Leftists Are Using Race to Push an Anti-American Agenda

Our country is under attack from radical leftists. Mobs rampage through our streets, monuments are being destroyed, and the very law and order that ensures our communities’ peace and security is being undermined.

In far too many instances, those bent on destruction have hijacked protests, creating violence and division, and ultimately attacking the very foundation of our nation. For them, it’s not about resolving race issues; it’s about using racial discontent to forward their anarchist agenda.

One such group is Antifa. While it is widely recognized as a far-left fringe group, another organization—just as radical—has managed to drape itself in more mainstream clothes, gaining significant support with the public, politicians, and the business community.

While Americans of every color agree with the sentiment that black lives matter, Black Lives Matter the organization actually advocates an agenda that is completely out of step with American values.

In these trying times, we must turn to the greatest document in the history of the world to promise freedom and opportunity to its citizens for guidance. Find out more now >>

One look at the Black Lives Matter organization’s website shows that the idea of protecting black lives and seeking justice is merely a vehicle to advance a different, radical set of ideas. The organization is more dedicated to gaining political power and remaking America according to Marxist ideology. Two of the group’s three co-founders are even “trained Marxists,” according to one of them.

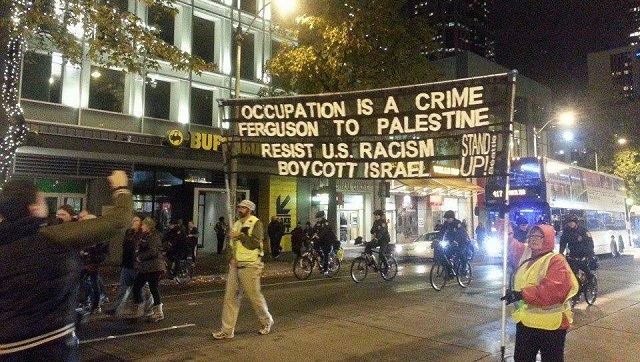

And it shows. The group’s platform includes planks unrelated to improving black lives, like trying to get the U.S. to divest from Israel, which it calls an “apartheid state” while accusing Jews of committing genocide against Palestinians.

The organization also has called for dismantling the family, saying, “We disrupt the Western-prescribed nuclear family structure.”

The breakdown of the black family and the rise of single-parent households is one of the root causes of poverty, crime, drug abuse, and poor educational achievement in many black communities. Why would anyone who’s supposedly working for black progress want to tear down the very thing that helps to achieve it?

Just as disturbing is the fact that some of America’s biggest corporations are giving hundreds of thousands and even millions of dollars to this organization and others whose misleading names conceal a more expansive and dangerous agenda.

Groups such as Antifa and the Black Lives Matter organization want to impose an ideology on America that would only bring greater poverty, a loss of freedom, destruction to churches and civil society, and violent law enforcement tactics to enforce compliance—exactly what we’ve seen in places such as Venezuela, Cuba, and North Korea.

In fact, we’ve already seen a vision of what their America would look like.

We’ve seen videos of leftist protesters physically and verbally attacking police officers.

We’ve seen an entire neighborhood turned into a violent “autonomous zone” with spineless politicians telling the police to stand down and let anarchists rule over innocent residents.

We’ve seen violent mobs defacing and toppling statues of historical figures such as soldiers and abolitionists. Some are even calling for the removal of images of Jesus in which he is perceived as “too white.”

We must stop the violence and destruction and bring those committing criminal acts to justice while protecting the rights of good people to protest peacefully.

We must support our police officers who risk their lives every day to protect us no matter our color, religion, sex, or nationality—while also making needed reforms to weed out bad cops and end unacceptable policing procedures.

Calls to defund the police are calls for chaos, and calls to disarm them are lunacy. We’ve seen what happens in Seattle, Minneapolis, and other cities when criminals are allowed free rein.

Finally, we must combat the Marxist agenda. This agenda has wrought destruction on nations for generations. It expands government control and takes every opportunity to limit freedom—and it must not take root in the United States.

The most desperate communities in America have been run by the left for a generation or more. We’ve seen what that leadership has brought: generational poverty, fatherless families, worse educational outcomes, more disparity, and higher crime rates. Lurching even further left would be even more disastrous.

Instead, we must implement policies to ensure America’s promise of liberty and opportunity is a promise for all Americans. Conservatives always have had the policies that can help solve many of the difficult issues that Americans face.

We know how to create jobs, end poverty, provide better access to health care, improve education, and strengthen families better than anyone. And our fundamental belief in the inherent dignity of every human being can help bring about the healing our nation so desperately needs.

America is a land of promise, and conservative policies can make those promises ring true for all Americans. It is time for conservatives to take a message of hope to every American to end the racial strife and build an America where freedom, opportunity, prosperity, and civil society flourish for all.

Originally published by Fox News

COMMENTARY BY

Kay C. James

Kay C. James is president of The Heritage Foundation. James formerly served as director of the U.S. Office of Personnel Management and as Virginia’s secretary of health and human resources. She is also the founder and president of The Gloucester Institute. Twitter: @KayColesJames.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Watch: Black Conservatives Laugh as They Stumble Upon BLM Protest Missing 1 Important Thing

Gingrich Calls on Conservatives to Focus on ‘Black Success,’ Not ‘White Guilt’

Don’t Allow a Vocal Fringe Minority to Cut Our Much-Needed Defense Investments

4 Points to Understand the COVID-19 Surge in Texas

A Note for our Readers:

This is a critical year in the history of our country. With the country polarized and divided on a number of issues and with roughly half of the country clamoring for increased government control—over health care, socialism, increased regulations, and open borders—we must turn to America’s founding for the answers on how best to proceed into the future.

The Heritage Foundation has compiled input from more than 100 constitutional scholars and legal experts into the country’s most thorough and compelling review of the freedoms promised to us within the United States Constitution into a free digital guide called Heritage’s Guide to the Constitution.

They’re making this guide available to all readers of The Daily Signal for free today!

GET ACCESS NOW! >>

EDITORS NOTE: This Daily Signal column is republished with permission. ©All rights reserved.

We have an extensive archive on Sweden,

We have an extensive archive on Sweden,