John Mackey: ‘Capitalism Is the Greatest Thing Mankind Has Ever Done’

The Whole Foods founder offered a clear message on capitalism at LibertyCON in Miami, where five hundred delegates from 50 countries recently gathered.

On October 14, LibertyCON kicked off with an interview between Students for Liberty CEO Wolf von Laer and John Mackey, founder of Whole Foods Market.

Mackey studied philosophy and religion for several semesters while working part-time at a vegetarian consumer cooperative. In 1978, he and his girlfriend founded a vegetarian supermarket, SaferWay, which evolved into Whole Foods Market two years later through a merger. He recounted how, after starting the company, he initially lived on $200 a month, and since he had no place to live, he and his girlfriend slept in the store. Since there was no shower, they had to wash in the sink. But he has fond memories of those days: He was in love, starting the business was a great adventure, and he didn’t actually need money privately. Later, he became very wealthy, taking the company public on the NASDAQ technology exchange and, in 2017, it was acquired by Amazon for $13.7 billion.

Today, Whole Foods operates more than 500 stores in the US, Canada, and the UK.

Capitalist, Vegan, & Animal Rights Activist

Whole Foods was the first grocery chain to commit to animal welfare. Mackey was influenced by animal rights activist Lauren Ornelas, who criticized Whole Foods’ animal welfare standards at a shareholder meeting in 2003. Mackey gave Ornelas his email address, and they corresponded on the issue of how the company treated ducks in particular. Mackey became concerned with the problems associated with factory farming and decided to switch to a mostly vegetarian diet that included only eggs from his own chickens. Since 2006, he has been living on an exclusively plant-based diet. He is an advocate of more humane animal treatment, a vegetarian, and an enthusiastic fan of capitalism—which I like, because I am all of those things myself.

To say Mackey is a proponent of free markets is an understatement.

“Capitalism is the greatest thing that mankind has ever done,” Mackey declared at the event.

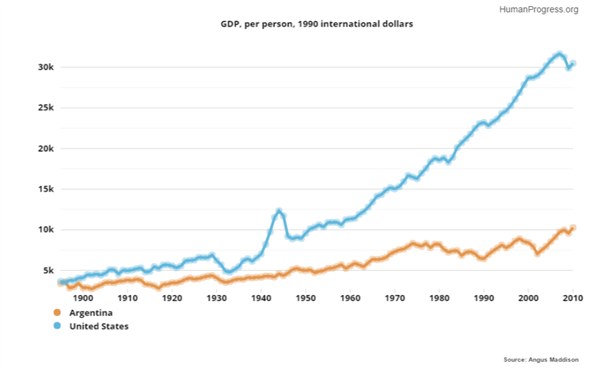

The number of people living in extreme poverty, he reminds us, has dropped from about 90 percent to less than 10 percent since the capitalist era began 200 years ago.

Mackey’s support of capitalism inspired him to write a book on the subject titled Conscious Capitalism, but it has not been without consequences. He triggered a flurry of negative reaction when he wrote an article against Obamacare that was published by the Wall Street Journal in August 2009. He did not only offer criticism, he also made ten suggestions on how to reform America’s ailing healthcare system. But his solution was not more government – as with Obama – but more market, which prompted left-wing groups to organize boycotts of his businesses.

Wolf von Laer pays tribute to the modest, soft-spoken entrepreneur for his courage in taking political positions. But Mackey himself says he would no longer write such a political article after his experience in 2009, because the response to it was so damaging to his business. That’s how it is today, and not only in the United States: Political statements from business people are only tolerated if they are critical of capitalism or “woke.” Otherwise, there is the threat of negative reaction and boycotts, as was the case against Whole Foods.

“Cancel Culture” is the name given to this anti-culture, which is nothing less than an all-out attack on freedom of expression.

Drug Legalization

Libertarians are caught between two stools. By European standards, they combine both right-wing and left-wing policy positions. On the one hand, they are enthusiastic supporters of capitalism and stridently oppose socialism, the welfare state, and wealth redistribution. On the other hand, they passionately support LGBTQ rights and drug legalization. The drug issue marks a dividing line between conservatives and libertarians, according to a panel discussion on “It’s Time to End the Drug War.”

One participant used to oppose drug legalization and now supports it for all drugs, She said the turning point for her was realizing that what she personally liked or disliked had nothing to do with what should be legal and what should be illegal. The panelists taking part in this discussion at Students for Liberty agreed that the state has lost the war against drugs, and that legalizing drugs would lead to fewer drug deaths, less crime, and more freedom and personal responsibility.

Venezuela: It Could Happen Here?

The convention moved to another topic. Why are more and more countries in Latin America sliding into socialism? Daniel DiMartino is a Venezuelan who fled the socialist country – along with a quarter of the population. He has now lived in the United States for six years and speaks of an “epidemic of envy” in Latin America. But he also criticizes conservative governments who, when in power, have not seized the opportunity to introduce the kind of radical free-market reforms that truly change people’s lives. He cites Maurico Macri in Argentina as an example.

Martha Bueno, whose parents fled Cuba and who now lives in Miami, warns young American supporters of socialism not to be overconfident that what happened in Venezuela could not happen in their country. As she explains, Venezuela was a democracy and had one of the highest standards of living in the world. And, she reminds us, Venezuela has the largest oil reserves in the world. She is convinced that no one ever would have believed that the socialists could run the country into the abyss, robbing it of its freedom and prosperity, in such a short space of time. But that is exactly what happened. And, she warns, it can happen here too, in the United States.

It was worth coming to Miami, to this event with so many interesting discussions. Wolf von Laer, the CEO of Students for Liberty, has succeeded in building the organization into the world’s largest network for libertarian students. The annual convention, to which fewer students can come than one would wish, partly because of the costs involved, is not actually the most important thing Students for Liberty does: that would be the thousands of events the organization holds with students around the world every year.

AUTHOR

Dr Rainer Zitelmann

Dr. Rainer Zitelmann is a historian and sociologist. He is also a world-renowned author, successful businessman, and real estate investor. Zitelmann has written more than 20 books. His books are successful all around the world, especially in China, India, and South Korea. His most recent books are The Rich in Public Opinion which was published in May 2020, and The Power of Capitalism which was published in 2019.

EDITORS NOTE: This FEE column is republished with permission. ©All rights reserved.

As you might suspect, it would be an understatement to say this puts me in the belly of the beast (for

As you might suspect, it would be an understatement to say this puts me in the belly of the beast (for  I’m not joking. I

I’m not joking. I  Most of the discussions focused on how tax laws, tax treaties, and tax agreements can and should be altered to extract more money from the business community. Participants occasionally groused about tax evasion, but the real focus was on ways to curtail tax avoidance. This is noteworthy because it confirms my point that the anti-tax competition work of international bureaucracies is guided by a desire to

Most of the discussions focused on how tax laws, tax treaties, and tax agreements can and should be altered to extract more money from the business community. Participants occasionally groused about tax evasion, but the real focus was on ways to curtail tax avoidance. This is noteworthy because it confirms my point that the anti-tax competition work of international bureaucracies is guided by a desire to