Hillary Clinton’s Ideological Vortex of Power and Planning by Jeffrey A. Tucker

Just trust her. Truly, just trust her: to know precisely how much energy we ought to use, where it should come from, how it should be generated, how we should get from here to there, and the effects that her plan will have on the global — the global! — climate, not just in the near term but decades or a century from now.

If you do this, you will have embraced “science,” “reality,” “truth,” and “innovation,” and, also, “our children.” If you don’t go along, you not only reject all those good things; you are probably also a “denier,” the catch-all epithet for anyone doubtful that the brilliance of Hillary Clinton and her czars know better than the rest of humanity how to manage their energy needs into the future.

Hillary’s campaign seems designed to prove that F.A. Hayek was a prophet.

That brilliant economist spent 50 years explaining, in book after book, that the greatest danger humanity faced, now and always, was a presumption on the part of intellectuals, politicians, and bureaucrats that they know better than the emergent and evolving wisdom of social forces.

This presumption might seem like science but it is really pretense. Civilization arises from, is protected by, and advances through the dispersed knowledge of billions of individual decision makers and the institutions that arise from them.

Hayek called the issue he was investigating the knowledge problem. Society needs to know how to use scarce resources, how to navigate a world of uncertainty, how to form rules that turn struggle into peace. It is a problem solved through freedom alone. No ruler, no scientist, no intellectual can substitute for the evolving process of decentralized decision making and trial and error.

The message is bad news for people like Hillary, who is supposed to embody the ideology called “liberalism” in America. Yet it is anything but liberal. It seems to know only one way forward: more top-down control. That’s a tough sell in times when everything good so obviously comes from anything but government, and, meanwhile, governments are responsible for every failing sector from health to education to foreign wars.

But here’s the problem. People like Hillary Clinton are stuck in an ideological vortex with no way out. Government planning is their thing, and they refuse to recognize its failures. So they press on and on, even to the point of preposterous implausibility, such as the claim that government can know everything that is necessary to know in order to plan the entire energy sector with the aim of managing the climate of the world.

Economist Donald Boudreaux puts matters this way: “why should someone who cannot ensure the proper use of a single private server be trusted with the colossal power necessary to design and to oversee the remaking of a trillion-plus dollar sector of the U.S. economy (a sector, by the way, in which this person has zero experience)?”

With this presumption comes the inevitable hypocrisy.

After unveiling her plan to ration energy use and plaster the country with solar panels, Ms. Clinton boarded a private jet that uses more fuel in one flight hour than I use in a year. “The aircraft, a Dassault model Falcon 900B, burns 347 gallons of fuel per hour,” wrote the muckraker who did a public service in exposing this. “The Trump-esque transportation costs $5,850 per hour to rent, according to the website of Executive Fliteways, the company that owns it.”

Notice how rarely it is mentioned that the US military, with hundreds of bases in over a hundred countries, is the worst single polluter on the planet. If we really believe in human-caused climate change, this might be a good place to start cutting back. But no, there’s not a word about this in any of Hillary’s plans. Government gets to do what it must do. The rest of us are supposed to pay the price, bicycling to work and powering our homes with sunshine and windmills.

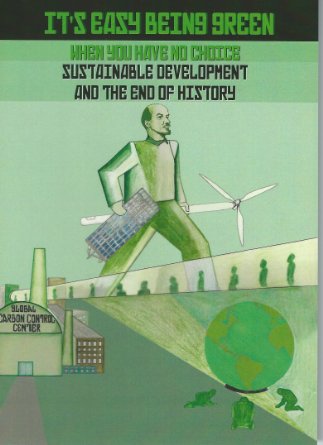

When I first read about her energy plan, my response was: Why would any self-interested politician make the need for reduced living standards a centerpiece of her campaign? After all, her speech was made in a setting piled high with bicycles (oddly reminiscent of Mao’s China), while demanding a precise path forward for energy and everything that uses it (oddly reminiscent of Lenin’s first speech after he took control of Russian economic life).

As it turns out, people aren’t that interested. Sure, most people tell pollsters that they favor renewable energy to stop climate change. You have to say that or else risk being denounced as a denier. On the other hand, it seems like very few people really care enough to forgo the benefits of modern life, which is probably what will save civilization itself from plans like hers. Note that days after release, her pompous video only had only 54K views — pathetic given her celebrity and how much money her campaign is spending, but encouraging that nobody seems to put much stock in her plan for our future.

It’s extraordinary how quickly one branch of the political class has leapt from the delicate and ever-changing science of climate monitoring to the absolute certainty that extreme and extremely specific application of government force is the way to deal with it. Writes Max Borders: “The sacralization of climate is being used as a great loophole in the rule of law, an apology for bad science (and even worse economics), and an excuse to do anything and everything to have and keep power.”

The last point is critical. Everything done in the name of public policy in our lifetimes has become a handful of dust, yielding little more than unpayable debts and unworkable programs, and leaving in its wake an apparatus of compulsion and control that robs society of its inherent genius.

What to do? Give up? That’s not an option for these people. Instead, they find a new frontier for their schemes, a new rationale to sustain a failed model of social and economic organization.

I can think of no better words of rebuke but the closing of Hayek’s Nobel speech in 1974:

If man is not to do more harm than good in his efforts to improve the social order, he will have to learn that in this, as in all other fields where essential complexity of an organized kind prevails, he cannot acquire the full knowledge which would make mastery of the events possible.

He will therefore have to use what knowledge he can achieve, not to shape the results as the craftsman shapes his handiwork, but rather to cultivate a growth by providing the appropriate environment, in the manner in which the gardener does this for his plants.

There is danger in the exuberant feeling of ever growing power which the advance of the physical sciences has engendered and which tempts man to try, “dizzy with success”, to use a characteristic phrase of early communism, to subject not only our natural but also our human environment to the control of a human will.

The recognition of the insuperable limits to his knowledge ought indeed to teach the student of society a lesson of humility which should guard him against becoming an accomplice in men’s fatal striving to control society — a striving which makes him not only a tyrant over his fellows, but which may well make him the destroyer of a civilization which no brain has designed but which has grown from the free efforts of millions of individuals.

Yes, it surely ought to.

Jeffrey Tucker is Director of Digital Development at FEE, CLO of the startup Liberty.me, and editor at Laissez Faire Books. Author of five books, he speaks at FEE summer seminars and other events. His latest book is Bit by Bit: How P2P Is Freeing the World. Follow on Twitter and Like on Facebook.

This feature film is narrated by Brian Sussman, San Francisco radio host (KSFO) and best-selling author of

This feature film is narrated by Brian Sussman, San Francisco radio host (KSFO) and best-selling author of

As a result, Athens has really and truly run out of money, and they will default on their debts starting tomorrow — and the European Central Bank has said

As a result, Athens has really and truly run out of money, and they will default on their debts starting tomorrow — and the European Central Bank has said