Why Students Give Capitalism an ‘F’ by B.K. Marcus

Not only are young voters more likely to support Democrats than Republicans, they are also more likely to support the most left-wing Democrats. In recent polls of voters under 30, self-declared democratic socialist Bernie Sanders beats the more mainstream Hillary Clinton by almost six-to-one.

Not only are young voters more likely to support Democrats than Republicans, they are also more likely to support the most left-wing Democrats. In recent polls of voters under 30, self-declared democratic socialist Bernie Sanders beats the more mainstream Hillary Clinton by almost six-to-one.

Former professor Mark Pastin, writing in the Weekly Standard, acknowledges some of Clinton’s flaws as a candidate, but concludes that “the most compelling explanation” for young Democrats’ overwhelming preference for Sanders “is that young voters actually like the idea of a socialist revolution.”

I’m embarrassed to confess that when I was a young voter, I probably would have been among the “Sandernistas.”

I don’t think Pastin is right about the revolution, though. Much of Sanders’s success in defanging the word socialism is in pairing it with an emphasis on democracy, as George Bernard Shaw and the Fabians did in an earlier era. Democratic socialists — at least among my comrades — preferred the idea of evolutionary socialism, and we tried hard to distance ourselves from the revolutionary folks.

Whether by evolution or revolution, however, what we all sought was less competition and more cooperation, less commerce and more compassion. Above all, we wanted greater equality.

“When I asked my students what they thought socialism meant,” Pastin writes, “they would generally recite some version of the Marxist chestnut ‘from each according to ability and to each according to need.'” That sounds about right, but add to that the assumption that it’s government’s job to effect the transfer.

My father, gently skeptical of my politics, pointed out a problem confronting American socialists: we tended to imagine ourselves on the receiving end of the redistribution — rob from the rich and give to the rest of us. “However poor we may think we are in the United States,” he told me, “we would have to give up most of what we now have in order to make everyone in the world equal.” This was strange to hear from someone always behind on the rent and facing ever-growing debt.

Pastin makes a related point: “I’ve always thought that socialism appealed to students because they have never not been on the receiving end of government largesse.”

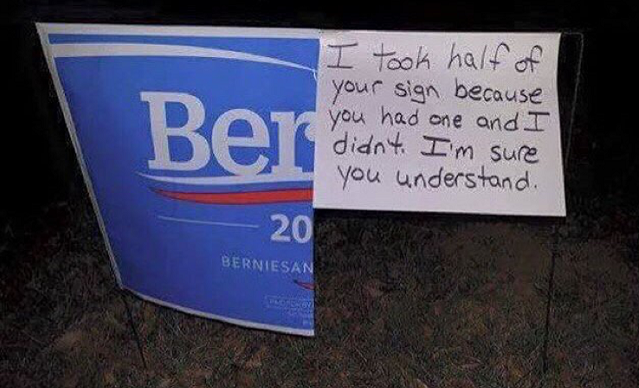

As an informal test of his students’ egalitarian beliefs, Pastin “would offer to run the class along socialist principles, such as the mandate to take from the able and give to the needy.” Specifically, he proposed subtracting points from the A students and transferring them to those who would otherwise earn lower grades.

Even the most ardent socialist students balked at this arrangement. In fact, according to Pastin, the highest-performing students were both more likely to be self-declared socialists and more likely to meet his proposal with outrage: grading, they argued, should be a matter of merit.

Is it pure hypocrisy on the part of these rhetorical radicals, or is there a logical consistency behind this apparent contradiction in their values?

Trying to recall the details of my own callow political folly, I seem to recall three main issues behind my anti-capitalistic mentality:

- “Capitalism” was just the word we all used for whatever we didn’t like about the status quo, especially whatever struck us as promoting inequality. I had friends propose to me that we should consider the C-word a catchall for racism, patriarchy, and crony corporatism. If that’s what capitalism means, how could anyone be for it?

- Even when we left race and sex out of the equation, our understanding of commerce was zero-sum: the 1 percent grew rich by exploiting the 99 percent.

- For whatever reason, none of us imagined we’d ever be business people, except on the smallest possible scale: at farmer’s markets, as street vendors, in small shops. Those things weren’t capitalism. Capitalism was big business: McDonald’s, IBM, the military-industrial complex.

I don’t know how many of today’s young socialists hold these same assumptions, but a question recently posted to Quora.com sounds like it could have been written by one of my fellow lefties in the 1980s: “Should I drop out of college to disobey the capitalist world that values a human with a piece of paper?” (See Praxis strategist Derek Magill’s withering advice to the would-be dropout.)

Even if a different array of confusions drives the radical chic of millennial voters, what is clear is that they see American capitalism as rigged. “Crony capitalism,” from their perspective, is redundant — and “free market” is an oxymoron. They’re not necessarily opposed to meritocracy; they just don’t see what merit has to do with the marketplace.

Grading that would penalize the studious to reward the slackers is obviously unfair, and a sure-fire strategy to kill anyone’s incentive to do the homework. It’s not that the socialist students are applying the principle inconsistently; it’s that they don’t see what merit has to do with commerce. Some of that may be intellectual laziness, some is the result of indoctrination by anti-capitalist faculty, but much of it is also based in the reality of America’s mixed economy.

Not only have young voters spent most of their lives sheltered from the productive side of the commercial world, schooled by men and women who are themselves deliberately insulated from the marketplace, but time spent in the reality of the private sector is hardly an education in what the advocates of economic freedom have in mind when we talk about the free market.

If my own experience is any guide, today’s democratic socialists will have to spend a lot of time unlearning much of what they’ve been taught.

Pastin’s informal experiment is an illuminating first step, and it’s a powerful way to expose the conflict between his students’ understanding of merit and the socialists’ understanding of equality. But there’s also a danger in comparing the economy to the classroom. By offering his grade redistribution as an analogy for socialism, Pastin seems to imply that the merit-based grade system better resembles a free market. But that’s silly.

For one thing, studying hard for your next exam may improve your own GPA, but it probably doesn’t help your classmates. In contrast, an unhampered marketplace makes everyone better off, however unequally.

More significantly, in a free economy, there is no one person in the role of the grade-giving professor. In the absence of coercion, power has a hard time remaining that centralized. Yes, wealth can be seen as a kind of grade, but in the free market, an entrepreneur’s profits and losses are like millions of cumulative grades from the consumers. A+ for improving our lives. F for wasting time and resources.

That kind of spontaneous, decentralized, self-regulating prosperity is every bit as radical as the visions of young socialists, minus the impoverishing effects of coerced redistribution. It’s almost certainly not what they imagine when they say they oppose “capitalism.”

B.K. Marcus is editor of the Freeman.

As shown by the

As shown by the

WASHINGTON, D.C.

WASHINGTON, D.C.

It turned out that Reagan had already thought about this issue. The book

It turned out that Reagan had already thought about this issue. The book