Why are we so rich? Who are “we”? Have our riches corrupted us?

“The Bourgeois Era,” a series of three l-o-n-g books just completed — thank God — answers:

- first, in The Bourgeois Virtues: Ethics for an Age of Commerce (2006), that the commercial bourgeoisie — the middle class of traders, dealers, inventors, and managers — is on the whole, contrary to the conviction of the “clerisy” of artists and intellectuals after 1848, pretty good. Not bad.

- second, in Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can’t Explain the Modern World (2010), that the modern world was made not by the usual material causes, such as coal or thrift or capital or exports or imperialism or good property rights or even good science, all of which have been widespread in other cultures and at other times. It was caused by very many technical and some few institutional ideas among a uniquely revalued bourgeoisie — on a large scale at first peculiar to northwestern Europe, and indeed peculiar from the sixteenth century to the Low Countries;

- and third, in Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World (2016), that a novel way of looking at the virtues and at bettering ideas arose in northwestern Europe from a novel liberty and dignity enjoyed by all commoners, among them the bourgeoisie, and from a startling revaluation starting in Holland by the society as a whole of the trading and betterment in which the bourgeoisie specialized.The revaluation, called “liberalism,” in turn derived not from some ancient superiority of the Europeans but from egalitarian accidents in their politics from 1517–1789. That is, what mattered were two levels of ideas — the ideas in the heads of entrepreneurs for the betterments themselves (the electric motor, the airplane, the stock market); and the ideas in the society at large about the businesspeople and their betterments (in a word, that liberalism). What were not causal were the conventional factors of accumulated capital and institutional change. They happened, but they were largely dependent on betterment and liberalism.

The upshot since 1800 has been a gigantic improvement for the poor, yielding equality of real comfort in health and housing, such as for many of your ancestors and mine, and a promise now being fulfilled of the same result worldwide — a Great Enrichment for even the poorest among us.

These are controversial claims. They are, you see, optimistic. Many of the left, such as my friend the economist and former finance minister of Greece, Yanis Varoufakis, or the French economist Thomas Piketty, and some on the right, such as my friend the American economist Tyler Cowen, believe we are doomed.

Yanis thinks that wealth is caused by imperial sums of capital sloshing around the world economy, and thinks in a Marxist and Keynesian way that the economy is like a balloon, puffed up by consumption, and about to leak. I think that the economy is like a machine making sausage, and if Greece or Europe want to get more wealth they need to make the machine work better — honoring enterprise, for example, and letting people work when they want to.

Piketty thinks that the rich get richer, always, and that the rest of us stagnate. I think it’s not true, even in his own statistics, and certainly not in the long run, and that what has mainly happened in the past two centuries is that the sausage machine has got tremendously more productive, benefiting mainly the poor.

Tyler thinks that improvements in the sausage machine are over. I think that if Tyler were so smart (and he is very smart), he would be rich, and anyway there is little evidence of technological stagnation, and anyway for at least the next century, the poor of the non-Western world will be catching up, enriching us all with their own betterments of the sausage machine.

In other words, I do not think we are doomed. I see over the next century a world enrichment both materially and spiritually that will give the wretched of the earth the lives of a present-day, bourgeois Dutch person.

For reasons I do not entirely understand, the clerisy after 1848 turned toward nationalism and socialism, and against liberalism. It came also to delight in an ever expanding list of pessimisms about the way we live now in our approximately liberal societies, from the lack of temperance among the poor to an excess of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Anti-liberal utopias believed to offset the pessimisms have been popular among the clerisy. Its pessimistic and utopian books have sold millions.

But the twentieth-century experiments of nationalism and socialism, of syndicalism in factories and central planning for investment, of proliferating regulation for imagined but not factually documented imperfections in the market, did not work. And most of the pessimisms about how we live now have proven to be mistaken.

It is a puzzle. Perhaps you yourself still believe in nationalism or socialism or proliferating regulation. And perhaps you are in the grip of pessimism about growth or consumerism or the environment or inequality. Please, for the good of the wretched of the earth, reconsider. The trilogy chronicles, explains, and defends what made us rich — the system we have had since 1800 or 1848, usually but misleadingly called modern “capitalism.”

The system should rather be called “technological and institutional betterment at a frenetic pace, tested by unforced exchange among all the parties involved.” Or “fantastically successful liberalism, in the old European sense, applied to trade and politics, as it was applied also to science and music and painting and literature.” The simplest version is “trade-tested progress.”

Many humans, in short, are now stunningly better off than their ancestors were in 1800. And the rest of humanity shows every sign of joining the enrichment. A crucial point is that the greatly enriched world cannot be explained in any deep way by the accumulation of capital, as economists from Adam Smith through Karl Marx to Varoufakis, Piketty, and Cowen have on the contrary believed, and as the very word “capitalism” seems to imply.

The word embodies a scientific mistake. Our riches did not come from piling brick on brick, or piling university degree on university degree, or bank balance on bank balance, but from piling idea on idea. The bricks, degrees, and bank balances — the capital accumulations — were of course necessary. But so were a labor force and liquid water and the arrow of time.

Oxygen is necessary for a fire. But it would be at least unhelpful to explain the Chicago Fire of October 8-10, 1871, by the presence of oxygen in the earth’s atmosphere. Better: a long dry spell, the city’s wooden buildings, a strong wind from the southwest, and, if you disdain Irish immigrants, Mrs. O’Leary’s cow.

The modern world cannot be explained, I show in the second volume, Bourgeois Dignity, by routine brick-piling, such as the Indian Ocean trade, English banking, canals, the British savings rate, the Atlantic slave trade, natural resources, the enclosure movement, the exploitation of workers in satanic mills, or the accumulation in European cities of capital, whether physical or human. Such routines are too common in world history and too feeble in quantitative oomph to explain the thirty- or hundredfold enrichment per person unique to the past two centuries.

Hear again that last, crucial, astonishing fact, discovered by economic historians over the past few decades. It is: in the two centuries after 1800 the trade-tested goods and services available to the average person in Sweden or Taiwan rose by a factor of 30 or 100. Not 100 percent, understand — a mere doubling — but in its highest estimate a factor of 100, nearly 10,000 percent, and at least a factor of 30, or 2,900 percent.

The Great Enrichment of the past two centuries has dwarfed any of the previous and temporary enrichments. Explaining it is the central scientific task of economics and economic history, and it matters for any other sort of social science or recent history. What explains it? The causes were not (to pick from the apparently inexhaustible list of materialist factors promoted by this or that economist or economic historian) coal, thrift, transport, high male wages, low female and child wages, surplus value, human capital, geography, railways, institutions, infrastructure, nationalism, the quickening of commerce, the late medieval run-up, Renaissance individualism, the First Divergence, the Black Death, American silver, the original accumulation of capital, piracy, empire, eugenic improvement, the mathematization of celestial mechanics, technical education, or a perfection of property rights.

Such conditions had been routine in a dozen of the leading organized societies of Eurasia, from ancient Egypt and China down to Tokugawa Japan and the Ottoman Empire, and not unknown in Meso-America and the Andes. Routines cannot account for the strangest secular event in human history, which began with bourgeois dignity in Holland after 1600, gathered up its tools for betterment in England after 1700, and burst on northwestern Europe and then the world after 1800.

The modern world was made by a slow-motion revolution in ethical convictions about virtues and vices, in particular by a much higher level than in earlier times of toleration for trade-tested progress — letting people make mutually advantageous deals, and even admiring them for doing so, and especially admiring them when Steve Jobs-like they imagine betterments.

Note: the crux was not psychology — Max Weber had claimed in 1905 that it was — but sociology. Toleration for free trade and honored betterment was advocated first by the bourgeoisie itself, then more consequentially by the clerisy, which for a century before 1848 admired economic liberty and bourgeois dignity, and in aid of the project was willing to pledge its life, fortune, and sacred honor.

After 1848 in places like the United States and Holland and Japan, the bulk of ordinary people came slowly to agree. By then, however much of the avant garde of the clerisy worldwide had turned decisively against the bourgeoisie, on the road to twentieth-century fascism and communism.

Yet in the luckier countries, such as Norway or Australia, the bourgeoisie was for the first time judged by many people to be acceptably honest, and was in fact acceptably honest, under new social and familial pressures. By 1900, and more so by 2000, the Bourgeois Revaluation had made most people in quite a few places, from Syracuse to Singapore, very rich and pretty good.

I have to admit that “my” explanation is embarrassingly, pathetically unoriginal. It is merely the economic and historical realization in actual economies and actual economic histories of eighteenth-century liberal thought. But that, after all, is just what the clerisy after 1848 so sadly mislaid, and what the subsequent history proved to be profoundly correct. Liberty and dignity for ordinary people made us rich, in every meaning of the word.

The change, the Bourgeois Revaluation, was the coming of a business-respecting civilization, an acceptance of the Bourgeois Deal: “Let me make money in the first act, and by the third act I will make you all rich.”

Much of the elite, and then also much of the non-elite of northwestern Europe and its offshoots, came to accept or even admire the values of trade and betterment. Or at the least the polity did not attempt to block such values, as it had done energetically in earlier times. Especially it did not do so in the new United States. Then likewise, the elites and then the common people in more of the world followed, including now, startlingly, China and India. They undertook to respect—or at least not to utterly despise and overtax and stupidly regulate—the bourgeoisie.

Why, then, the Bourgeois Revaluation that after made for trade-tested betterment, the Great Enrichment? The answer is the surprising, black-swan luck of northwestern Europe’s reaction to the turmoil of the early modern — the coincidence in northwestern Europe of successful Reading, Reformation, Revolt, and Revolution: “the Four Rs,” if you please. The dice were rolled by Gutenberg, Luther, Willem van Oranje, and Oliver Cromwell. By a lucky chance for England their payoffs were deposited in that formerly inconsequential nation in a pile late in the seventeenth century.

None of the Four Rs had deep English or European causes. All could have rolled the other way. They were bizarre and unpredictable. In 1400 or even in 1600 a canny observer would have bet on an industrial revolution and a great enrichment — if she could have imagined such freakish events — in technologically advanced China, or in the vigorous Ottoman Empire. Not in backward, quarrelsome Europe.

A result of Reading, Reformation, Revolt, and Revolution was a fifth R, a crucial Revaluation of the bourgeoisie, first in Holland and then in Britain. The Revaluation was part of an R-caused, egalitarian reappraisal of ordinary people. I retail here the evidence that hierarchy — as, for instance, in St. Paul’s and Martin Luther’s conviction that the political authorities that exist have been instituted by God — began slowly and partially to break down.

The cause of the bourgeois betterments, that is, was an economic liberation and a sociological dignifying of, say, a barber and wig-maker of Bolton, son of a tailor, messing about with spinning machines, who died in 1792 as Sir Richard Arkwright, possessed of one of the largest bourgeois fortunes in England. The Industrial Revolution and especially the Great Enrichment came from liberating commoners from compelled service to a hereditary elite, such as the noble lord in the castle, or compelled obedience to a state functionary, such as the economic planner in the city hall. And it came from according honor to the formerly despised of Bolton — or of Ōsaka, or of Lake Wobegon — commoners exercising their liberty to relocate a factory or invent airbrakes.

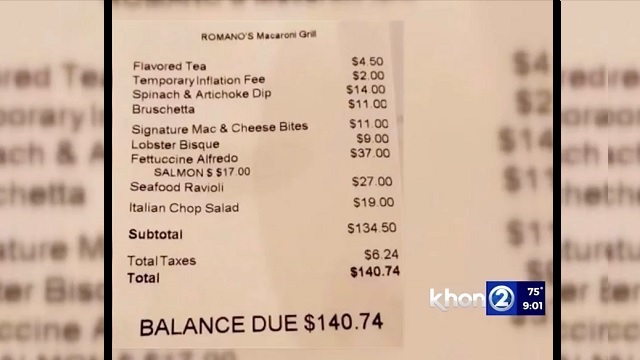

Not everyone accepted the Bourgeois Deal, even in the United States. There’s the worry: it’s not complete, and can be undermined by hostile attitudes and clumsy regulations. In Chicago you need a $300 business license to start a little repair service for sewing machines, but you can’t do it in your home because of zoning, arranged politically by big retailers. Likewise in Rotterdam, worse.

Antibourgeois attitudes survive even in bourgeois cities like London and New York and Milan, expressed around neo-aristocratic dinner tables and in neo-priestly editorial meetings. A journalist in Sweden noted recently that when the Swedish government recommended two centimeters of toothpaste on one’s brush no journalist complained:

[The] journalists . . . take great professional pride in treating with the utmost skepticism a press release or some new report from any commercial entity. And rightly so. But the big mystery is why similar output is treated differently just because it is from a government organization. It’s not hard to imagine the media’s response if Colgate put out a press release telling the general public to use at least two centimeters of toothpaste twice every day.

The bourgeoisie is far from ethically blameless. The newly tolerated bourgeoisie has regularly tried to set itself up as a new aristocracy to be protected by the state, as Adam Smith and Karl Marx predicted it would. And anyway even in the embourgeoisfying lands on the shores of the North Sea, the old hierarchy based on birth or clerical rank did not simply disappear on January 1, 1700.

Tales of pre- or antibourgeois life strangely dominated the high and low art of the Bourgeois Era. Flaubert’s and Hemingway’s novels, D’Annunzio’s and Eliot’s poetry, Eisenstein’s and Pasolini’s films, not to speak of a rich undergrowth of cowboy movies and spy novels, all celebrate peasant/proletariat or aristocratic values.

A hard coming we bourgeois have had of it. A unique liberalism was what freed the betterment of equals, starting in Holland in 1585, and in England and New England a century later. Betterment came largely out of a change in the ethical rhetoric of the economy, especially about the bourgeoisie and its projects.

You can see that “bourgeois” does not have to mean what conservatives and progressives mean by it, namely, “having a thoroughly corrupted human spirit.” The typical bourgeois was viewed by the Romantic, Scottish conservative Thomas Carlyle in 1843 as an atheist with “a deadened soul, seared with the brute Idolatry of Sense, to whom going to Hell is equivalent to not making money.”

Or from the other side, in 1996 Charles Sellers, the influential leftist historian of the United States, viewed the new respect for the bourgeoisie in America as a plague that would, between 1815 and 1846, “wrench a commodified humanity to relentless competitive effort and poison the more affective and altruistic relations of social reproduction that outweigh material accumulation for most human beings.”

Contrary to Carlyle and Sellers, however, bourgeois life is in fact mainly cooperative and altruistic, and when competitive it is good for the poorest among us. We should have more of it. The Bourgeois Deal does not imply, however, that one needs to be fond of the vice of greed, or needs to think that greed suffices for an economic ethic. Such a Machiavellian theory, “greed is good,” has undermined ethical thinking about the Bourgeois Era. It has especially done so during the past three decades in smart-aleck hangouts such as Wall Street or the Department of Economics.

Prudence is a great virtue among the seven principal virtues. But greed is the sin of prudence only — namely, the admitted virtue of prudence when it is not balanced by the other six, becoming therefore a vice. That is the central point of Deirdre McCloskey, The Bourgeois Virtues, of 2006, or for that matter of Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, of 1759 (so original and up-to-date is McCloskey).

Nor has the Bourgeois Era led in fact to a poisoning of the virtues. In a collection of mini-essays asking “Does the Free Market Corrode Moral Character?” the political theorist Michael Walzer replied “Of course it does.” But then he wisely adds that any social system corrodes one or another virtue. That the Bourgeois Era surely has tempted people into thinking that greed is good, wrote Walzer, “isn’t itself an argument against the free market. Think about the ways democratic politics also corrodes moral character. Competition for political power puts people under great pressure . . . to shout lies at public meeting, to make promises they can’t keep.”

Or think about the ways even a mild socialism puts people under great pressure to commit the sins of envy or state-enforced greed or violence or environmental imprudence. Or think about the ways the alleged affective and altruistic relations of social reproduction in America before the alleged commercial revolution put people under great pressure to obey their husbands in all things and to hang troublesome Quakers and Anabaptists.

That is to say, any social system, if it is not to dissolve into a war of all against all, needs ethics internalized by its participants. It must have some device — preaching, movies, the press, child raising, the state — to slow down the corrosion of moral character, at any rate by the standard the society sets. The Bourgeois Era has set a higher social standard than others, abolishing slavery and giving votes to women and the poor.

For further progress Walzer the communitarian puts his trust in an old conservative argument, an ethical education arising from good-intentioned laws. One might doubt that a state strong enough to enforce such laws would remain uncorrupted for long, at any rate outside of northern Europe. In any case, contrary to a common opinion since 1848 the arrival of a bourgeois, business-respecting civilization did not corrupt the human spirit, despite temptations. Mostly in fact it elevated the human spirit.

Walzer is right to complain that “the arrogance of the economic elite these last few decades has been astonishing.” So it has. But the arrogance comes from the smartaleck theory that greed is good, not from the moralized economy of trade and betterment that Smith and Mill and later economists saw around them, and which continues even now to spread.

The Bourgeois Era did not thrust aside, as Sellers the historian elsewhere claims in rhapsodizing about the world we have lost, lives “of enduring human values of family, trust, cooperation, love, and equality.” Good lives such as these can be and actually are lived on a gigantic scale in the modern, bourgeois town. In Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country, John Kumalo, from a village in Natal, and now a big man in Johannesburg, says, “I do not say we are free here.” A black man under apartheid in South Africa in 1948 could hardly say so. “But at least I am free of the chief. At least I am free of an old and ignorant man.”

The Revaluation, in short, came out of a rhetoric — what the Dutch economist Arjo Klamer calls the “conversation” — that would, and will, enrich the world. We are not doomed. If we have a sensible and fact-based conversation about economics and economic history and politics we will do pretty well, for Rio and Rotterdam and the rest.

Deirdre N. McCloskey

Deirdre N. McCloskey

Deirdre Nansen McCloskey taught at the University of Illinois at Chicago from 2000 to 2015 in economics, history, English, and communication. A well-known economist and historian and rhetorician, she has written 17 books and around 400 scholarly pieces on topics ranging from technical economics and statistical theory to transgender advocacy and the ethics of the bourgeois virtues. Her latest book, out in January 2016 from the University of Chicago Press—Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World—argues for an “ideational” explanation for the Great Enrichment 1800 to the present.

As you might suspect, it would be an understatement to say this puts me in the belly of the beast (for

As you might suspect, it would be an understatement to say this puts me in the belly of the beast (for  I’m not joking. I

I’m not joking. I  Most of the discussions focused on how tax laws, tax treaties, and tax agreements can and should be altered to extract more money from the business community. Participants occasionally groused about tax evasion, but the real focus was on ways to curtail tax avoidance. This is noteworthy because it confirms my point that the anti-tax competition work of international bureaucracies is guided by a desire to

Most of the discussions focused on how tax laws, tax treaties, and tax agreements can and should be altered to extract more money from the business community. Participants occasionally groused about tax evasion, but the real focus was on ways to curtail tax avoidance. This is noteworthy because it confirms my point that the anti-tax competition work of international bureaucracies is guided by a desire to