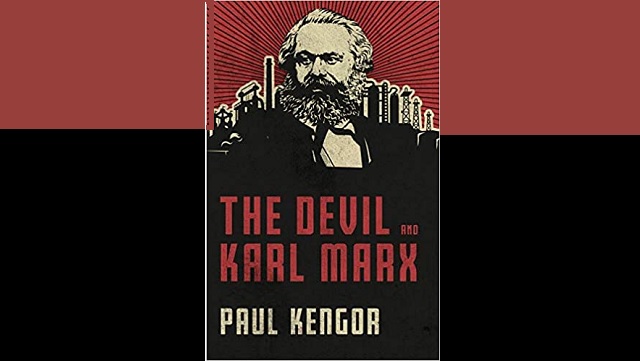

“The Devil and Karl Marx”: A Review

Robert Orlando: In his new book, Paul Kengor plunges a stake into the heart of the devil and Karl Marx. But as we know, such vampires are not so easily killed.

Paul Kengor is a teacher and writer who has always had an eye for the spiritual dimension in history, politics, and economics. (He was the perfect partner for me in our book and documentary film, The Divine Plan: John Paul II, Ronald Reagan, and the Dramatic End of the Cold War.)

Prof. Kengor’s new book, The Devil and Karl Marx: Communism’s Long March of Death, Deception, and Infiltration, is a hammer and sickle dismantling of the diabolical character of Karl Marx (1818-1883). As Michael Knowles writes in the book’s foreword, “Kengor knows, like few others writing today, that terms such as collectivism and individualism only take the debate so far. . . .Ultimately the fight comes down to spiritual warfare: good versus evil.”

Indeed, Kengor’s book is all about the clash of the modern, devilish forces of socialism and communism – the key Marxist systems – against the eternally divine force of faith.

The book opens with a portrait of Marx’s formative early years, an approach similar to Paul Johnson’s in Intellectuals: From Marx and Tolstoy to Sartre and Chomsky (1988). Johnson was accused of being moralistic for judging Marx’s ideas through the lens of his character. Of Marx’s writings, Johnson says their “actual content can be related to four aspects of his character: his taste for violence, his appetite for power, his inability to handle money and, above all, his tendency to exploit those around him.”

Professor Kengor goes even further, depicting Marx as possibly under the Devil’s spell. The young Marx wrote some very dark poems filled with the sort of anti-religious sentiments that would inspire his Communist Manifesto. “It is in part, a tragic portrait of a man,” Kengor writes, “but still more broadly so, an ideology, a chilling retrospective on an unclean spirit that should have never been let out of its pit.”

Here’s an example from Marx’s poem, “The Pale Maiden” (1837):

Thus Heaven I’ve forfeited,

I know it full well.

My soul, once true to God,

Is chosen for Hell.

Kengor (like Johnson) makes the case that Marx, a self-absorbed intellectual, never lived out his own convictions when it came either to money or the redistribution thereof, evidenced by his dismissive attitude towards providing for those under his care. For instance, Marx exhausted the resources and goodwill of his parents, and instead of becoming remorseful or apologetic, he defiantly disowned them once they were no longer of value to him.

When it came to money, everything Marx touched turned to straw. His combustible life was filled with tragedy, debts, and, with the exception of the death of his wife Jenny, an apparent lack of regret in the face of his greatest losses. Family suicides, sexual exploits (including the possible abuse of a family maid) enflamed his life with bloody anger and fueled his revolutionary spirit. In this troubled background are the origins of his communist worldview – a complete rebellion against anything traditional or sacred. Thus the title of Kengor’s book.

Although I agree with the inescapable connection Kengor makes between Marx’s life and his philosophy, I might not place so much emphasis on the man’s early life. Many historical figures were wayward in youth, even some of our saints. Paul the Apostle aided and abetted murder as he tried to violently eradicate the Early Church. We don’t define Augustine by the reckless years prior to his conversion. In fact, these men are saints precisely because they changed.

In Marx’s case, of course, he never changed. He drank the nectar of the devil (my words), and it poisoned him – just as communism poisoned so much of the world.

The middle sections of the book track the rise and fall of the Left’s great messiah and his closest apostle, Friedrich Engels. It continues with a history of Marx’s disciples, from Vladimir Lenin in Russia to Saul Alinsky in the United States.

Kengor also explains how these and other henchmen have assaulted the Catholic faith. Although vigorously opposed by Catholic leadership, Marxism would nonetheless gain a foothold in parts of the Church. Kengor highlights Pope John Paul II’s success in his confrontation with Marxism and communism. Having lived much of his life in a communist regime, St. John Paul knew well Marxist ideas, which enabled him to deal effectively with the liberation theologians in South America.

I think of Kengor as plunging a stake into the heart of the devil and Karl Marx. But as we know, vampires are not so easily killed. Marxism in the 20th century used class warfare, and that was mostly a failure. In the 21st century, Marxists are employing identity politics, lately with some success. But the aim is the same: to sow cultural destruction. If this doesn’t make you angry, you’re not breathing.

Bizarrely romantic revolutions – from Mao’s China to Seattle’s Capitol Hill Organized Protest zone – Marx’s ill-conceived utopias aren’t just destructive, they’re murderous. The death toll of communism worldwide exceeds 100-million! Kengor calls it “nothing short of diabolical – truly a satanic scourge, a killing machine.”

Without question, America has had its share of betrayals and unrealized ideals, but what other country has made such progress with the rule of law, individual freedom, and shared prosperity?

Marx believed religion was a drug (the opium of the people) used by the wealthy to maintain disproportionate power. In retrospect, of course, communism peddles its own drug: an idealized global world, in which inequality disappears in the obliteration of all human distinctions. Kengor sees the seeds of our current flirtation with Marxism in the promotion of sexual freedom, “that plagues us to this today.”

Scripture teaches that, after the Resurrection, Lucifer was left only with the power to accuse, with rhetoric his only weapon. This is why Satan and Marxists prey on the most vulnerable: those least sure of their own identity. Satan comes as “an angel of light” (2 Corinthians 11:1), but he and his disciples, Marxist groups such as Antifa and the founders of the Black Lives Matter organization, bring only darkness.

Paul Kengor shows us the light.

COLUMN BY

Robert Orlando

Robert Orlando is a filmmaker, author, and entrepreneur. He’s the founder Nexus Media, and his latest films include The Divine Plan, and Citizen Trump. He also has a new book, The Tragedy of Patton: A Soldier’s Date with Destiny, forthcoming in November. His work has been published in HuffPost, Patheos, Newsmax, and Daily Caller. As a scholar, he specializes in biography, religion, and military history.

EDITORS NOTE: This The Catholic Thing column is republished with permission. © 2020 The Catholic Thing. All rights reserved. For reprint rights, write to: info@frinstitute.org. The Catholic Thing is a forum for intelligent Catholic commentary. Opinions expressed by writers are solely their own.