8 Ideas That Will Teach You to Think Like an Economist

Sound economic thinking is vital for a prosperous future.

Economics is the study of human action—the choices people make in a world of scarcity. Scarcity means that people have unlimited wants but we live in a world of limited resources. Because of this fact people have to make choices, and choices imply trade-offs. The choices people make are influenced by the incentives they face and those incentives are shaped by the institutions—rules of the game—under which people live and interact with others.

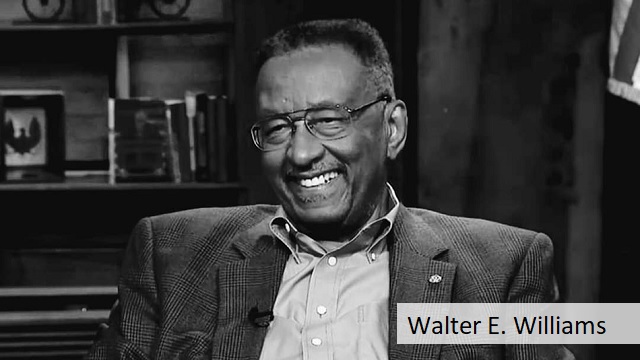

The Foundation for Economic Education has published some excellent essays on the economic way of thinking and basic concepts (“The Economic Way of Thinking” by Ronald Nash and “Economics for the Citizen” by Walter E. Williams).

In this essay, I will explain eight ideas and give examples of the economic way of thinking.

1. TANSTAAFL: Know the Difference Between Price and Cost

We often hear how wonderful certain countries are because they provide “free healthcare” or “free education.” Many will also say “I got it for free” because they didn’t pay with money.

The error lies in not understanding the difference between price and cost. For example, people usually say, “The Starbucks latte cost me five dollars” or, “The movie ticket cost me fifteen dollars.” Cost in economics means what you give up or sacrifice. In these examples, the prices were $5 and $15. But the cost of the latte was perhaps the sandwich one could have purchased instead with that same $5, and the cost of the movie was perhaps the three lattes one could have purchased instead with that same $15.

Labeling healthcare and education “free” is not just wrong—”there’s no such thing as a free lunch”—it’s also misleading. As my former professor Walter E. Williams would say, “Unless you believe in Santa Claus or the Tooth Fairy, the money has to come from somewhere.” You might not get a medical bill in those countries but you have more taken out of your paycheck (i.e., taxes) and you might have to wait much longer to get that test or have that “minor” (from the bureaucrats’ perspective) surgery. You pay with either money or time, but either way, you pay! Taxes are also used to pay for public schools, which is yet another example of how people call something “free” when it is not.

There’s a difference between zero price and zero cost. There could be a zero price ($0), but there’s never a zero cost. Therefore, don’t swear anymore by using the “F” word!

2. Actions Matter More Than Statements

“Actions speak louder than words,” is a well-known idiom. Humans act, and the act of choice tells us something. Consider this example: A person walks into an Apple store and sees the price of the latest iPhone and angrily mumbles, “What a rip off” but still proceeds to purchase that phone.

When one does something voluntarily, it demonstrates their true preference at the time. Assuming that individuals are self-interested and will ex ante (looking forward in time) subjectively weigh the cost and benefit of an action, and, also assuming it’s not a right to have the private property of another (i.e., Apple’s iPhone), then when a person walks into an Apple store and buys the new iPhone, the individual obviously expects to be better off in some way at that moment. To say that Apple “took advantage” of the willing customer would be nonsense since Apple, or any private business, cannot force people to buy their product. It’s one thing to say something, but the proof is in the act of choice.

3. Sunk Cost Fallacy: Don’t Cry Over Spilt Milk

“Don’t cry over spilt milk” means what’s done is done. The only costs that should come into our decision-making are future opportunity costs. Past costs are “sunk.” The typical example to explain the sunk cost fallacy is the movie example. You spend $15 to see a movie and an hour into this three-hour movie you realize that it’s horrible and will only get worse. However, your feeling is that you should stay and get your money’s worth. That is bad economic thinking. The $15 is gone so don’t lose the next two hours of your valuable time—get up and leave.

Most of us know people who were (are) in a horrible relationship or dating the wrong type of person (perhaps this applies to you). But the feeling of “I’ve already spent two years of my life with this person” can lead to a bad decision. Many end up marrying the person in order to justify the investment of time.

No offense to Beyoncé, but if you like yourself, then perhaps don’t let that person “put a ring on it”! Don’t lose the next two years of precious time. It’s better to be single than in a bad relationship (but that’s for another essay).

4. Tradeoffs: Learn to Think at the Margin

The optimal or efficient level of pollution is not zero. The optimal number of traffic deaths or sports injuries also is probably not zero. The optimal number of people getting a virus is not zero. The optimal level of safety is not perfect safety. Does this sound strange or harsh? Well, if you want to do a cross country road trip and not walk or ride a bike, or if you want to enjoy playing or watching sports, and if you want to physically interact with others, then it is clear that the optimal level of pollution, deaths, injuries, and people getting a virus is actually greater than zero. The optimal level of safety is less than perfect safety. Nothing is free including more safety—trade-offs are always involved because there is always an opportunity cost when we do something, even things like travel, play sports, or interact with others.

Incremental decision-making is what economists call thinking at the margin. Marginal means the one additional or extra unit. Every time we make a decision it’s as if we are calculating the marginal benefit (the benefit of one more unit) and the marginal cost (what would be given up to acquire one more unit) of the action. The economic way of thinking says something should be done until the marginal benefit (MB) equals the marginal cost (MC). There’s also a concept known as the law of diminishing marginal utility—each additional unit gives less and less utility or benefit.

We want clean air so that our eyes aren’t irritated when we go outside and our lungs don’t burn when we take a breath. However, if the desire is perfectly clean air this would mean no more cars, no planes, no boats or ships, and no trains (some would actually desire this situation, at least theoretically). This would impose tremendous costs on society.

Let’s look at it another way. If I snapped my fingers and made the Pacific Ocean perfectly clean but then put one drop of oil somewhere in the ocean unbeknownst to everyone else, would it be worth it to spend money, time and other resources to hunt down that one drop of oil? The marginal benefit of finding and removing one drop of oil in the quintillions of gallons of water would be less than the marginal cost. In plain English, it’s not worth it. Again, the optimal level of pollution is some, not zero.

When it comes to studying, practicing a sport or musical instrument, or dating someone before marrying them, you might think, “The more time, the better.” I am a literal person so if I told my students, “The more you study the better,” this would mean they would never eat, drink, sleep, or spend time with family and friends. But common sense says that after studying for a certain amount of time most students will say, “I get it” or simply “time to move on.” Why waste more time studying?

Also, if you are in a place in your life where you are considering marriage, then the point of dating is to acquire information about the other person so that you can make a good decision. Ultimately, you come to a point where you have enough information to propose, accept a proposal, or break up with this person. When I proposed to my wife, I did not have perfect information about her, but my information was good enough. Sure, one more month of dating would have given me some marginal benefit in terms of additional information about her, but I came to a point where I had enough information—where MB=MC.

“Good enough is good enough” is what economists mean by doing something until the marginal benefit equals the marginal cost. The MB=MC rule implies that the “more is better” thinking is not optimal. One aspirin from the bottle can help your headache but it’s dangerous to think, “Well, if one is good, the whole bottle is better.” Yes, your headache will be gone but so will you.

5. Comparative Advantage: Ability to Do Something Does Not Mean One Should

In a standard economics class, students are taught absolute advantage and comparative advantage. The former means being able to produce more than another with the same amount of resources or using fewer resources to produce an output. The latter means being able to do something at a lower opportunity cost than another.

Because there’s always an opportunity cost when doing something, sometimes it is advantageous to pay someone else to do something even if we have the knowledge and skills to do it ourselves. This also has applications to trade policy. Just because the United States (actually individuals in the United States) can produce certain products does not mean we should. It’s ok if not everything we buy says “Made in USA” because if the government tries to “protect American jobs” and begins imposing tariffs and quotas, we are not actually saving American jobs. It’s more correct to say we are saving particular jobs at the expense of other American jobs. Of course, good politics and good economics often go in different directions.

6. Supply and Demand: Understand How Prices Work

The complaint that businesses can charge “whatever they want” is nonsense. For example, why is it that movie theaters only charge $8 for popcorn and not $8,000 or $8,000,000 if they can supposedly charge whatever they want? There are two sides to a market transaction, and it’s this interaction of sellers and buyers that determines the price. What’s interesting is that many times the same people complaining are the ones making noise eating that popcorn during the movie.

7. Fixed Pie Fallacy: Voluntary Exchange Is Win-Win That Creates a Bigger Pie

Entrepreneurs become wealthy if they create a product or service that provides value for a large number of people. Unless the entrepreneurs received special privileges from the government, they didn’t forcibly take money from their customers.

The anger directed at “the rich” is based on the fallacy of thinking the economy is a fixed-size pie. In other words, those who criticize the “filthy rich” believe that they took a piece that was too big, leaving less pie for the rest of us regular folks. The reality is that these entrepreneurs baked a bigger pie. They benefited, but so did we!

In a business transaction, exchanges are voluntary, and voluntary trade is a win-win situation. The entrepreneur wins (as well as the employees he or she hires) and the customers win.

8. Good Intentions Fallacy: Don’t Forget about Unseen Costs

Intentions and results are not always the same thing. The economic way of thinking teaches us to consider possible unintended consequences of our own actions or the actions of politicians. Just because something sounds good or feels right does not mean a certain goal will be achieved. In fact, the very problem that is being addressed can become worse.

Sound economic thinking also removes one’s blinders. The effects of a policy on all groups are considered, not just one group. This helps individuals to see through politicians’ claims that a policy will save American jobs when in reality only some special-interest group will benefit at the expense of other Americans. When politicians confiscate money (i.e., taxes) to build sports stadiums using the “it will create jobs” argument, the mistake is to focus on the jobs seen and neglecting the unseen—the opportunity cost of those tax dollars.

Conclusion

There is so much more to say about this subject called economics and there are many more examples of the economic way of thinking that I could have included. Some characterize economics as applied common sense; yet, economics also gives us counterintuitive insights.

This is the power and beauty of economics

AUTHOR

Ninos P. Malek

Ninos P. Malek is an Economics professor at De Anza College in Cupertino, California and a Lecturer at San Jose State University in San Jose, California. He teaches principles of macroeconomics, principles of microeconomics, economics of social issues, and intermediate microeconomics. His previous experience also includes teaching introductory economics at George Mason University.

EDITORS NOTE: This FEE column is republished with permission. ©All rights reserved.