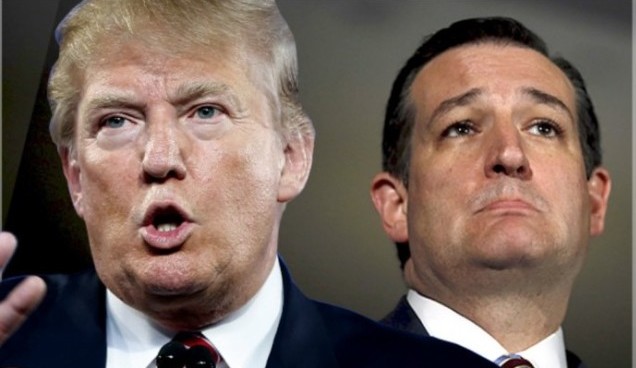

Trump, Cruz and New York Values

New York City values are going through the roof. And it’s not just real estate. A prime story the last many days has been the GOP debate dust-up between Donald Trump and Senator Ted Cruz. After the senator impugned “New York values” in an effort to call into question the businessman’s conservative bona fides, Trump responded with an impassioned defense of New Yorkers’ character. Trump won the exchange on style with rhetorical effectiveness, but, frankly, Cruz was right on substance.

This is not a commentary on whether Trump exemplifies NY values. In fact, I love most of what The Donald is saying; furthermore, while I have great respect for Cruz, the fact that no other candidate Thursday night could join Trump in supporting a halt to Muslim immigration — a common-sense measure — calls their qualifications for the presidency into question. But this isn’t a commentary on that, either, or on NY values, although I will touch on them. This article is about something far deeper.

All of us generalize. And most of us bristle at generalizations we don’t’ like — whether true or not. It’s then that we, waxing emotional, may complain about the “folly of generalization.”

Now, it may come as a shock to the critics of mine who suppose I live in West Virginia and eat chicken-fried steak, but I was born in NY and grew up in NYC — the Bronx, to be precise. And believe me, there are NY values (along with an ever decreasing number of NY virtues). Moreover, as Cruz said, most people know what they are. Trump certainly does; after all, he referenced his NY values in a 1999 interview. And while radio host and Trump supporter Michael Savage, another man I greatly respect, took exception to Cruz’ remarks, I remember when he complained on air that Vermont was ruined and became Sandersized when too many New Yorkers moved there.

What are NY values? Well, state residents elected a governor who said in 2014 that pro-life, pro-Second Amendment conservatives “have no place in the state of New York, because that’s not who New Yorkers are’”; and the Big Apple elevated to mayor Bolshevik Bill, a Marxist who honeymooned in Cuba and once raised money for the Sandinistas. You figure it out.

My real concern here, however, is not how people value New Yorkers or Cruz or Trump, but how they value generalization itself. For our refusal to properly generalize is one of the characteristic faults of our time — and a dangerous one at that.

Here’s a good example: if it’s wrong to generalize about New Yorkers because, in principle, it’s wrong to generalize, how can we then generalize about terrorists or Muslims? Doesn’t it make it harder to justify a halt to Muslim immigration if generalization is taken off the table? So some may get offended and say “Not all New Yorkers are liberals,” but this is reminiscent of liberals opposing common-sense profiling and saying “Not all Muslims are terrorists” (or “Not all terrorists are Muslim”). In point of fact, the percentage of Muslims who are terrorists is lower than the percentage of New Yorkers who are liberal, but this is irrelevant. The fact that virtually all the terrorists bedeviling us are Muslim is significant and indicates the importance of honest examination of Islamic values — which, like NY values, certainly exist.

The reality is that “not all _____ are _____” is not a valid argument against generalization, only reflective of a misunderstanding of it. If I say “Men are taller than women,” it’s silly to respond “But not all men are taller than all women!” After all, I didn’t say “all” and wasn’t implying the absence of individual variation; rather, I was referring to men and women as groups. And just as we must judge every individual as an individual and not paint everyone with the same brush, we must judge an individual group as an individual group and not paint every one with the same brush.

In fact, the only reason we can even identify groups as “groups” is that there are differences among them. And barring the rare cases in which groups are differentiated solely by location (as when dividing a class of boys into two groups placed at different tables), those differences are often neither arbitrary nor insignificant. Is location the only thing differentiating Afghans from Americans? Is location the only thing differentiating New Yorkers from Alabamans? Just as there’ll be very different government if you replace the 320 million Americans in the US with 320 million Muslims, there’ll be very different state government if you replace the 4.8 million Alabamans in Alabama with average New Yorkers.

In fairness, most NY counties without big population centers are red. “Aha,” you say, “what about those rural values in the Empire State?!” Yes, there can be sub-groups within groups, and there is a general ideological divide between the woods and the hoods. But the point is that speaking of “rural values” is a generalization, too — and a correct one.

Why does this matter? Question: who’s in closer touch with reality, someone who only understands individual variation or someone who also understands group variation? In fact, the latter is necessary for survival. Just as being able to judge individual character (as when choosing a babysitter) is important, so is being able to judge group character (related to this is being able to properly judge what faults are found mostly in a given group, even if they’re exhibited by only a minority in the group). This is especially true given that understanding group character aids in assessing individual character.

This is not synonymous with prejudice. It rather is part of profiling, which, to paraphrase Dr. Walter Williams, is a method by which we can make determinations based on scant information when the cost of obtaining more information is too high. For example, since an Israeli airport-security agent can’t spend a month living with and becoming acquainted with every traveler, he must make judgments based on group associations; thus, knowing not all Muslims are terrorists but virtually all Mideast terrorists are Muslim, he’ll scrutinize a Muslim flier more closely.

We all make such generalization/profiling-based judgments. A stranded woman motorist may refuse to roll down her window and accept aid from a young man with greasy hair who’s peppered with tattoos and body-piercings; of course, he could conceivably be well-meaning, but this is a situation where she really does have to judge the book by its cover. Likewise, she may refuse to lower her window for any man, knowing that while most men aren’t rapists, most all rapists are men. I’m not hiring a member of the Communist Party USA as a babysitter no matter how pleasant the person appears. And not all dogs bite, but it’s still a good policy to not pet strange dogs.

Doctors also must consider group characteristics, to do their patients justice. For example, understanding that Pima Indians have the world’s highest diabetes rate and that black men’s prostate-cancer rate is twice white men’s can serve as indicators for screening. And only women are routinely examined for breast cancer even though men occasionally develop the disease.

Of course, no good person wants generalization to descend into prejudice, a fault man so often exhibits. But to consequently dismiss generalization, and thus throw out of the baby with the bathwater, is much like dispensing with medical diagnostics merely because witch doctors have existed. Moreover, note that since “prejudice” is defined as “an unfavorable opinion or feeling formed beforehand or without knowledge, thought, or reason,” such an uninformed, unfavorable opinion of generalization is a prejudice itself. And it’s a prejudice that can get you killed.