For a society that has fed, clothed, housed, cared for, informed, entertained, and otherwise enriched more people at higher levels than any in the history of the planet, there sure is a lot of groundless guilt in America.

Manifestations of that guilt abound. The example that peeves me the most is the one we often hear from well-meaning philanthropists who adorn their charitable giving with this little chestnut: “I want to give something back.” It always sounds as though they’re apologizing for having been successful.

Translated, that statement means something like this: “I’ve accumulated some wealth over the years. Never mind how I did it, I just feel guilty for having done it. There’s something wrong with my having more than somebody else, but don’t ask me to explain how or why because it’s just a fuzzy, uneasy feeling on my part. Because I have something, I feel obligated to have less of it. It makes me feel good to give it away because doing so expunges me of the sin of having it in the first place. Now I’m a good guy, am I not?”

It was apparent to me how deeply ingrained this mindset has become when I visited the gravesite of John D. Rockefeller at Lakeview Cemetery in Cleveland a couple years ago. The wording on a nearby plaque commemorating the life of this remarkable entrepreneur implied that giving much of his fortune away was as worthy an achievement as building the great international enterprise, Standard Oil, that produced it in the first place. The history books most kids learn from these days go a step further. They routinely criticize people like Rockefeller for the wealth they created and for the profit motive, or self-interest, that played a part in their creating it, while lauding them for relieving themselves of the money.

More than once, philanthropists have bestowed contributions on my organization and explained they were “giving something back.” They meant that by giving to us, they were paying some debt to society at large. It turns out that, with few exceptions, these philanthropists really had not done anything wrong.

They made money in their lives, to be sure, but they didn’t steal it. They took risks they didn’t have to. They invested their own funds, or what they first borrowed and later paid back with interest. They created jobs, paid market wages to willing workers, and thereby generated livelihoods for thousands of families. They invented things that didn’t exist before, some of which saved lives and made us healthier. They manufactured products and provided services, for which they asked and received market prices.

They had willing and eager customers who came back for more again and again. They had stockholders to whom they had to offer favorable returns. They also had competitors and had to stay on top of things or lose out to them. They didn’t use force to get where they got; they relied on free exchange and voluntary contract. They paid their bills and debts in full. And every year they donated some of their profits to lots of community charities that no law required them to support. Not a one of them that I know ever did any jail time for anything.

So how is it that anybody can add all that up and still feel guilty? I suspect that if they are genuinely guilty of anything, it’s allowing themselves to be intimidated by the losers and the envious of the world, the people who are in the redistribution business either because they don’t know how to create anything or because they simply choose the easy way out. They just take what they want or hire politicians to take it for them.

Or like a few in the clergy who think that wealth is not made but simply “collected,” the redistributionists lay a guilt trip on people until they disgorge their lucre—notwithstanding the Tenth Commandment against coveting. Certainly, people of faith have an obligation to support their church, mosque, or synagogue, but that’s another matter and not at issue here.

A person who breaches a contract owes something, but it’s to the specific party on the other side of the deal. Steal someone else’s property and you owe it to the person you stole it from, not society, to give it back. Those obligations are real and they stem from a voluntary agreement in the first instance or from an immoral act of theft in the second. This business of “giving something back” simply because you earned it amounts to manufacturing mystical obligations where none exist. It turns the whole concept of “debt” on its head. To give it “back” means it wasn’t yours in the first place, but the creation of wealth through private initiative and voluntary exchange does not involve the expropriation of anyone’s rightful property.

How can it possibly be otherwise? By what rational measure does a successful person in a free market, who has made good on all his debts and obligations in the traditional sense, owe something further to a nebulous entity called “society”? If Entrepreneur X earns $1 billion and Entrepreneur Y earns $2 billion, would it make sense to say that Y should “give back” twice as much as X? And if so, who should decide to whom he owes it? Clearly, the whole notion of “giving something back” just because you have it is built on intellectual quicksand.

Successful people who earn their wealth through free and peaceful exchange may choose to give some of it away, but they’d be no less moral and no less debt-free if they gave away nothing. It cheapens the powerful charitable impulse that all but a few people possess to suggest that charity is equivalent to debt service or that it should be motivated by any degree of guilt or self-flagellation.

A partial list of those who honestly do have an obligation to give something back would include bank robbers, shoplifters, scam artists, deadbeats, and politicians who “bring home the bacon.” They have good reason to feel guilt, because they’re guilty.

But if you are an exemplar of the free and entrepreneurial society, one who has truly earned and husbanded what you have and one who has done nothing to injure the lives, property, or rights of others, you are a different breed altogether. When you give, you should do so because of the personal satisfaction you derive from supporting worthy causes, not because you need to salve a guilty conscience.

Lawrence W. Reed

President

Foundation for Economic Education

Summary

- The innocent-sounding phrase, “I want to give back,” far too often implies guilt for having been productive or successful.

- If you earned your wealth through free and voluntary exchange, don’t let others get away with making you feel guilty just because you have it.

- The people who really should “give it back” are those to whom it doesn’t belong or who took it from others in the first place.

- For further information, see:

“On Giving Back” by George C. Leef: http://tinyurl.com/lqd3lo6

“Give Up on Giving Back?” by Sandy Ikeda: http://tinyurl.com/or7jhh3

“Giving Back” by Steven Horwitz: http://tinyurl.com/pwqjqzw

Lawrence W. (“Larry”) Reed became president of FEE in 2008 after serving as chairman of its board of trustees in the 1990s and both writing and speaking for FEE since the late 1970s. Prior to becoming FEE’s president, he served for 20 years as president of the Mackinac Center for Public Policy in Midland, Michigan. He also taught economics full-time from 1977 to 1984 at Northwood University in Michigan and chaired its department of economics from 1982 to 1984.

EDITORS NOTE: Versions of this essay have previously appeared in FEE’s journal, The Freeman, under the title, “Who Owes What to Whom?”

The Foundation for Economic Education (FEE) is proud to partner with Young America’s Foundation (YAF) to produce “Clichés of Progressivism,” a series of insightful commentaries covering topics of free enterprise, income inequality, and limited government.

Our society is inundated with half-truths and misconceptions about the economy in general and free enterprise in particular. The “Clichés of Progressivism” series is meant to equip students with the arguments necessary to inform debate and correct the record where bias and errors abound.

The antecedents to this collection are two classic FEE publications that YAF helped distribute in the past: Clichés of Politics, published in 1994, and the more influential Clichés of Socialism, which made its first appearance in 1962. Indeed, this new collection will contain a number of essays from those two earlier works, updated for the present day where necessary. Other entries first appeared in some version in FEE’s journal, The Freeman. Still others are brand new, never having appeared in print anywhere. They will be published weekly on the websites of both YAF and FEE: www.yaf.org and www.FEE.org until the series runs its course. A book will then be released in 2015 featuring the best of the essays, and will be widely distributed in schools and on college campuses.

See the index of the published chapters here.

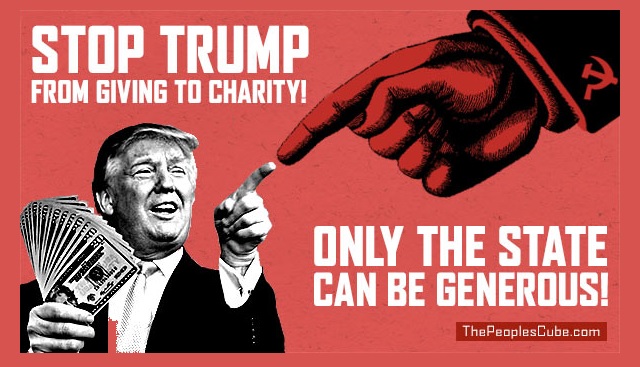

EDITORS NOTE: This political satire by Hammer and Loupe originally appeared on The Peoples Cube.

EDITORS NOTE: This political satire by Hammer and Loupe originally appeared on The Peoples Cube.