Real Hero Peter Fechter: The Berlin Wall and Those Who Refused to Be Caged by Lawrence W. Reed

For the 28 years from 1961 to 1989, the ghastly palisade known as the Berlin Wall divided the German city of Berlin. It sealed off the only escape hatch for people in the communist East who wanted freedom in the West.

No warning was given before August 13 when East German soldiers and police first stretched barbed wire and then began erecting the infamous wall, not to mention guard towers, dog runs, and explosive devices behind it.

By one estimate, 254 people died there during those 28 years — shot by police, ensnared by the barbed wire, mauled by dogs, or blown to bits by land mines — most of them in the infamous “death strip” that immediately paralleled the main barrier. The communist regime cynically referred to it as the “Anti-Fascist Protection Wall.”

In my home hangs a large, framed copy of a famous photo of a poignant moment from that sad day in 1961. It shows a young, apprehensive East German soldier glancing about as he prepares to let a small boy pass through the emerging barrier. No doubt the boy spent the night with friends and found himself the next morning on the opposite side of the wall from his family. But the communist government ordered its men to let no one pass. The inscription below the photo explains that, at this very moment, the soldier was seen by a superior officer who immediately detached him from his unit. “No one,” reads the inscription, “knows what became of him.” Only the most despicable tyrants could punish a man for letting a child get to his loved ones, but in the Evil Empire, that and much worse happened all the time.

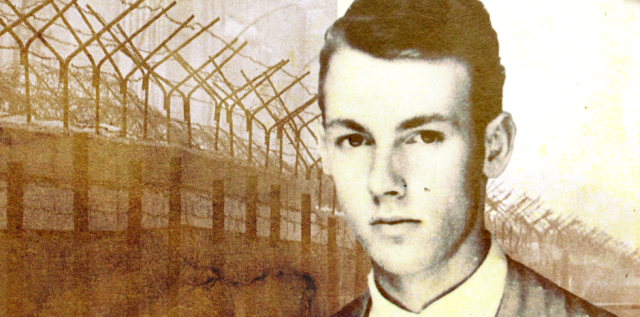

Like millions of others, a strapping 18-year-old bricklayer named Peter Fechter yearned for so much more than the stifling dreariness of socialism. He hatched a plan with a friend, Helmut Kulbeik, to conceal themselves in a carpenter’s woodshop near the wall and watch for an opportune moment to jump from a second-story window into the death strip. They would then run to and climb over the 6½ foot high concrete barrier, laced with barbed wire, and emerge in freedom on the other side.

It was August 17, 1962, barely a year since the Berlin Wall went up, but Fechter and Kulbeik were ready to risk everything. When the moment came that guards were looking the other way, they jumped. Seconds later, during their mad dash to the wall, guards began firing. Amazingly, Kulbeik made it to freedom. Fechter was not so lucky. In the plain view of witnesses numbering in the hundreds, he was hit in the pelvis. He fell, screaming in pain, to the ground.

No one on the East side, soldiers included, came to his aid. Westerners threw bandages over the wall but Fechter couldn’t reach them. Bleeding profusely, he died alone, an hour later. Demonstrators in West Berlin shouted, “Murderers!” at the East Berlin border guards, who eventually retrieved his lifeless body.

Christine Brecht, writing on the Berlin Wall Memorial website, reveals subsequent events involving the Fechter family:

In addition to the painful loss of their only son, the family of the deceased was subjected to reprisals from the East German government for decades. In July 1990 Peter Fechter’s sister pressed charges that opened preliminary proceedings and that ultimately ended in the conviction of two guards. Found guilty of manslaughter, they were sentenced to 20 and 21 months in prison, a sentence that was commuted to probation. During the main proceedings, Ruth Fechter, the victim’s younger sister who served as a joint plaintiff in the trial, expressed herself through her attorneys. They explained that she thought it important to speak out, to no longer be “damned by passivity and inactivity” and to get out of “the objectified role that she had been put in until then.” She movingly described how she and her family experienced the tragic death of her brother and had felt powerless to act against his public defamation. They had been sworn to secrecy, an involuntary obligation that put the family under tremendous pressure. “We were ostracized and experienced hostile encounters daily. They were not born of our personal desire, but were instead imposed on us by others, becoming a central element in the life of the Fechter Family.” After all those years, participating in the trial as a joint plaintiff offered Ruth Fechter an opportunity to participate in the effort to explain, research and evaluate the circumstances of her brother’s death. And she added that the legal perspective occasionally overlooks the fact that in this case “world history fatally intersected with the fate of a single individual.”

The world must never forget this awful chapter in history. Nor should we ever forget that it was done in the name of a vicious system that declared its “solidarity with the working class” and professed its devotion to “the people.”

We who embrace liberty don’t believe in shooting people because they don’t conform, and that is ultimately what socialism and communism are all about. We don’t plan other people’s lives because we’re too busy at the full-time job of reforming and improving our own. We believe in persuasion, not coercion. We solve problems at penpoint, not gunpoint. We’re never so smugly self-righteous in our beliefs that we’re ready at the drop of a hat to dragoon the rest of society into our schemes.

All this is why so many of us get a rush every time we think of Ronald Reagan standing in front of the Brandenburg Gate in 1987 and demanding, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” This is why we were brought to tears in the heady days of 1989 when thousands of Berliners scaled the Wall with their hammers, picks, and fists and pummeled that terrible edifice and the Marxist vision that fostered it.

Peter Fechter and the 253 others who died at the Berlin Wall are real heroes. They deserve to be remembered.

For further information, see:

- Video: “Top Ten Berlin Wall Escapes”

- Video: scenes of the Fechter shooting

- Video (in Spanish): singer Nino Bravo’s 1972 song, “Libre,” in memory of Peter Fechter

- Frederick Taylor’s The Berlin Wall: A World Divided, 1961–1989

- Doug Bandow, “No More Bricks in the Wall”

Lawrence W. (“Larry”) Reed became president of FEE in 2008 after serving as chairman of its board of trustees in the 1990s and both writing and speaking for FEE since the late 1970s.

EDITORS NOTE: Each week, Mr. Reed will relate the stories of people whose choices and actions make them heroes. See the table of contents for previous installments.