Who Do Economic Profits Belong To? by Sandy Ikeda

Do we deserve to keep the profits that result from our actions?

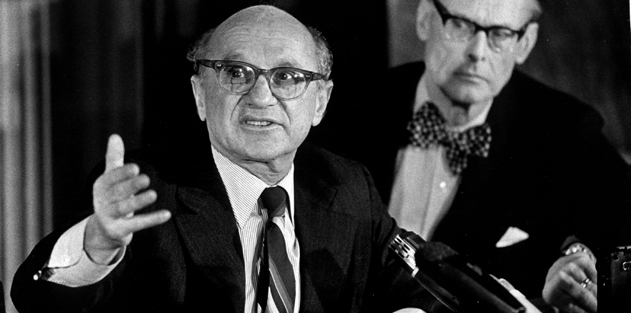

Most libertarians would maintain that any economic profit — the residual of revenue over cost — that you earn from voluntary exchange is indeed moral and rightly belongs to you. The puzzling thing is that standard microeconomic theory, which libertarians as well-known as Milton Friedman have used to defend their free-market beliefs, is completely irrelevant in justifying that belief.

I attended a talk recently given by Professor Israel Kirzner in which he addressed the question of whether economics can tell us who does and doesn’t deserve profit. I won’t summarize the entire lecture here, which I expect Professor Kirzner intends to publish, but I will touch on an important and often-neglected point he made.

Specifically, it’s that because microeconomic theory is utterly useless in morally justifying economic profit, we need to look beyond one of the most cherished slogans of economics: There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch, or TANSTAAFL for short. Indeed, in order even to begin seeing economic profit as moral, you have to set TANSTAAFL aside. (I wrote on a related theme in “But There ARE Free Lunches!” in May 2011.) Now, how does that relate to the question of who, if anyone, deserves economic profit?

The Value of the Marginal Product

Let’s say you want to sell a new kind of musical instrument. You buy or hire every single ingredient you need to produce it: the various kinds of skilled labor and equipment, the working space, management and financial knowhow, and whatever computing and power needs you require. You also contribute to production as the owner of the firm, and your contribution includes the risk you take to start the business as well as your industriousness, tenacity, and courage.

You then pay each and every one of these factor owners, including yourself, its “marginal value product,” which is the revenue the business earns from selling what each input produces. You pay wages or rents to everyone and a return to yourself to compensate for the resources you bring. Economists since John Bates Clark have used the marginal value product and continue to do so to explain how income from production is distributed. But there’s a problem.

Suppose, after paying all the input owners including yourself, there’s still something left over. That something, the residual of all actual revenue over all actual costs, is economic profit.

Again, you’ve paid every factor owner all of what each has contributed to the value of the musical instruments produced. That means that the value of the marginal product, the central concept in the modern microeconomic theory of income distribution, cannot explain who deserves to keep the economic profit because it cannot explain profit.

It’s important to keep in mind that economic profit is not “earned” in the same sense that wages and rents are earned. It is what’s left over after all other earned income has been paid out according to the value of its marginal product.

To whom then does economic profit properly belong?

The Concept of Entrepreneurship Offers a Clue

For Kirzner and other economists working in the tradition of Austrian economics, the key to answering that question, though not the complete answer, begins with the concept of discovery.

There is knowledge that we don’t possess because we choose not to know it. If someone asked me for the phone number of a person whose name is drawn randomly out of the New York City telephone directory, the chances are very good that I won’t know it. Although I’m aware of the existence of the directory, I haven’t memorized it, simply because I haven’t deemed it worthwhile. I’ve chosen not to know.

But if I didn’t even know of the existence of such a directory and I needed to call a particular person, my learning about the directory would come as a revelation. Moreover, I would have found out that I didn’t even know what I didn’t know — what Professor Kirzner calls “sheer ignorance.” He then defines entrepreneurship as that aspect of human action that discovers, and thereby removes, sheer ignorance.

What does the discovery of sheer ignorance result in? Economic profit!

Why marshal all the resources to produce a new musical instrument? Because you believe you see what no one else sees. You believe that it offers a better investment for you than what you’re doing now. Why do you think that? Because you’ve realized — made the discovery — that after compensating all the factors of production with the value of their marginal product, there will still be a pure residual left over that you couldn’t have gotten doing anything else. If you’re right, you get that residual, the economic profit; if you’re wrong, you suffer the economic loss.

This means, of course, that TAANSTAFL is wrong. Opportunities to make economic profit do exist. There are free lunches. In fact, in a world of sheer ignorance, such as ours, free lunches are everywhere.

Toward an Answer

I haven’t mentioned how Professor Kirzner addresses the issue of whether economic profit is moral or deserved. To get a good sense of what he says in the remainder of that lecture, have a look at his 1989 book, Discovery, Capitalism, and Distributive Justice.

(Also, see this book review by FEE writer Charles W. Baird.)

A good economist needs to have a firm grasp on standard microeconomic theory: supply-and-demand analysis and all that. At the same time, it’s important for her to appreciate its limits, which are severe indeed on the question of the morality, or even the origin, of economic profit.

Sandy Ikeda is a professor of economics at Purchase College, SUNY, and the author of The Dynamics of the Mixed Economy: Toward a Theory of Interventionism. He is a member of the FEE Faculty Network.