The climate-change debate has many people wondering whether we should really turn over public policy — which deals with fundamental matters of human freedom — to a state-appointed scientific establishment. Must moral imperatives give way to the judgment of technical experts in the natural sciences? Should we trust their authority? Their power?

There is a real history here to consult. The integration of government policy and scientific establishments has reinforced bad science and yielded ghastly policies.

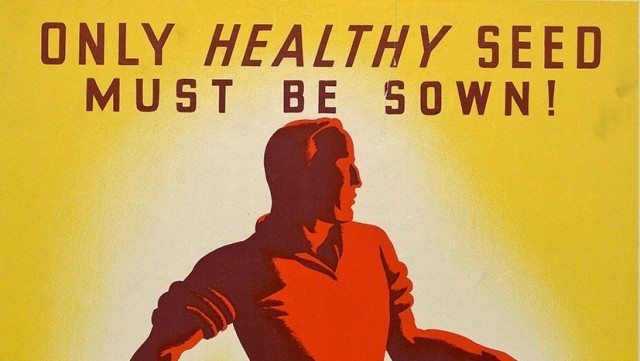

An entire generation of academics, politicians, and philanthropists used bad science to plot the extermination of undesirables.

There’s no better case study than the use of eugenics: the science, so called, of breeding a better race of human beings. It was popular in the Progressive Era and following, and it heavily informed US government policy. Back then, the scientific consensus was all in for public policy founded on high claims of perfect knowledge based on expert research. There was a cultural atmosphere of panic (“race suicide!”) and a clamor for the experts to put together a plan to deal with it. That plan included segregation, sterilization, and labor-market exclusion of the “unfit.”

Ironically, climatology had something to do with it. Harvard professor Robert DeCourcy Ward (1867–1931) is credited with holding the first chair of climatology in the United States. He was a consummate member of the academic establishment. He was editor of the American Meteorological Journal, president of the Association of American Geographers, and a member of both the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Royal Meteorological Society of London.

He also had an avocation. He was a founder of the American Restriction League. It was one of the first organizations to advocate reversing the traditional American policy of free immigration and replacing it with a “scientific” approach rooted in Darwinian evolutionary theory and the policy of eugenics. Centered in Boston, the league eventually expanded to New York, Chicago, and San Francisco. Its science inspired a dramatic change in US policy over labor law, marriage policy, city planning, and, its greatest achievements, the 1921 Emergency Quota Act and the 1924 Immigration Act. These were the first-ever legislated limits on the number of immigrants who could come to the United States.

Nothing Left to Chance

“Darwin and his followers laid the foundation of the science of eugenics,” Ward alleged in his manifesto published in the North American Review in July 1910. “They have shown us the methods and possibilities of the product of new species of plants and animals…. In fact, artificial selection has been applied to almost every living thing with which man has close relations except man himself.”

“Why,” Ward demanded, “should the breeding of man, the most important animal of all, alone be left to chance?”

By “chance,” of course, he meant choice.

“Chance” is how the scientific establishment of the Progressive Era regarded the free society. Freedom was considered to be unplanned, anarchic, chaotic, and potentially deadly for the race. To the Progressives, freedom needed to be replaced by a planned society administered by experts in their fields. It would be another 100 years before climatologists themselves became part of the policy-planning apparatus of the state, so Professor Ward busied himself in racial science and the advocacy of immigration restrictions.

Ward explained that the United States had a “remarkably favorable opportunity for practising eugenic principles.” And there was a desperate need to do so, because “already we have no hundreds of thousands, but millions of Italians and Slavs and Jews whose blood is going into the new American race.” This trend could cause Anglo-Saxon America to “disappear.” Without eugenic policy, the “new American race” will not be a “better, stronger, more intelligent race” but rather a “weak and possibly degenerate mongrel.”

Citing a report from the New York Immigration Commission, Ward was particularly worried about mixing American Anglo-Saxon blood with “long-headed Sicilians and those of the round-headed east European Hebrews.”

Keep Them Out

“We certainly ought to begin at once to segregate, far more than we now do, all our native and foreign-born population which is unfit for parenthood,” Ward wrote. “They must be prevented from breeding.”

But even more effective, Ward wrote, would be strict quotas on immigration. While “our surgeons are doing a wonderful work,” he wrote, they can’t keep up in filtering out people with physical and mental disabilities pouring into the country and diluting the racial stock of Americans, turning us into “degenerate mongrels.”

Such were the policies dictated by eugenic science, which, far from being seen as quackery from the fringe, was in the mainstream of academic opinion. President Woodrow Wilson, America’s first professorial president, embraced eugenic policy. So did Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., who, in upholding Virginia’s sterilization law, wrote, “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

Looking through the literature of the era, I am struck by the near absence of dissenting voices on the topic. Popular books advocating eugenics and white supremacy, such as The Passing of the Great Race by Madison Grant, became immediate bestsellers. The opinions in these books — which are not for the faint of heart — were expressed long before the Nazis discredited such policies. They reflect the thinking of an entire generation, and are much more frank than one would expect to read now.

It’s crucial to understand that all these opinions were not just about pushing racism as an aesthetic or personal preference. Eugenics was about politics: using the state to plan the population. It should not be surprising, then, that the entire anti-immigration movement was steeped in eugenics ideology. Indeed, the more I look into this history, the less I am able to separate the anti-immigrant movement of the Progressive Era from white supremacy in its rawest form.

Shortly after Ward’s article appeared, the climatologist called on his friends to influence legislation. Restriction League president Prescott Hall and Charles Davenport of the Eugenics Record Office began the effort to pass a new law with specific eugenic intent. It sought to limit the immigration of southern Italians and Jews in particular. And immigration from Eastern Europe, Italy, and Asia did indeed plummet.

The Politics of Eugenics

Immigration wasn’t the only policy affected by eugenic ideology. Edwin Black’s War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America’s Campaign to Create a Master Race(2003, 2012) documents how eugenics was central to Progressive Era politics. An entire generation of academics, politicians, and philanthropists used bad science to plot the extermination of undesirables. Laws requiring sterilization claimed 60,000 victims. Given the attitudes of the time, it’s surprising that the carnage in the United States was so low. Europe, however, was not as fortunate.

Freedom was considered to be unplanned, anarchic, chaotic, and potentially deadly for the race.

Eugenics became part of the standard curriculum in biology, with William Castle’s 1916 Genetics and Eugenicscommonly used for over 15 years, with four iterative editions.

Literature and the arts were not immune. John Carey’s The Intellectuals and the Masses: Pride and Prejudice Among the Literary Intelligentsia, 1880–1939 (2005) shows how the eugenics mania affected the entire modernist literary movement of the United Kingdom, with such famed minds as T.S. Eliot and D.H. Lawrence getting wrapped up in it.

Economics Gets In on the Act

Remarkably, even economists fell under the sway of eugenic pseudoscience. Thomas Leonard’s explosively brilliant Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era (2016) documents in excruciating detail how eugenic ideology corrupted the entire economics profession in the first two decades of the 20th century. Across the board, in the books and articles of the profession, you find all the usual concerns about race suicide, the poisoning of the national bloodstream by inferiors, and the desperate need for state planning to breed people the way ranchers breed animals. Here we find the template for the first-ever large-scale implementation of scientific social and economic policy.

Students of the history of economic thought will recognize the names of these advocates: Richard T. Ely, John R. Commons, Irving Fisher, Henry Rogers Seager, Arthur N. Holcombe, Simon Patten, John Bates Clark, Edwin R.A. Seligman, and Frank Taussig. They were the leading members of the professional associations, the editors of journals, and the high-prestige faculty members of the top universities. It was a given among these men that classical political economy had to be rejected. There was a strong element of self-interest at work. As Leonard puts it, “laissez-faire was inimical to economic expertise and thus an impediment to the vocational imperatives of American economics.”

Irving Fisher, whom Joseph Schumpeter described as “the greatest economist the United States has ever produced” (an assessment later repeated by Milton Friedman), urged Americans to “make of eugenics a religion.”

Speaking at the Race Betterment Conference in 1915, Fisher said eugenics was “the foremost plan of human redemption.” The American Economic Association (which is still today the most prestigious trade association of economists) published openly racist tracts such as the chilling Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro by Frederick Hoffman. It was a blueprint for the segregation, exclusion, dehumanization, and eventual extermination of the black race.

Hoffman’s book called American blacks “lazy, thriftless, and unreliable,” and well on their way to a condition of “total depravity and utter worthlessness.” Hoffman contrasted them with the “Aryan race,” which is “possessed of all the essential characteristics that make for success in the struggle for the higher life.”

Even as Jim Crow restrictions were tightening against blacks, and the full weight of state power was being deployed to wreck their economic prospects, the American Economic Association’s tract said that the white race “will not hesitate to make war upon those races who prove themselves useless factors in the progress of mankind.”

Richard T. Ely, a founder of the American Economic Association, advocated segregation of nonwhites (he seemed to have a special loathing of the Chinese) and state measures to prohibit their propagation. He took issue with the very “existence of these feeble persons.” He also supported state-mandated sterilization, segregation, and labor-market exclusion.

That such views were not considered shocking tells us so much about the intellectual climate of the time.

If your main concern is who is bearing whose children, and how many, it makes sense to focus on labor and income. Only the fit should be admitted to the workplace, the eugenicists argued. The unfit should be excluded so as to discourage their immigration and, once here, their propagation. This was the origin of the minimum wage, a policy designed to erect a high wall to the “unemployables.”

Women, Too

Another implication follows from eugenic policy: government must control women.

It must control their comings and goings. It must control their work hours — or whether they work at all. As Leonard documents, here we find the origin of the maximum-hour workweek and many other interventions against the free market. Women had been pouring into the workforce for the last quarter of the 19th century, gaining the economic power to make their own choices. Minimum wages, maximum hours, safety regulations, and so on passed in state after state during the first two decades of the 20th century and were carefully targeted to exclude women from the workforce. The purpose was to control contact, manage breeding, and reserve the use of women’s bodies for the production of the master race.

Leonard explains:

American labor reformers found eugenic dangers nearly everywhere women worked, from urban piers to home kitchens, from the tenement block to the respectable lodging house, and from factory floors to leafy college campuses. The privileged alumna, the middle-class boarder, and the factory girl were all accused of threatening Americans’ racial health.

Paternalists pointed to women’s health. Social purity moralists worried about women’s sexual virtue. Family-wage proponents wanted to protect men from the economic competition of women. Maternalists warned that employment was incompatible with motherhood. Eugenicists feared for the health of the race.

“Motley and contradictory as they were,” Leonard adds, “all these progressive justifications for regulating the employment of women shared two things in common. They were directed at women only. And they were designed to remove at least some women from employment.”

The Lesson We Haven’t Learned

Today we find eugenic aspirations to be appalling. We rightly value the freedom of association. We understand that permitting people free choice over reproductive decisions does not threaten racial suicide but rather points to the strength of a social and economic system. We don’t want scientists using the state to cobble together a master race at the expense of freedom. For the most part, we trust the “invisible hand” to govern demographic trajectories, and we recoil at those who don’t.

But back then, eugenic ideology was conventional scientific wisdom, and hardly ever questioned except by a handful of old-fashioned advocates of laissez-faire. The eugenicists’ books sold in the millions, and their concerns became primary in the public mind. Dissenting scientists — and there were some — were excluded by the profession and dismissed as cranks attached to a bygone era.

Eugenic views had a monstrous influence over government policy, and they ended free association in labor, marriage, and migration. Indeed, the more you look at this history, the more it becomes clear that white supremacy, misogyny, and eugenic pseudoscience were the intellectual foundations of modern statecraft.

Today we find eugenic aspirations to be appalling, but back then, eugenic ideology was conventional scientific wisdom.

Why is there so little public knowledge of this period and the motivations behind its progress? Why has it taken so long for scholars to blow the lid off this history of racism, misogyny, and the state?

The partisans of the state regulation of society have no reason to talk about it, and today’s successors of the Progressive Movement and its eugenic views want to distance themselves from the past as much as possible. The result has been a conspiracy of silence.

There are, however, lessons to be learned. When you hear of some impending crisis that can only be solved by scientists working with public officials to force people into a new pattern that is contrary to their free will, there is reason to raise an eyebrow. Science is a process of discovery, not an end state, and its consensus of the moment should not be enshrined in the law and imposed at gunpoint.

We’ve been there and done that, and the world is rightly repulsed by the results.

Jeffrey A. Tucker

Jeffrey A. Tucker

Jeffrey Tucker is Director of Digital Development at FEE, CLO of the startup Liberty.me, and editor at Laissez Faire Books. Author of five books, he speaks at FEE summer seminars and other events. His latest book is Bit by Bit: How P2P Is Freeing the World. Follow on Twitter and Like on Facebook.