California’s Statewide $15 Minimum Wage Will Horribly Backfire for Poorer Cities by Mark J. Perry

I wrote earlier this month about one of the potentially fatal flaws of California’s recently enacted $15 an hour statewide minimum wage: a one-size-fits-all uniform $15 minimum wage for the entire state of California is really a “one-size-fits-none” minimum wage, given the huge variations in the cost of living around the country’s most populous state.

While a high-wage, high cost-of-living city like San Francisco might be able to absorb a $15 minimum wage without experiencing significant negative employment effects, that same $15 wage could inflict serious economic damages and result in job losses for many of the state’s 500 cities that are in low-wage, low cost-of-living areas.

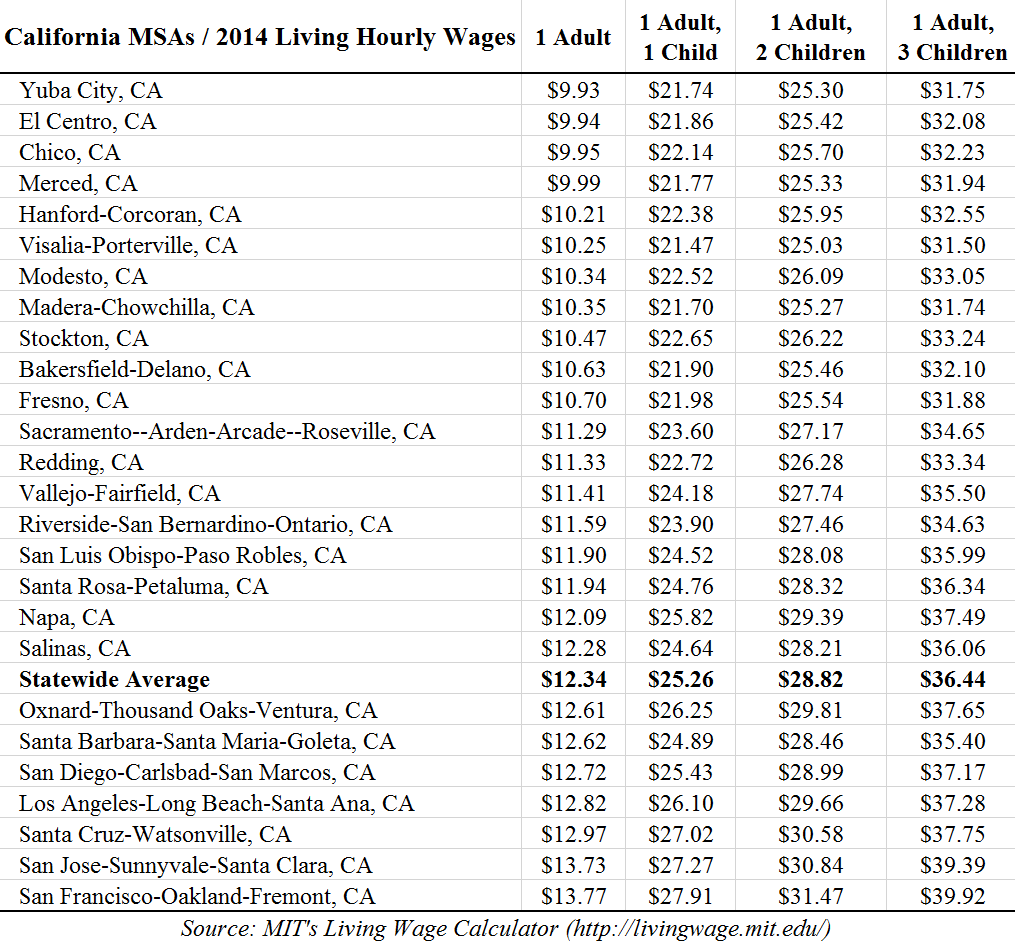

To help understand how the “one-size-fits-all” approach of a $15 an hour state minimum wage will have a disproportionately adverse impact on low-cost communities in California, the table below displays the “living hourly wages” for California’s 26 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), based on data from MIT’s Living Wage Calculator for the year 2014 (most recent year available).

According to the MIT website, the cost-of-living adjusted living wages are the “hourly rates that individuals must earn [in a given MSA] to support their family [and cover basic family expenses], if they are the sole provider and are working full-time (2,080 hours per year).” Living wages for adult workers with 1 to 3 children are also displayed in the table.

The living wage data shown above reveal huge differences in the cost-of-living between low-cost California MSAs like Yuba City, El Centro, Chico, and Merced (living wages are below $10 an hour) and high-cost cities like San Francisco and San Jose, where the cost-of-living adjusted living wage is 38% higher.

If $15 an hour is an appropriate minimum wage for San Francisco, it should be less than $11 an hour in MSAs like Yuba City and El Centro, where the cost-of-living is significantly lower. It’s also important to note that all four of those low-cost MSAs had jobless rates above the state average in February, and three of them (all except Chico) had double-digit unemployment rates in February, with El Centro having the distinction of once again being the MSA with the highest jobless rate in the entire country at 18.6%.

Therefore, many MSAs in California (like Yuba City, El Centro, Chico and Merced) not only have costs-of-living way below the state average, but they also have jobless rates that are way above the state average, and it’s those MSAs that will be adversely impacted by the imposition of a uniform state minimum wage of $15 an hour.

Bottom Line: As I concluded before, even supporters of a $15 an hour minimum wage in California would have to concede that a one-size-fits-all, uniform $15 an hour state minimum wage, without any adjustments for the significant differences in the cost-of-living across the Golden State, will disproportionately affect unskilled and limited-experience workers in low-cost MSAs like Yuba City and El Centro, and also in hundreds of other low-cost, low-wage cities (that are not part of an MSA) throughout the state.

In other words, a one-size-fits-all minimum wage for all 500 cities in California is really a “one-size-fits-none” minimum wage, and will inflict very serious and long-lasting economic damage in most parts of the state outside of the large metro areas on the coast (LA, San Francisco, and San Diego).

The clumsy, top-down, ham-handed approach of government imposed wage controls like a $15 an hour statewide minimum wage in California, without allowing for any adjustments to accommodate the significant differences in cost-of-living and labor market conditions, is one of the main reasons the Golden State’s risky experiment with a $15 wage will likely backfire and be “not-so-golden” in practice.

In contrast, one of the significant advantages of market-determined wages is that they can naturally and automatically adjust to the market conditions of local areas. For example, we might expect that the starting wages for national chains like McDonald’s (1,165 stores in California) and Starbucks (2,000 locations) would vary around the state of California based on local labor market conditions and the local cost-of-living, and would be higher in San Francisco than in cities like El Centro.

But a government mandated price control like the $15 an hour uniform minimum wage in California that outlaws adjustments to fit the customized needs of the 500 individual city-level labor markets in the state is a public policy destined to fail — especially in the state’s low-wage, low cost-of-living cities with high jobless rates that are the most vulnerable to the “one-size-fits-none” awkwardness and clumsiness that is the $15 statewide minimum wage in California.

Related: See my article with AEI colleague Andrew Biggs titled “A National Minimum Wage Is a Bad Fit for Low-Cost Communities.”

Bonus Question: I included the living wages above that MIT calculated would be necessary to support an adult-headed household with either one, two or three children so that I could feature the question posed below by Georgetown University professor Jason Brennan at the Bleeding Heart Libertarians blog in his post titled “Some Questions for Living Wage Advocates” (h/t Don Boudreaux):

If you believe employers owe employees a living wage, do you think that an employer has a moral duty to pay an employee more just because [he or] she has more children?

Reprinted with the permission of the American Enterprise Institute.

Mark J. Perry is a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and a professor of economics and finance at the University of Michigan’s Flint campus.