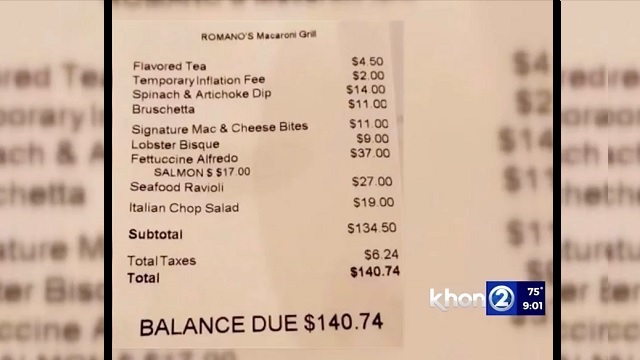

A group of friends had just finished a meal at Romano’s Macaroni Grill in Honolulu when one of them noticed something odd about the check. As a local television news station reported in April, a “Temporary Inflation Fee” of $2.00 was nestled inconspicuously between the $4.50 Flavored Tea and the $14.00 Spinach & Artichoke Dip.

The restaurant chain’s website explained that the charge was added to “partially offset… operational cost increases” due to unusual economic conditions including “global supply chain shortages and ever-growing pressure from inflation.” The statement said, “we believe these burdens will eventually pass,” which is why they resorted to a temporary surcharge instead of simply raising the listed prices. An alternative explanation is that surcharges that show up on the check but not the menu are a sneaky way to try to raise prices without losing customers.

The Wall Street Journal recently cited this incident as part of a general trend:

“Lightspeed, a global developer of point-of-sale software, said fee revenue nearly doubled from April 2021 to April 2022, based on a sample of 6,000 U.S. restaurants that use its platform. The number of restaurants adding service fees increased by 36.4% over the same period.”

The Journal cited industry analysts who basically agreed with Romano’s, explaining that:

“…this wave of surcharges is mostly being driven by restaurants trying to cope with the impact of rising inflation and a tight labor market on their bottom lines.” (…)

“Inflation and the pandemic posed particular challenges for the restaurant industry. The average price of supplies for a restaurant operator increased by 17.5% since last year, according to NPD Group. By comparison, consumer spending at restaurants rose 5% during that time.

The increase in surcharges is a way for businesses to recoup at least some of those costs, said David Portalatin, a food-industry adviser with the group.”

In media coverage of today’s rising prices in general, this has become a prevailing narrative: “businesses are passing their rising costs onto consumers.”

While superficially plausible, this gets the economics of prices the wrong way round.

Upside-Down Economics

The explanation refers to “cost-plus pricing,” which is the business practice of setting prices by starting with your costs and then adding a markup.

Of course, nothing in economics says that a business owner cannot use this method to decide on a price to quote. Surely, some do exactly that. But it is only a heuristic and it is not what fundamentally drives price changes.

Just as “there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch” (TANSTAAFL), there ain’t no such thing as a cost-plus lunch.

To explain price increases as resulting from “passing costs on to the customer” is to implicitly embrace a “cost of production” theory of value and prices, which, in a nutshell, maintains that costs determine prices.

Of course, costs are prices, too. A business’s “costs” are the prices it pays for factors of production (land, labor, and capital goods). So, in a bigger nutshell, this theory posits that “factor prices determine product prices.”

But this is the exact opposite of how an economy actually works. As Murray Rothbard wrote in his economics treatise Power and Market, “Prices, however, are never determined by costs of production, but rather the reverse is true.” In other words, it is anticipated product prices that determine factor prices: prices that determine costs, not the other way around.

This insight was one of the great discoveries that resulted from the “Marginal Revolution” of economics in the 1860s and 70s. This was a literal “revolution” in the sense that it showed the old economic paradigm to be upside-down and then turned it right-side-up.

Before the Marginal Revolution, the “classical economists” largely subscribed to Adam Smith’s cost-of-production theory of value or David Ricardo’s labor theory of value. The latter, like the former, derived the value of products from the value of factors: specifically the factor of labor. (Incidentally, Karl Marx largely based his exploitation and class war theories on Ricardo’s labor theory of value.)

For example, classical economists might have traced the high value of a bottle of fine wine to the high real estate value of the vineyard and/or the amount of labor that went into producing the wine.

But the Marginal Revolutionaries—William Stanley Jevons, Leon Walras, and Carl Menger—upended that paradigm. They and their followers (especially the Austrian school of economics, founded by Menger) explained that the value of a good is based on its “marginal utility,” which is the usefulness for want-satisfaction of an additional unit of a good. And what’s useful about a factor of production is that it can help produce useful products.

For example, the utility of a wine vineyard is that it can yield wine grapes. The same goes for the utility of a vineyard worker’s labor. And the utility of wine grapes is their contribution toward producing enjoyable wine.

So Austrian economists do the opposite of what the classical economists did. Austrians trace the real estate price of the vineyard and the wages of the vineyard worker to the anticipated value of the wine at the end of the production line.

The insights of the Marginal Revolution made it clear that prices determine costs (product prices determine factor prices), not the other way around, and that ultimately consumer preferences determine all prices.

(Note: Alfred Marshall tried to reconcile the classical cost-of-production theory with marginal utility theory in a “neoclassical synthesis” that has influenced mainstream economics to this day. See here for Murray Rothbard’s Austrian critique of that attempt.)

So the “cost passing” explanation of rising prices is a retrogression to a long-overthrown economic paradigm: the economic equivalent of forgetting the heliocentric Copernican Revolution of astronomy and explaining planetary movements using the archaic geocentric model of Ptolemy. Just as the sun does not revolve around the earth, consumer prices do not revolve around producer costs: quite the opposite.

Why Now and Not Before?

Many on the political left blame corporations for “price gouging” in order to fatten their profits. But blaming rising prices on profit-seeking is like blaming a plane crash on gravity.

Gravity is always pulling down on planes. To explain a plane crash, you have to explain what happened to the factors that had previously counteracted that downward pull. Why did gravity yank the plane down to earth when it did and not before?

Similarly, businesses are always seeking profit and are always ready to raise prices if that is what will maximize profits. To explain precipitous price hikes, you have to explain what happened to the factors that had previously put a lid on that upward price pressure. Why did profit-seeking propel prices skyward recently and not in 2019?

This question is also tricky for those (including some on the political right) who blame rising prices on rising costs. If businesses can preserve profits by raising prices now that their costs are higher, why wouldn’t they have increased profits by raising prices before when their costs were lower?

A business’s customers don’t care about that business’s costs. They care about value. Based on the value they expect from a product, there is a limited price range they’d be willing to pay for any given amount of it. That translates into the market demand for the product: the quantity of a good that would be bought at any given price point. The value of, and demand for, a product does not fluctuate with its production costs.

Even businesses don’t (or at least shouldn’t) really care about past costs when it comes to pricing. Past costs are sunk. Whatever was spent to produce it, at any given moment a business has a given inventory. Its best interest is to price that inventory so as to maximize revenue given current demand. Based on that definite demand, raising prices past a certain point will result in less revenue, regardless of past costs. If the most revenue they can hope for is less than their past expenditure, that’s just the way things turned out. They can learn from that error and from those losses by spending less and/or differently in the future. But they cannot change the past or defy the economic reality of the present.

As economist Jonathan Newman told FEE in an interview:

“There is no change in costs that directly affects the revenue-maximizing price. If the prevailing market price is one that maximizes revenue for the firm, then it is impossible for the firm to ‘pass on’ costs to the consumer by increasing prices, because this would result in less revenue.”

Newman reminds us that, “factors of production are valued because they help us make consumer goods, not the other way around. What consumers are willing to pay for consumption goods determines what entrepreneurs are willing to pay for land, labor, and capital goods.” He offers an extreme example to make this point:

“Suppose that tomorrow the government decides to tax the sale of ink for ballpoint pens at $1 billion per mL. Would pen makers be able to carry on as usual and pass this increased cost on to consumers? Would consumers be willing to pay $1,000,000,000.25 for a pen? Of course not. Anticipated consumer demand is a limit on what producers will pay for inputs. More expensive inputs does not mean consumers are ready to pay a higher price for outputs.”

The Real Culprits

So if “cost passing” isn’t what’s driving up prices, what is? Newman points to monetary expansion by central banks, especially the Federal Reserve:

“I suspect that many firms will be able to get away with increased prices because of this. Even if their stated intention is to ‘pass on’ or share costs with their customers, the increased demand from the trillions of dollars that have been injected into the economy over the past couple years is what really makes their price increases both necessary and feasible.”

It is important to note that monetary price inflation is also not “passed on” from suppliers to customers, as “inflation surcharges” might lead you to believe. Again, the reality is the reverse of that. Extra money enables customers to bid up the prices charged by their suppliers, who in turn use the extra money to bid up the prices charged by their suppliers, and so on. That is how new money raises prices across the board (although, unevenly) as it circulates through the economy.

Another contributing factor to rising prices, at least in many specific industries, is today’s supply chain crisis. To an extent, Romano’s and industry analysts are right to blame rising restaurant prices on supply constraints. But they are wrong to characterize it as a matter of “passing on” or “recouping” costs. Rather, it is a matter of greater scarcity translating into a higher marginal utility of certain goods and thus higher prices.

For example, a major factor in today’s high food prices is undoubtedly the war in Ukraine. Both Ukraine and Russia were major exporters of grain. But, owing to Russia’s blockade of Ukraine and the West’s sanctions on Russia, grain exports from both countries have been throttled.

As a result, food processors have less grain to produce foodstuffs like, for example, macaroni. And as a result of that, restaurants have less macaroni to produce macaroni dishes. And when there’s less of something, its price tends to go up. That is probably one of the reasons why the Honolulu diners at Romano’s Macaroni Grill discussed above paid $11.00 for “Signature Mac & Cheese Bites.”

This phenomenon is not “passing on costs.” It is the rippling repercussions of economic destruction and impoverishment. The word “passing” implies that consumers are impoverished while producers are not. But that is not the case. Diminished production and greater scarcity impoverish everyone involved.

It is also confusing to call that “inflation,” although both academia and the media tend to lump all price increases together under that term. For any given increase in prices, part of it may be caused by monetary expansion, and another might be due to supply constraints. Personally, I think it would be clearer to call only the former, and not the latter, “inflation.” Price increases due to an increasing abundance of money should be distinguished from price increases due to a declining abundance of goods and services, although the former very frequently causes the latter (especially by creating economic bubbles and crashes).

Especially since the advent of the Covid crisis in 2020, we have suffered plenty of both. Central banks have been driving up prices with money printing sprees undertaken to finance government spending sprees. Governments have also been driving up prices by sabotaging supply chains through lockdowns, business shutdowns, wars, trade restrictions, and other policies of mass economic destruction.

As prices continue to rise and living standards continue to drop, it is important to understand how it is happening, why it is happening, and who is truly to blame.