Restoring Civilization: We Can’t MAGA Unless We MAMA

They can sense it. They can feel it. Something is seriously wrong in our civilization, and many people know it. This is why despite the relatively good economic times, most Americans polled say our country is on the “wrong track.” Yet many are like a gravely ill man who knows he’s not well but can’t precisely identify his ailment. Most often, Americans have only a vague sense of cultural malaise, or they “self-diagnose” wrongly.

Years ago I had a brief “state of the nation” discussion with a very fine, older country gentleman. While no philosopher, he did offer the following diagnosis. Struggling for words and gesticulating a bit, he said, “There’s…there’s no morality.”

Most believe morality is important both personally and nationally. We generally agree that an immoral man treads a dangerous path; of course, it’s likewise for two immoral men, five, 53 or 1,053 — or a whole nation-full.

Echoing many Founders, George Washington noted that “morality is a necessary spring of popular government.” The famous apocryphal saying goes, “America is great because America is good, and if she ever ceases to be good, she will cease to be great.” For sure, we can’t MAGA unless we MAMA — Make America Moral Again.

Yet if immorality is the diagnosis and restoring morality the cure, we must know what this thing called “morality” is. Ah, that’s where agreement can end.

Talk to most people today — especially the people who study people, sociologists and anthropologists — and they’ll “identify morality with social code,” as Sociology Guide puts it. They’ll essentially say what sociologists Durkheim and Sumner do, “that things are good or bad if they are so considered by society or public opinion,” the site continues. “Durkheim stated that we do not disapprove of an action because it is a crime but it is a crime because we disapprove of it.” Yet true or not, would the majority really view an action as a crime, in the all-important moral sense, if they came to believe it was true?

Consider a man I knew who once proclaimed, “Murder isn’t wrong; it’s just that society says it is.” Clearly, “public opinion” isn’t swaying him much.

Yet how do you argue with him? Barring reference to something outside of man (i.e., God) dictating murder’s “immorality,” you’re left with a striking reality:

Society is all there is to say anything.

Then “Man is the measure of all things,” as Greek philosopher Protagoras put it.

Yet acceptance of the “society says” thesis presents a problem: Now you must convince others to equate “public opinion” with credible, binding “morality.” This is mostly fruitless because, frankly, it’s stupid.

Man’s opinion is just that — opinion. If the term “morality” is essentially synonymous, it’s a risible redundancy. If we’re acting as slick marketers, trying to elevate “opinion” via assignment of an impressive-sounding title, it’s false advertising. So if that is all we’re really talking about — “opinion” or “societal considerations” — let’s drop the pretense and just say what we mean:

We sentient organic robots (soulless entities comprising chemicals and water) have preferences for how others should behave (subject to change with or without notice). No, we can’t call these tastes “morality” — but, hey, we can punish the heck out of you for defying our collective will (see North Korea et al.).

To cement the point, consider my patent explanation. Who or what determines what this thing we call morality is?

Only two possibilities exist: Either man or something outside of him does. If the latter, something vastly superior and inerrant (i.e., God), then we really can say morality exists, apart from man. It’s real. Yet what are the man-as-measure implications?

Well, imagine the vast majority of the world loved chocolate but hated vanilla. Would this make vanilla “wrong” or “evil”? It’s just a matter of preference, of whatever flavor works for you.

Okay, but is it any more logical saying murder is “bad” or “wrong” if we only do so because the vast majority of the world prefers we not kill others in a manner the vast majority considers “unjust”? If it’s all just consensus “opinion,” it then occupies the same category as flavors: preference.

This is the matter’s stark reality, boiled down. It’s why serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer’s darkness-enabling attitude was, as his father related in a 1996 interview (video below; relevant portion at 40:26), “If it [life] all happens naturalistically, what’s the need for a God? Can’t I set my own rules?” It’s why occultist Aleister Crowley, branded “the wickedest man in the world,” succinctly stated, “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law” (Preference Über Alles 101).

[Please insert: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jgw0x0TxRO8]

This perspective engenders what’s often called “moral relativism,” the notion that “Truth” (absolute by definition) is illusion and what’s called “morality” changes with the time and people. But saying all is preference is actually moral nihilism, the belief that “morality” (properly understood) doesn’t actually exist — because, again, “opinion” isn’t morality.

Of course, few think matters through as thoroughly as a Dahmer or Crowley. (In fact, a possible reason sociopaths may possess above-average intelligence is that they’re smart enough to grasp the “morality” question’s two possibilities — either morality exists as something divinely-authored, something transcendent, or there is no morality — but draw the wrong conclusion.) Yet moral relativism/nihilism has swept Western civilization. And hell has followed with it.

How relativistic/nihilistic are we? A Barna Group study found that in 2002 already, most Americans did not believe in (absolute) Truth, in morality; in fact, only six percent of teens did. Thus are they most likely to base what once were called “moral decisions” on…wait for it…feelings. Surprise, surprise.

Such prevailing philosophical/moral rot collapses civilization. For anything can be justified. Rape, kill, steal, violate the Constitution as a judge, commit vote fraud? Why not? Who’s to say it’s wrong? Don’t impose values on me, dude.

To analogize it, imagine we fell victim to “dietary relativism/nihilism” and fancied the rules of nutrition nonexistent. With only taste left to govern dietary choices, most would indulge junk food; nutritional disorder would reign and health deteriorate. Moreover, considering one man’s poison another’s pleasure, we might sample those pretty red berries the birds gobble down. Hey, if it tastes good, eat it.

This reflects what’s befalling our “If it feels good, do it” Western civilization. Considering the rules of any system non-existent or irrelevant brings movement toward disorder — and a point where those who can impose their preferences restore order, a tyrannical one.

Having said this, discussing “Truth” and God evokes complaints, as the morally relativistic/nihilistic world view influences even many conservatives, and secularists find faith-oriented talk unsettling.

So let’s focus here on not faith but fact. As to this and the world’s Dahmers, Crowleys and the murder-skeptic man I knew, call them names, but don’t call them illogical. Within their universe of “data”— that “God doesn’t exist” and thus only organic robots can be the measure — they’re right: Murder’s status isn’t “wrong,” just “unpreferred.”

Note that moral principles cannot be proven scientifically any more than God’s existence; you can’t see a moral under a microscope or a principle in a Petri dish. Science only tells us what we can do, not what we should. Finding guidance on “should” necessitates transcending the physical and venturing into the metaphysical. It requires, pure logic informs, taking a leap of faith.

Something else not a matter of faith but fact is man’s psychology: People operate by certain principles. Like it or not, believing as Dahmer did (when young) about God leads to believing as he did about morality. “If man is all there is to make up rules, why can’t I just make up my own?”

As I put it in 2013, “Just as people wouldn’t abide by the ‘laws’ of physics if they didn’t believe they existed (the idea of jumping off a building and flying sounds like fun), and there weren’t obvious and immediate consequences for their violation (splat!), they won’t be likely to abide by morality if they believe its laws don’t exist.”

Of course, this rarely leads to serial killing. But it always — at population level — leads to serial immorality. This is an immutable rule of man.

So how should we combat our time’s moral relativism/nihilism? First, realize that from the Greek philosophers to the early/medieval Christians to the Founding Fathers, Western civilization was not forged by relativists/nihilists. It won’t be maintained by them, either. “If it feels good, do it” yields a healthy society even less than “If it tastes good, eat it” does a healthy body.

Thus, one needn’t have faith to understand that belief in Truth is utilitarian. As George Washington warned, “[R]eason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.”

Second, know that moral relativism/nihilism’s appeal is that it’s the ultimate get-out-of-sin free card. After all, my sins can’t be sins if there are no such things as sins, only “lifestyle choices.” Yet also know that we can have this seemingly eternal but illusory absolution — or we can have civilization. We can’t have both.

So act as if Truth exists; seek it, speak it, love it, for it will set you free. Realize also that relativism is juvenile pseudo-philosophy. For if everything were relative, what you believed would be relative, too, and thus meaningless. So let’s talk about what’s meaningful.

The alternative? Well, it was expressed nicely by an old New Yorker cartoon. It featured the Devil addressing a large group of arrivals in Hell and saying, reassuringly, “You’ll find there’s no right or wrong here. Just what works for you.”

It’s an alluring idea — and a powerful one. It creates Hell on Earth, too.

Contact Selwyn Duke, follow him on Gab (preferably) or Twitter or log on to SelwynDuke.com.

RELATED VIDEOS:

America’s Anti God Rebellion

The Make America Great Formula.

EDITORS NOTE: This article is the second in a series on exposing modern (liberal) lies, explaining the disordered leftist mind and restoring civilization. The first is here. The “American’t” essay, which illustrates our problems, is here. The edited featured photo by Jonny Swales on Unsplash.

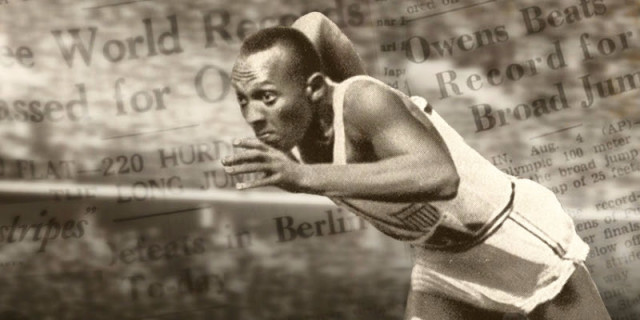

We dined at the Bonefish Grill on Abercorn Street, then went to see the fantastic film Race about Olympian

We dined at the Bonefish Grill on Abercorn Street, then went to see the fantastic film Race about Olympian

Thus, our number one recommendation is to read and/or assign

Thus, our number one recommendation is to read and/or assign