debt. This encourages the banks to take risks that they otherwise would not take.

Removing or shifting risk by government fiat is not a panacea. Genuine risk serves a useful purpose. Forcing the shifting of risk to third parties, in essence creating moral hazard, leads to the perverse outcome that the risk one hoped to avoid is actually recreated in the form of the false promises made by the welfare state.

*“The Impact of Contingent Liability on Commercial Bank Risk Taking,” Journal of Financial Economics, February 1998, pp. 189–218.

Christopher Mayer is a commercial loan officer and freelance writer.

EDITORS NOTE: The featured image is courtesy of FEE and Shutterstock.