Gaining the right to be married is a win for liberty because it removes a barrier to free association. But how easily a movement for more freedom turns to the cause of taking away other freedoms!

Following the Supreme Court decision mandating legal same-sex marriage nationwide, the New York Times tells us that, “gay rights leaders have turned their sights to what they see as the next big battle: obtaining federal, state and local legal protections in employment, housing, commerce and other arenas.”

In other words, the state will erect new barriers to freedom of choice in place of the old ones that just came down!

To make the case against such laws, it ought to be enough to refer to the freedom to associate and the freedom to use your property as you see fit. These are fundamental principles of liberalism. A free society permits anything peaceful, and that includes the right to disassociate. Alas, such arguments seem dead on arrival today.

So let us dig a bit deeper to understand why anti-discrimination laws are not in the best interests of gay men and women, or anyone else. Preserving the ability to discriminate permits the market system to provide crucial information feedback to a community seeking to use its buying power to reward its friends and noncoercively, nonviolently punish those who do not share its values.

Ever more, consumers are making choices based on core values. Does this institution protect the environment, treat its workers fairly, support the right political causes? In order to make those choices — which is to say, in order to discriminate — consumers need information.

In the case of gay rights, consumers need to know who supports inclusion and who supports exclusion. Shutting down that information flow through anti-discrimination law robs people of crucial data to make intelligent buying decisions. Moreover, such laws remove the competitive pressure of businesses to prove (and improve) their commitment to community values, because all businesses are ostensibly bound by them.

A market that permits discrimination, even of the invidious sort, allows money and therefore success and profits to be directed toward those who think broadly, while denying money and profitability to those who do not. In this way, a free market nudges society toward ever more tolerant and inclusive attitudes. Money speaks far more persuasively than laws.

Notice that these proposed laws only pertain to the producer and not the consumer. But discrimination is a two-edged sword. The right can be exercised by those who do not like some groups, and it can be exercised by those groups against those who do not like them.

Both are necessary and serve an important social function. They represent peaceful ways of providing social and economic rewards to those who put aside biases in favor of inclusive decision making.

If I’m Catholic and want to support pro-Catholic businesses, I also need to know what businesses don’t like Catholics. If I’m Muslim and only want my dollars supporting my faith, I need to know who won’t serve Muslims (or who will put my dollars to bad use). If a law that prohibits business from refusing to serve or hire people based on religion, how am I supposed to know which businesses deserve my support?

It’s the same with many gay people. They don’t want to trade with companies that discriminate. To act out those values requires some knowledge of business behavior and, in turn, the freedom to discriminate. There is no gain for anyone by passing a universal law mandating only one way of doing business. Mandates drain the virtue out of good behavior and permit bad motivations to hide under the cover of law.

Here is an example from a recent experience. I was using AirBnB to find a place to stay for a friend. He needed a place for a full week, so $1,000 was at stake. The first potential provider I contacted hesitated and began to ask a series of questions that revolved around my friend’s country of origin, ethnicity, and religion. The rental owner was perfectly in his rights to do this. It is his home, and he faces no obligation to open it to all comers.

On the other hand, I found the questions annoying, even offensive. I decided that I didn’t want to do business with this person. I made a few more clicks, cancelled that query, and found another place within a few minutes. The new renter was overjoyed to take in my friend.

I was delighted for two reasons. First, my friend was going to stay at a home that truly wanted him there, and that’s important. Force is never a good basis for commercial relationships. Second, I was able to deny $1K to a man who was, at best, a risk averse and narrow thinker or, at worst, an outright bigot.

Declining to do business with him was my little protest, and it felt good. I wouldn’t want my friend staying with someone who didn’t really want him there, and I was happy not to see resources going toward someone whose values I distrusted.

In this transaction, I was able to provide a reward to the inclusive and broad-minded home owner. It really worked out too: the winning rental property turned out to be perfect for my friend.

This was only possible because the right to discriminate is protected in such transactions (for now). I like to think that the man who asked too many questions felt a bit of remorse after the fact (he lost a lot of money), and even perhaps is right now undergoing a reconsideration of his exclusionary attitudes. Through my own buyer decisions I was actually able to make a contribution toward improving cultural values.

What if anti-discrimination laws had pertained? The man would not have been allowed to ask about national origin, religion, and ethnicity. Presuming he kept his room on the open market, he would have been required under law to accept my bid, regardless of his own values.

As a result, my money would have gone to someone who didn’t have a high regard for my friend, my friend would have been denied crucial information about what he was getting into, and I would not be able to reward people for values I hold dear.

This is precisely why gay rights leaders should be for, not against, the right to discriminate. If you are seeking to create a more tolerant society, you need information that only a free society can provide.

You need to know who is ready to serve and hire gay men and women, so they can be rewarded for their liberality. You also need to know who is unwilling to hire and serve so that the loss part of profit-and-loss can be directed against ill-liberality. Potential employees and customers need to know how they are likely to be treated by a business. Potential new producers need to know about business opportunities in under-served niche markets.

If everyone is forced to serve and hire gays, society is denied important knowledge about who does and does not support enlightened thinking on this topic.

Consider the prototypical case of the baker who doesn’t want to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple. He is within his rights. His loss of a potential customer base is his own loss. It is also the right of the couple to refuse to give this baker business. The money he would have otherwise made can be redirected towards a baker who is willing to do this. It is equally true that some people would rather trade with a baker who is against gay marriage, and they are within their rights as well.

Every act of discrimination, provided it is open and legal, provides a business opportunity to someone else.

How does all this work itself out in the long run? Commerce tends toward rewarding inclusion, broadness, and liberality. Tribal loyalties, ethnic and religious bigotries, and irrational prejudices are bad for business. The merchant class has been conventionally distrusted by tribalist leaders — from the ancient to the modern world — precisely because merchantcraft tends to break down barriers between groups.

We can see this in American history following the end of slavery. Blacks and whites were ever more integrated through commercial exchange, especially with the advance of transportation technology and rising incomes. This is why the racists turned increasingly toward the state to forbid it. Zoning laws, minimum wage regulation, mandatory segregation, and occupational licensing were all strategies used to keep the races separate even as the market was working toward integration.

The overwhelming tendency of markets is to bring people together, break down prejudices, and persuade people of the benefits of cooperation regardless of class, race, religion, sex/gender, or other arbitrary distinctions. The same is obviously and especially true of sexual orientation. It is the market that rewards people who put aside their biases and seek gains through trade.

This is why states devoted to racialist and hateful policies always resort to violence in control of the marketplace. Ludwig von Mises, himself Jewish and very much the victim of discrimination his entire life, explained that this was the basis for Nazi economic policy. The market was the target of the Nazis because market forces know no race, religion, or nationality.

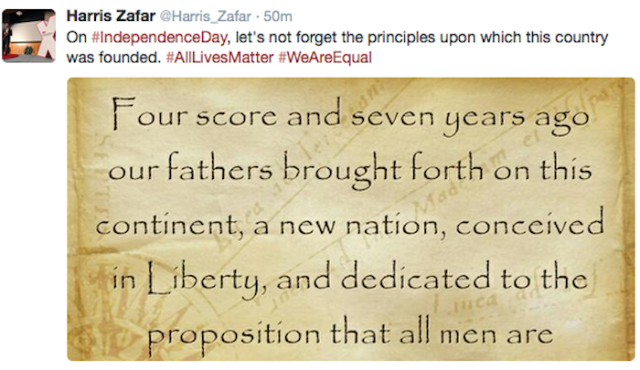

“Many decades of intensive anti-Semitic propaganda,” Mises wrote in 1944, “did not succeed in preventing German ‘Aryans’ from buying in shops owned by Jews, from consulting Jewish doctors and lawyers, and from reading books by Jewish authors.” So the racists turned to the totalitarian state — closing and confiscating Jewish business, turning out Jewish academics, and burning Jewish books — in order to severe the social and economic ties between races in Germany.

The biggest enemy of marginal and discriminated-against populations is and has always been the state. The best hope for promoting universal rights and a culture of tolerance is the market economy. The market is the greatest weapon ever devised against bigotry — but, in order to work properly, the market needs to signaling systems rooted in individuals’ freedom of choice to act on their values.

And, to be sure, the market can also provide an outlet for people who desire to push back for a different set of values, perhaps rooted in traditional religious concerns. Hobby Lobby, Chick-Fil-A, In-and-Out Burger, among many others, openly push their religious mission alongside their business, and their customer base is drawn to them for this reason. This is also a good thing. It is far better for these struggles to take place in the market (where choice rules) rather than through politics (where force does).

Trying to game that market by taking away consumer and producer choice harms everyone. Anti-discrimination laws will provide more choices at the expense of more informed choices. Such laws force bigotry underground, shut down opportunities to provide special rewards for tolerance, and disable the social learning process that leads to an ever more inclusive society.

New laws do not fast-track fairness and justice; they take away opportunities to make the world a better place one step at a time.

Jeffrey A. Tucker

Jeffrey Tucker is Director of Digital Development at FEE, CLO of the startup Liberty.me, and editor at Laissez Faire Books. Author of five books, he speaks at FEE summer seminars and other events. His latest book is Bit by Bit: How P2P Is Freeing the World.

Dinesh D’Souza’s latest #1 New York Times best selling book is “America,” a rebuttal of the progressive shame narrative of American history, now available in paperback for the first time!

Dinesh D’Souza’s latest #1 New York Times best selling book is “America,” a rebuttal of the progressive shame narrative of American history, now available in paperback for the first time!