Market Corrections Inspire Dangerous Political Panic by Jeffrey A. Tucker

Some kinds of inflation people really hate, like when it affects food and gas. But now, with the whole of the American middle class heavily invested in stocks, there is another kind inflation people love and demand: share prices that increased forever.

Just as with real estate before 2008, people seem addicted to the idea that they should never go anywhere but up.

This is the reason that stock market corrections are so dangerous. The biggest danger is not economic. It is political. Such corrections push politicians and central bankers to undertake ever-more nutty political in do order to fix them.

To make the point, Donald Trump immediately blamed China, which has the temerity to sell Americans excellent products at low prices. Bernie Sanders blamed “free trade,” even though the United States is among the most protectionist in the world.

Nothing in this world is more guaranteed to worsen a correction that a trade war. But so far, that’s what’s been proposed.

Tolerance for Downturns

It was not always so. In the 1982 recession, the Reagan administration argued that it was best to let the market clear and grow calm. Once the recession cleaned up misallocations of resources, the economy would be well prepared for a growth path. Incredibly, the idea was sold to the American people, and it proved wise.

That was the last time in American history we’ve seen anything like a laissez-faire attitude prevail. After the 1990s dot com boom and bust, the Fed intervened in an effort to repeal gravity. After 9/11, the Fed intervened again, using floods of paper money to rebuild national pride. That created a gigantic housing bubble that exploded 7 years later.

By 2008, the idea of allowing markets to clear became intolerable, and so Congress spent hundreds of billions of dollars and the Fed created trillions in phony money, all to forestall what desperately needed to happen.

Now, with dramatic declines in stock markets around the world, we are seeing what happens when governments and central banks attempt to counter market forces.

Markets win. Every time. But somehow it doesn’t matter anymore. There’s no more science, no more rationality, no more concern for the long term, so far as the Fed is concerned. The Fed is maniacally focused on its member banks’ balance sheets. They must live and thrive no matter what. And the Fed is in the perfect position now to use public sentiment to bolster its policies.

The Right and Wrong Question

In the event of a large crash, the public discussion going forward will be: What can be done to re-boost stock prices? This is the wrong question. The right question should be: What were the conditions that led to the unsustainable boom in the first place? This is the intelligent way to address a global meltdown. Sadly, intelligence is in short supply when people are panicked about losing their retirement funds they believed were secure.

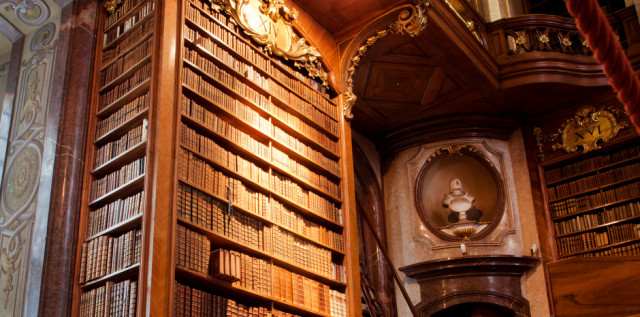

Back when people thought about such things, the great economic Gottfried von Haberler was tapped by the League of Nations to write a book that covered the whole field of business cycle theory as it then existed. Prosperity and Depressioncame out in 1936 and was republished in 1941. It is a beautiful book, rooted in rationality and the desire to know.

The book covers six core theories: purely monetary (now called Chicago), overinvestment (now called Austrian), sudden changes in cost (related to what is now called Real Business Cycle), underconsumption (now called Keynesian), psychological (popular in the financial press), and agricultural theories (very old fashioned).

Each one is described. The author then turns to solutions and their viability, assessing each. The treatise leans toward the view that permitting the recession (or downturn or depression) run its course is a better alternative than any large policy prescription applied with the goal of countering the cycle.

Haberler is careful to say that there is not likely one explanation that applies to all cycles in all times and in all places. There are too many factors at work in the real world to provide such an explanation, and no author has ever attempted to provide one. All we can really do is look for the primary causes and the factors that are mostly likely to induce recurring depressions and recoveries.

He likened the business cycle a rocking chair. It can be still. It can rock slowly. Or an outside force can come along to cause it to rock more violently and at greater speed. Detangling the structural factors from the external factors is a major challenge for any economist. But it must be done lest policy authorities make matters worse rather than better.

The monetary theory posits that the quantity of money is the key factoring in generating booms and busts. The more money that flows into an economy via the credit system, the more production increases alongside consumption. This policy leads to inflation. The pullback of the credit machine induces the recession.

The “overinvestment” theory of the cycle focuses on the misallocation of resources that upsets the careful balance between production and consumer. Within the production structure in normal times, there is a focus on viability in light of consumer decisions. But when more credit is made available, the flow of resources is toward the capital sector, which is characterized by a multiplicity of purposes. The entire production sector mixes various time commitments and purposes. Each of them corresponds with an expectation of consumer behavior.

Haberler calls this an overinvestment theory because the main result is an inflation of capital over consumption. The misallocation is both horizontal and vertical. When the consumer resources are insufficient to realize the plans of the capitalists, the result is a series of bankruptcies and an ensuing recession.

Price Control by Central Banks

A feature of this theory is to distinguish between the real rate of interest and the money rate of interest. When monetary authorities push down rates, they are engaged in a form of price control, inducing a boom in one sector of the production structure. This theory today is most often identified with the Austrian school, but in Haberler’s times, it was probably the dominant theory among serious specialists throughout the world.

In describing the underconsumption theory of the cycle, Haberler can hardly hide his disdain. In this view, all cycles result from too much hoarding and insufficient debt. If consumer were spend to their maximum extent, without regard to issues of viability, producers would feel inspired to produce, and the entire economy could run off a feeling of good will.

Habeler finds this view ridiculous, based in part on the implied policy prescription: endlessly inflate the money supply, keep running up debts, and lower interest rates to zero. The irony is that this is the precisely the prescription of John Maynard Keynes, and his whole theory was rooted in a 200-year old fallacy that economic growth is based on consumption and not production. Little did Haberler know, writing in the early 1930s, that this theory would become the dominant one in the world, and the one most promoted by governments and for obvious reasons.

The psychological theory of the cycle observes the people are overly optimistic in a boom and overly pessimistic in the bust. More than that, the people who push this view regard these states of mind as causative of economic trends. They both begin and end the boom.

Haberler does not deny that such states of mind are important and contributing elements to making the the cycle more exaggerated, but it is foolish to believe that thinking alone can bring about systematic changes in the macroeconomic structure. This school of thought seizes on a grain of truth, and pushes that grain too far to the exclusion of real factory. Interestingly, Haberler identifies Keynes by name in his critique of this view.

Haberler’s treatise is the soul of fairness but the reader is left with no question about where his investigation led him. There are many and varied causes of business cycles, and the best explanations trace the problem to credit interventions and monetary expansions that upset the delicate balance of production and consumption in the international market economy.

Large-scale attempts by government to correct for these cycles can result in making matters worse, because it has no control over the secondary factors that brought about the crisis in the first place. The best possible policy is to eliminate barriers to market clearing — that is to say, let the market work.

The Fed is the Elephant in the Room

And so it should be in our time. For seven years, the Fed, which controls the world reserve currency, has held down interest rates to zero in an effort to forestall a real recession and recreate the boom. The results have been unimpressive. In the midst of the greatest technological revolution in history, economic growth has been pathetic.

There is a reason for this, and it is not only about foolish monetary policy. It is about regulation that inhibits business creation and economic adaptability. It’s about taxation that pillages the rewards of success and pours the bounty into public waste. It is about a huge debt overhang that results from the declaration that all governments are too big to fail.

Whether a correction is needed now or later or never is not for policymakers to decide. The existence of the business cycle is the market’s way of humbling those who claim to have the power and intelligence to outwit its awesome and immutable forces.

Jeffrey Tucker is Director of Digital Development at FEE, CLO of the startup Liberty.me, and editor at Laissez Faire Books. Author of five books, he speaks at FEE summer seminars and other events. His latest book is Bit by Bit: How P2P Is Freeing the World. Follow on Twitter and Like on Facebook.