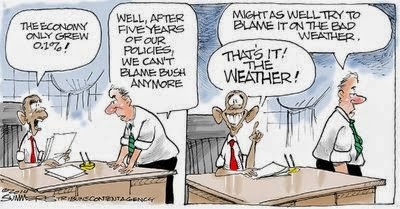

Two headlines on Tuesday, March 18, are bound to give Democrats across the country a really bad case of heartburn. The Washington Free Beacon headline read: “Born to Run Away From High Taxes,” while a New York Times headline read, “Businessman Wins Republican Primary for Governor in Illinois.”

The Free Beacon story details the extent to which “New Jersey’s high taxes may be costing the state billions of dollars a year in lost revenue as high earning residents flee (the state).” According to the Free Beacon story, the study,” titled Exodus on the Parkway, was completed last year by Regent Atlantic, of Morristown, New Jersey, but held for publication until after the 2013 elections. The study stated it intentionally withheld its results because 2014 is not an election year for state legislators… and the dire findings of the study would “hopefully encourage a serious and objective dialogue aimed at addressing and solving the challenges that New Jersey currently faces.”

The study found that, since the Democrat-controlled legislature passed the “millionaire’s tax” in 2004, signed into law by Democratic Governor Jim McGreevey, New Jersey has been steadily losing high-net-worth residents. That ill-advised and counter-productive approach to revenue enhancement, which presupposes that the rich will just sit still forever and allow themselves to be taxed back into the middle class, or worse, imposed a 41 percent increase in the state income tax on those with annual incomes of $500,000, or more.

Lacking the capacity to understand basic economic principles, and having no ability to learn from their mistakes, New Jersey Democrats have continued to push for even higher taxes on the wealthy. Under threat of veto by a tough-minded Republican governor, Chris Christie, they have failed on three successive attempts.

According to the Regent Atlantic study, New Jersey collects $10 billion annually in personal income taxes, $4.2 billion of which is paid in by just one percent of the population. Before the millionaire’s tax was enacted, the aggregate net worth of New Jersey residents increased by $98 billion over a four year period. However, in the four year period following the tax increase, 70 percent of that aggregate increase in net worth has fled the state. Because New Jersey residents have learned how to vote with their feet, the state lost taxable income of $5.5 billion in 2010 alone because residents moved to more tax-friendly states.

However, it’s not just the wealthy that New Jersey Democrats wish to bilk in their never-ending quest to buy enough votes to maintain themselves in power. Democrats in the legislature have also proposed a five-cent-per-gallon increase in the gasoline tax, a tax on water consumption, a tax on plastic bags, a tax on plastic water bottles, and yet another increase in the income tax. These are increases that would damage everyone who lives in or drives through the Garden State.

Apparently New Jersey Democrats believe that they have reached nirvana when a majority of the people are on food stamps, AFDC, Medicaid, unemployment compensation, and workman’s compensation, while the state confiscates 100 percent of the incomes and assets of those foolish enough to continue working… those for whom a job offer in Detroit would look like the opportunity of a lifetime.

Some 800 miles to the west, in Illinois, the state that currently resembles Detroit more than any other, wealthy private equity manager, Bruce Rauner, has won the Republican nomination for governor. Rauner, who spent $6 million of his own money in a four-way race for the GOP nomination, won 40.1% of the vote in defeating three better known GOP candidates, all long-time GOP officials in Springfield.

If Rauner is elected… and it looks as if he has the right stuff to get the job done… he will be taking on the toughest job of any Republican governor in the nation. Illinois is, after all, an economic basket-case, the worst run, most corrupt state in the nation.

On January 12, 2011, Investors Business Journal reported that the State of Illinois faced a budget deficit of $15 billion, “equivalent to more than half the state’s general fund.” According to the report, “(Illinois) officials warned that state government might not be able to pay its employees. It certainly would fall further behind in paying the businesses, charities, and schools that provide services on the state’s behalf.”

In response to that economic tsunami, the Governor of Illinois, Democrat Pat Quinn, and the Illinois legislature, controlled by Democrats (35-24 in the Senate and 64-54 in the House), developed a response that only a bunch of Democrats would see as a viable solution. In the midst of a major national recession they increased personal income taxes by 66% and corporate taxes by 46%, increases that were expected to produce an additional $6.8 billion per year… assuming, of course, that every employer then in Illinois, would remain in Illinois.

A year later, the Illinois Comptroller’s Office estimated that the backlog of unpaid bills was nearly $8 billion… and this after Democrats in Springfield placed a crushing load of new taxes on the shoulders of taxpayers and corporations.

Reactions were predictable. According to the Journal, neighboring states immediately began plotting to “lure business away from Illinois.” Governor Scott Walker (R-WI) said, “Years ago, Wisconsin had a tourism advertising campaign targeted to Illinois with the motto, ‘Escape to Wisconsin.’ Today we renew that call to Illinois businesses, ‘Escape to Wisconsin.’ You are welcome here.”

Then-Governor Mitch Daniels (R-IN) said, “It’s like living next door to the ‘Simpsons’ – you know, the dysfunctional family down the block.” Gov. Daniels may have mixed a metaphor. To say that living next door to Illinois is like living next door to the Adams Family may have been a more apt comparison.

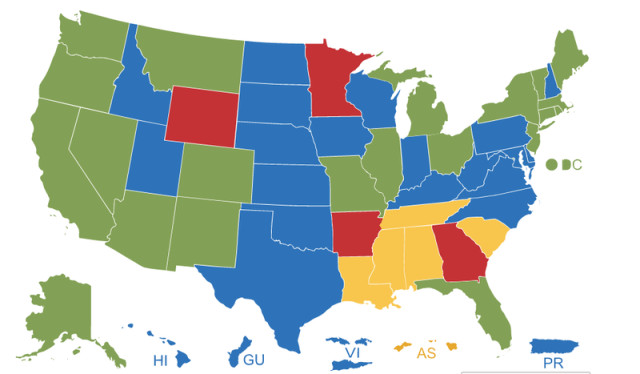

But now it appears that Republicans are about to field a candidate with some business sense who is not afraid to tell the people of Illinois what they need to hear, while Democrats continue to insist on telling them whatever is necessary to get their votes on Election Day. And while union leaders in Illinois could not have failed to notice that their state is now surrounded by states where right-to-work was once thought to be impossible… Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin… right-to-work is probably not something that will happen in Illinois until a hard-nosed Republican governor can make Republicanism respectable everywhere in the state except in America’s most corrupt city… Chicago.

Bruce Rauner may be that man. According to the Times story, Rauner has already angered the public sector unions. He has criticized union leaders, advocated charter schools, and suggested that recent reforms in the public employee pension system… with unfunded liabilities of about $80 billion… were far too timid.

Never in American history has a political party been as vulnerable to resounding defeat as is the Democrat Party in 2014. The only thing the Republican Party needs is leadership. With John Boehner (R-OH) as Speaker of the House, with Mitch McConnell (R-KY) as Minority Leader of the Senate, and with Eric Cantor (R-VA) as House Majority Leader, the GOP is in great danger of wasting the opportunity to literally devastate the Democratic Party. Never before have there been three political leaders more capable of snatching defeat from the jaws of victory.

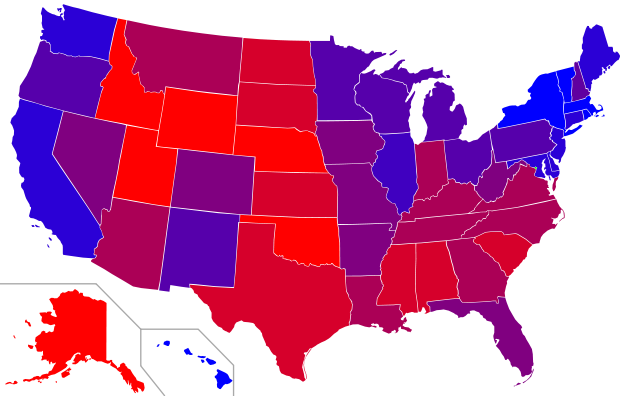

Although most pundits agree that Republicans will maintain their majority in the House of Representatives, many hedge their bets by saying that the party could actually lose a few seats in the House. I believe the Republicans will maintain their majority in the House, picking up an additional five to ten seats in the process.

In the Senate, most pundits hedge their bets by predicting that Republicans have a shot at taking control, but with a slim majority of only one or two seats. I believe that those predictions are far too conservative and fail to take into account the foul mood of the American people and the intense unpopularity of Barack Obama, Harry Reid, and Nancy Pelosi.

Republicans have 15 Senate seats at stake. I believe Republicans will retain all of those seats. On the other hand, the Democrats have 21 seats at stake, only eight of which are all but certain to remain in Democrat hands. The remaining 13 seats are either leaning heavily Republican or are vulnerable to Republican takeover. A net gain of 10 seats by the GOP is not outside the realm of possibility.

All we need are leaders and candidates who are willing to take the battle to the enemy in a most forceful and straightforward way. At a recent rally in Illinois, Bruce Rauner shouted, “Let’s shake up Springfield! Let’s go get ‘em!” Republicans should never doubt that we have the people and the issues on our side. And if we can get Republicans across the country to adopt that same rallying cry, to say, “Let’s shake up America! Let’s go get ‘em!” we can win a victory in November that will make the Republican Revolution of 1994 pale by comparison.

EDITORS NOTE: The featured map is courtesy of Theshibboleth. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.