Hip Hop: A Free-Market History by Brandon Maxwell

Hip hop is not just music. It’s a culture. It includes dance, apparel, perfumes, jewelry, cinema, radio, television, books, magazines, and even beverages. That is, there are very few trades that hip hop hasn’t touched. And while hip hop’s lifeblood may be the complex grouping of rhythms, beats, vocals, tones, and lyrics, it was abetted at every stage by the free market.

Twenty-four million people around the world listen to hip hop each day. A half-million people see hip hop live in concert each month. And 28 million people purchase hip hop in stores each year. It is a $10 billion industry and growing. And yet its story resembles one familiar to Freeman readers: Leonard Read’s description of the vast complexity that goes into making a simple pencil.

Pass the Mic

Hip hop did not become a commercial and cultural powerhouse overnight. The free market acted as a catalyst. The market’s processes—competition, refinement, and augmentation—shaped the genre and the culture over time. They complemented the recording, mixing, and mastering process and aided hip hop in discovering new listeners. And, as is the way of the market, it helped listeners discover hip hop.

Hip hop’s free market venture first began 35 years ago in the northernmost borough of New York City with a handful of bored, mostly lower-income kids. They improvised lyrics over funk and soul music generated by DJs at block parties. As simple as it may seem to point out, none of this would have been possible without a variety of tools devised and made available through commercial means.

As spoken-word artists matured, New York City witnessed the advent of “emcees” (noun) bidding to “emcee” (verb) over personalized beats. With this development emcees needed additional tools, like samplers, synthesizers, and drum machines accompanied by tape players and record needles. “Rap” as a subgenre was born.

Likewise, emcees began to compete with each other. They contended not just for esteem, but for listeners in and around the neighborhood and city. This early competition elevated certain performers and improved the product overall, eventually allowing a select few to become famous. Throughout this process, as they competed with each other, emcees and DJs had to keep their customers satisfied. The audience could refuse to show up, walk out, heckle, or maybe even come up onstage and perform better themselves.

And consider the bedrock of hip hop: the beat. Going through old records—some forgotten, others much-beloved—artists found beats and breakdowns, extracted them, and turned them into the basis for an entirely new industry. To put it another way: They made gasoline out of oil refinery “waste.” And they made it possible for one person, or a handful, to put together music that would have required an expensive array of musicians just a few years before—and might not have been conceivable without the availability of new instruments like samplers and drum machines.

More Tools, More People

But these were far from the only tools hip hop purveyors and enthusiasts would need. On the contrary, hip hoppers would still have to have millions more tools, arbitrageurs, and entrepreneurs to carry them on their journey from block party boredom to billboard dominance. The process involved the collaboration of millions of people around the world and across time, very few of whom had any idea that they were, in fact, involved in the same endeavor—and no single one of whom could have created this force on his own.

Consider the millions of television sets and radios and the hundreds of radio stations it took to propel hip hop beyond its Bronx origins. Ponder the millions of power lines and hundreds of radio waves it took to transmit hip hop to those television sets and radios. And contemplate the number of television and radio station employees it took to ensure everything was transmitted properly. All of this is to say nothing of the level of productivity necessary to give millions of people both leisure time and disposable income to use on filling that time.

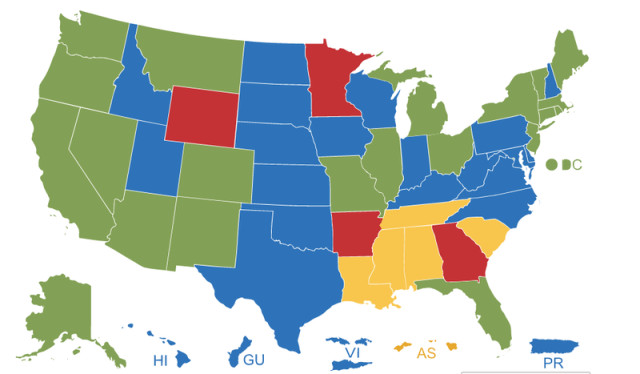

East Coast, West Coast, Dirty South

As hip hop spread across the United States, new emcees emerged, each meticulously tailoring variations on the music for a different audience. The result of these subtle adaptations was that hip hop gave rise to diverse qualities and styles, with each style suiting a different demographic or geographic location. That is, while hip hop could be heard in different cities across The United States, its sound in New York City, which found inspiration in energetic artists such as James Brown, did not often mirror its sound in Los Angeles, which found inspiration in the laid back funky basslines of Zapp and Roger. Its sound in Los Angeles was considerably different from the sound that emerged in the Deep South, which experimented outside of the usual 4/4 time signature. And its sound in the Deep South could be contrasted with the Midwest sound, which used faster tempos.

But in order for each different geographic location and demographic to continue to access hip hop over the decades, yet more tools were required. These tools consisted of millions of record players, tape players, CD players, mp3 players, and computers—not to mention millions of pairs of headphones, ear buds, and ¼-inch jacks, each meticulously designed to be used in conjunction with one another. It would require thousands of retailers across the world to transport and carry these accouterments. Thousands of companies would have to promote, advertise, and vend records, tapes, CDs, and mp3s. And as each new innovation appeared, it opened up new creative possibilities for entrepreneurs alert to the opportunity and for artists seeking new modes of self-expression. (And made it even easier for one person to play both entrepreneur and artist simultaneously.)

Production Value

Before arriving at this juncture, hip hop had to first achieve a polished and professional sound. This meant people had to design and build recording studios, which in turn meant the involvement of construction companies, masons, engineers, and architects. Construction workers use numerous power tools, thousands of nuts and bolts, hundreds of pounds of concrete, and dozens of beams for structural support—all of which had to be transported to a location. Once constructed, these recording studios would then be outfitted with mixing boards, microphones, monitors, preamps, limiters, compressors, and sound insulation—each item manufactured by a different company excelling in a distinct area of sound and recording (with components coming from all over the world).

In addition, a great number of people would be needed to assist in the actual recording process, with each individual wielding a select set of skills—e.g., producers and often separate engineers for sound, recording, mixing, and mastering.

And what about people who want to record from the comfort of their own homes? Can the free market help?

The evolution of the digital audio workstation (DAW) alone is a testament to the free market and Adam Smith’s division of labor. Dozens of individuals and companies have had to carefully work together in order to conceive a way to allow individuals the freedom to record from the comfort of their own homes.

The first precursor to Pro-Tools (the software most used in modern digital recording) was conceived in California by two college undergraduates. The result was a worldwide revolution in recording and an affordable way for millions of aspiring emcees to create quality music without commissioning the use of otherwise expensive mixing boards, effects processors, and analog tape machines.

Markets vs. Magistrates

Could hip hop as we know it today have been possible in a country devoid of a free market economy? Could any one man or government have rightfully determined and differentiated the kind of hip hop the West Coast wanted to hear from the kind of hip hop the East Coast wanted to hear? Could any one legislator or body of legislators have predicted the way hip hop would evolve—including the countless variations, textures, and styles? Could anyone have known beforehand that there was this unsatisfied—even undiscovered—hunger for a new kind of music, let alone offshoots in fashion and other industries?

Liberation

A free market does not inhibit, it liberates. A free market has no prejudices or preferences as to who benefits or who doesn’t. The market, rather, is a system that people animate with their creativity and service. The quality of the product rests solely on the shoulders of the entrepreneur—nobody else. And yet it is driven by communities.

The free market affords individuals and companies a platform to advance mutual interests. And in return, it offers consumers a variety of choices, options, and avenues, which sustainably advance yet more mutual interests.

It is because of these mutual interests that hip hop has become a household name. It’s even easier to access than water in some countries. And yet, it remains only one facet, one story, in an invisible agglomeration of individuals and businesses voluntarily collaborating across every hour of every day.

ABOUT BRANDON MAXWELL

Brandon Loran Maxwell is a freelance journalist, playwright, and regular contributor to Street Motivation Magazine, Los Angeles’s largest independent hip hop and urban publication.

EDITORS NOTE: The featured photo is courtesy of FEE and Shutterstock.