Fauci Claims He Had ‘Nothing to Do’ With School Closures. His Own Statements Suggest Otherwise

Dr. Anthony Fauci’s recent dodge on school closures is at odds with many of his own statements.

The economist John Kenneth Galbraith once quipped, “Nothing is so admirable in politics as a short memory.”

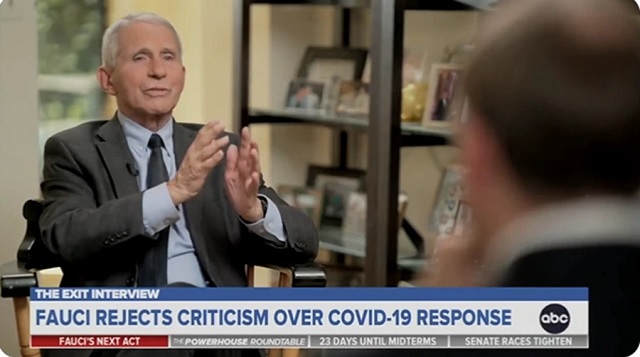

The line comes to mind after watching Dr. Anthony Fauci’s interview with ABC’s Jonathan Karl over the weekend. In the interview, Fauci, the head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), was asked whether it was a “mistake” for schools to remain shut down for so long during the pandemic.

“I don’t want to use the word ‘mistake,’ Jon, because if I do, it gets taken out of the context that you’re asking me the question on,” Fauci explained on Sunday. “We should realize, and have realized, that there will be deleterious collateral consequences when you do something like that.”

Fauci is correct that there were serious “deleterious” consequences of school closures. For example, it was recently reported that the class of 2022 saw average ACT scores plummet to the lowest level in more than thirty years, and there’s no reason to believe that younger students didn’t experience similar results. Lost learning is hardly the only “deleterious” consequence, however; the decline of mental health among youths during lockdowns has also been well chronicled.

Some may see Fauci’s response as reasonable, because he’s now acknowledging the collateral damage of these policies. The problem is that Fauci is not actually conceding anything. Nobody—and I mean nobody—ever believed you could shut down schools (and society more broadly) for any meaningful amount of time and not experience some “deleterious” consequences.

But it gets worse. Fauci goes on to claim he had nothing to do with the damaging policy.

“I ask anybody to go back over the number of times that I have said we’ve got to do everything we can to keep the schools open, no one plays that clip,” Fauci told Karl. “They always come back and say, ‘Fauci was responsible for closing schools.’ I had nothing to do [with it].”

ABC News: "Was it a mistake, in so many states and so many localities, to see schools closed as long as they were?"

Dr. Fauci: “I don't want to use the word mistake, Jon…They always come back and say, ‘Fauci was responsible for closing schools.’ I had nothing to do [with it].” pic.twitter.com/dyERywd2uW

— Jon Miltimore (@miltimore79) October 18, 2022

6 Times Fauci Argued for School Closures

Fauci may not have sat on a school board or wielded police power during the pandemic, but his claim that he bears no responsibility for school closing takes chutzpah. It’s undeniable that many schools, cities, and state governments shut down schools precisely because of what the White House’s top medical advisor was saying, and what Fauci was saying was clear.

The journalist Jordan Schachtel has a timeline of Fauci’s statements on school reopenings, and it’s worth examining.

3/12/20:

Fauci calls for a nationwide shutdown of schools.

“The one thing I do advise and I said this in multiple hearings and multiple briefings, that right now we have to start implementing both containment and mitigation. And what was done when you close the schools is mitigation.”

NIH's Dr Anthony Fauci supports school closings. Says steps need to be taken for containment and mitigation of Coronavirus. Says we need to distance ourselves from each other. Denies it's overreacting. And says restricting travel from Europe is "the right public health call." pic.twitter.com/iZJi4zlabA

— Mark Knoller (@markknoller) March 12, 2020

4/12/20:

The New York Times, America’s paper of record, reports that Fauci ‘gave his blessing’ to Mayor Bill DeBlasio to shut down the New York City school system.

De Blasio this morning: "Lord knows, having to tell you that we cannot bring our schools back for the remainder of this school year is painful. But I can also tell you it's the right thing to do."

Full story here: https://t.co/iPGwBKJpW5— Eliza Shapiro (@elizashapiro) April 11, 2020

4/13/20:

Fauci slams Ron DeSantis after the Florida governor announced he wanted to get schools open “as soon as possible.”

“If you have a situation where you don’t have a real good control over an outbreak and you allow children together, they will likely get infected,” Fauci stated.

President Donald Trump and top White House health officials said a proposal to reopen Florida schools next month could help spread the coronavirushttps://t.co/GEYZnE7noG

— POLITICO (@politico) April 11, 2020

5/12/20:

Fauci has a testy exchange with Sen. Rand Paul, who argued schools should remain open.

Fauci dismissed the idea that schools should be opened back up fully because “we don’t know everything about the virus.”

CNBC reports: Fauci then turned Paul’s own phrasing on him. “You used the word we should be ‘humble’ about what we don’t know. I think that falls under the fact that we don’t know everything about this virus, and we really had better be very careful, particularly when it comes to children,” Fauci said. “Because the more and more we learn, we’re seeing things about what this virus can do that we didn’t see from the studies in China or in Europe. For example, right now children presenting with Covid-19 who actually have a very strange inflammatory syndrome, very similar to Kawasaki syndrome,” Fauci said.

In August and September, Fauci was singing the same tune. Schools could open for instruction—after the virus was under control.

8/4/20 Fauci on schools:

"There may be some areas where the level of virus is so high that it would not be prudent to bring children back to school."

In clip, he endorses Zoom education & school closures in areas w/ COVID transmission. Fauci has never been for full reopening. pic.twitter.com/eORstr2Lf8

— Jordan Schachtel @ dossier.substack.com (@JordanSchachtel) November 30, 2020

‘I Didn’t Recommend Locking Anything Down’

Fauci’s about-face did not go unnoticed. Other health researchers questioned his attempt to distance himself from school closures.

“Why is he saying he did not encourage, suggest and recommend lockdown and school closure?” asked Vinay Prasad, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco. “Certainly he didn’t make the call by himself, but he used the weight of his reputation in science to advocate for these policies… .”

Why is he saying he did not encourage, suggest and recommend lockdown and school closure? Certainly he didn't make the call by himself, but he used the weight of his reputation in science to advocate for these policies, & quelch dissent

You have own your mistakes, not deny them https://t.co/c2xNWDnrCe

— Vinay Prasad MD MPH (@VPrasadMDMPH) October 17, 2022

This is not the first time Fauci has attempted to deflect blame for school closures and lockdowns. In a July interview with Newsweek deputy editor Batya Ungar-Sargon, Fauci was asked if he would recommend closing schools again, considering the amount of collateral damage the policies caused.

“First of all, I didn’t recommend locking anything down,” Fauci responded, adding that that was the purview of the CDC.

Fauci was correct that it was the proper purview of the CDC to make specific policy recommendations, not the head of NIAID, whose job was to see that his agency provided sound scientific research to the CDC. Yet this did not seem to stop the doctor from becoming essentially the official spokesman of the federal government’s public health response, conducting literally hundreds of interviews during the pandemic and posing for numerous magazine shoots. (Many public health experts I’ve spoken with say this is precisely why science became so politicized during the pandemic.)

Ummm. Does he think we’ve all got collective amnesia? https://t.co/vGDsRdCBA0

— Rita Panahi (@RitaPanahi) July 26, 2022

Now that these policies are rightly being criticized for their “deleterious” consequences, Fauci—who grew quite wealthy as a result of all the media attention he received—is claiming he had “nothing to do” with the policies.

Fauci’s claims are almost too hard to believe, but they call to mind a piece of wisdom from economist Thomas Sowell.

“It is hard to imagine a more stupid or more dangerous way of making decisions than by putting those decisions in the hands of people who pay no price for being wrong,” Sowell once observed.

The pandemic shows just how right Sowell was.

AUTHOR

Jon Miltimore

Jonathan Miltimore is the Managing Editor of FEE.org. His writing/reporting has been the subject of articles in TIME magazine, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, Forbes, Fox News, and the Star Tribune. Bylines: Newsweek, The Washington Times, MSN.com, The Washington Examiner, The Daily Caller, The Federalist, the Epoch Times.

EDITORS NOTE: This FEE column is republished with permission. ©All rights reserved.