Who Is Expanding Which War In The Middle East?

Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Palestinians, Yemen | MEMRI Daily Brief No. 567

According to Iranian sources, after the killing of three American soldiers by an Iranian-controlled militia drone on January 28, the Biden Administration feverishly messaged the Iranian regime that “the United States did not want an open war.” Iran supposedly responded that “Tehran rejected Washington’s threats and said targeting its territory is a red line, and crossing the line would be met with an appropriate response. Tehran’s message said that it does not want a war with Washington either, but it will forcefully confront any American adventure.”[1]

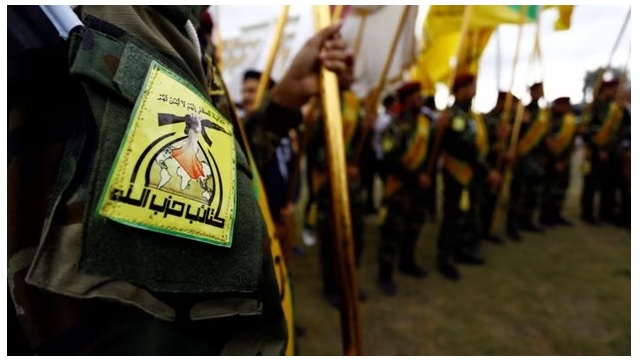

That is likely not the entire story. It is also probable that there was an American warning serious enough to be believed. Something like, “any attack by proxies will be interpreted as a direct Iranian attack and responded to inside Iran.” That is why the Iraqi militia/death squad Kata’ib Hezbollah (KH), widely believed to be the culprit of the attack, announced on January 30 that it was ceasing any attacks on the Americans and claimed that – incredibly – “Iranians had no role in past attacks on American bases in the region.”[2]

The Americans are intending to pull off an interesting trick, simultaneously trying to communicate resolve, power, and appeasement, all at the same time. For an administration that boasted about diplomacy and that painted its predecessor Trump as a dangerous warmonger, the Bidenites have been quite busy in the war business. Aside from simmering tensions with Russia and China, the Americans have used their military to respond to attacks in Syria and Iraq and Yemen in recent months.

But it is true that the United States has sought to prevent a wider war after October 7, 2023, when Hamas invaded Israel. One American goal has been to deter or delay Israel expanding the war into Lebanon against Hezbollah. The Biden Administration has repeatedly and publicly signaled about its concerted efforts to rein Israel in and, indeed, about reining itself in: “We do not want the war to expand.”

The war has expanded nevertheless. The day after the Hamas assault, Lebanese Hezbollah went into action, first at Shebaa Farms and then all along the border with Israel. Israel has responded.

A few rockets were fired into Israel from Syria and the Israelis have responded. The “Islamic Resistance in Iraq,” an umbrella of Iranian-directed Shia militias in Iraq, have claimed several attacks on Israel proper, by drones and missiles. But most of the action in Syria and Iraq has not been directed against Israel but against American military bases in those two countries, with about 160 attacks using Iranian rockets and drones before the deadly success of January 28.[3] The Americans responded occasionally to those attacks inside Syria and Iraq, roughly at the scale of one American response to every 15 attacks on its assets.

On October 19, the Houthis in Yemen entered the war, beginning with several attempted missile strikes on Israel, then strikes on merchants ships possibly connected to Israel, then unconnected merchant shipping, then outright targeting of American warships. Iran openly boasted of this action as part of a broader regional strategy.[4]

And Iran itself has escalated directly over the past month, using a kamikaze drone to strike a tanker in the Indian Ocean and firing missiles from inside Iran to hit a civilian target in Erbil, in Northern Iraq.

Iran has several goals in these attacks. Obviously, it is a basic goal of Iranian policy to drive the United States from the region, beginning with Syria and Iraq. But Iran seeks to pressure the United States with the threat of a wider war in order to motivate the Americans to pressure Israel to stop the war in Gaza so that Iran’s ally Hamas survives the war, more or less, battered but intact.[5]

To accomplish this goal of securing the survival, if not the outright victory, of Hamas both Iran and Qatar pursue complementary strategies. While Qatar seeks to save Hamas through negotiations about hostages, Iran seeks to do so by dangling the specter of a wider conflict before the Americans.[6]

Widening a conflict or escalating it through multiple nodes can be a great equalizer, a type of security jujitsu. After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the U.S. and its allies took a range of punitive actions against Russia. American strategists have boasted of the damage they have been able to inflict on Russia on the battlefield at relatively little cost to the American taxpayer. But everything has a price, especially when it comes to adversaries of substance. We raised the cost to Russia of its actions and Russia has done the same to us – drawing closer to China, empowering Iran and North Korea,[7] projecting power in Africa and even encouraging anti-yanqui rogue states in Latin America. It is no surprise that Russian allies Nicaragua and Venezuela have weaponized migration flows against the United States.[8]

The United States preemptively signaling that it does not want wider wars to adversaries like Iran is making, at least, a rhetorical mistake.[9] Certainly, the United States is in real danger of imperial overreach, of being too involved in too many conflicts, of micromanaging too many things (like trying to do so with Israel in Gaza).[10] But revisionist states like Iran (and Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba) need to understand in a visceral way that the United States has relatively inexpensive ways to inflict pain, to be ruthless against the provocations of adversaries.

Deterrence is not something we tell ourselves but something our adversaries fear about us. Our enemies are starting to believe that we are relatively powerful in principle but constrained in reality, hamstrung mostly by ourselves. In the case of Iran, the Biden Administration has hamstrung itself by three years of pursuing (initially with Russia’s help, by the way) the seductive chimera of a rapprochement with Iran. Where Trump was believed to be unpredictably aggressive, the Biden Administration now – outside Ukraine – is seen as predictably passive. Passive (or complicit) in defending our own borders, passive in supporting our allies, passive in dealing out pain to our adversaries.

This does not require more costly and ponderous American wars, which are something to be avoided. We need to spend less money and be more ruthless, have a lighter footprint with a heavier punch. The Houthis have enemies in Yemen that could be supported as does Hezbollah in Lebanon. The Iranian regime itself has enemies on its borders and inside Iran. The same thing is true with our adversaries in the Western Hemisphere. And, as much as some quarters in the Administration may hate it, unleashing rather than reining in Israel is another way to show Iran that it will pay a heavy price for its actions but one that Washington clearly rejects.[11]

AUTHOR

Amb. Alberto M. Fernandez

Alberto M. Fernandez is Vice President of MEMRI.

SOURCES:

[1] Iranintl.com/en/202401300942, January 30, 2024.

[2] Msn.com/en-us/news/world/iraqs-kataib-hezbollah-says-it-suspends-attacks-on-us-forces/ar-BB1hvRTg, January 30, 2024.

[3] See MEMRI Clip No. 10795 Iraqi Hizbullah Brigades Spokesman Jaafar Al-Husseini: We Have Attacked US Bases In Iraq And Syria, As Well As Vital Targets In Israel; Next Stage Could Include The Gulf Countries; The Resistance Axis Will Spread To East Asia And The Caucasus, January 9, 2024.

[4] See MEMRI Special Dispatch No. 11020, Iranian Regime Mouthpiece ‘Kayhan’: ‘The Most Important Strategy Of The Resistance Front… Must Be To Create Horror In All [Global] Relationships And Commerce With The Zionist Regime’, December 14, 2023.

[5] Middleeasteye.net/opinion/gaza-us-stop-regional-war-reigning-in-israel, January 8, 2024.

[6] Timesofisrael.com/potential-deal-would-reportedly-see-6-week-pause-release-of-all-civilian-hostages, January 31, 2024.

[7] See MEMRI Special Dispatch No. 11103, Russian Outlet On North Korean Foreign Minister’s Visit To Russia: North Korea ‘Is No Longer A Rogue State – It Is A Member Of The Most Powerful Military-Political Bloc On Earth’, January 29, 2024.

[8] Blogs.elconfidencial.com/mundo/tribuna-internacional/2024-01-31/venezuela-petroleo-migracion-extorsion_3820912, January 31, 2024.

[9] Theguardian.com/us-news/video/2024/jan/30/us-says-it-is-not-seeking-war-with-iran-after-troops-killed-in-drone-attack-video, January 29, 2024.

[10] Theamericanconservative.com/how-many-proxy-wars-is-enough, January 30, 2024.

[11] See MEMRI Clip No. 10832, Former Iranian Foreign Minister Ali-Akbar Salehi: The Confrontation Between Iran And Israel Will Continue As Long As Israel Exists; Even If A Palestinian State Is Established, We Will Never Recognize The Plundering Zionist Entity, January 22, 2024.

EDITORS NOTE: This MEMRI column is republished with permission. ©All rights reserved.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!