Money Will Be Digital — But Will It Be Free? by Andreas M. Antonopoulos

Bitcoin offers a glimpse into the future of money — a purely digital form of money that is individual, private, global, and free (free as in speech, not as in beer). Bitcoin is often compared with the existing banking system, juxtaposing its futuristic capabilities with the slow, antiquated, and cumbersome world of wire transfers, checks, “banking hours,” and restrictions.

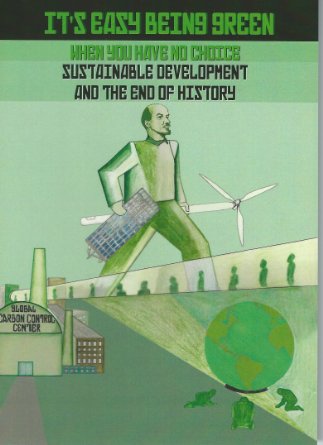

But the future will not be a choice between “old money” and cryptocurrency. Instead, it will be a choice between two competing visions of digital money: one based on freedom and choice, the other based on control and surveillance, a dystopian totalitarian system of control from which no one can escape.

We are now at the crossroads, and we must choose the future of currency wisely.

Cash, checks, and other forms of tangible money have been gradually disappearing for decades. We are now rapidly moving toward a cashless society where all money is purely digital. In the past, cash payments were expected and preferred; credit transactions were suspect. But as we turned into a debt-based society, cash became the oddity. The inscription “for all debts public and private” no longer rings as true. Today, if you try to buy a car with cash, you’ll be treated with extreme suspicion. Large amounts of cash are now associated with criminal activity and the definition of “large” is getting smaller each day. This is how we arrive at a cashless society: by making cash itself suspect, then criminal.

The transition from cash to digital money is not just a change in form. It is a transition from transactions that are private, person-to-person, and decentralized to transactions that are monitored, intermediated, and under centralized control. In the last two decades, digital payments have become a powerful surveillance tool. Citizens who are concerned about their government monitoring their telephone calls are simultaneously oblivious to the fact that every transaction they make with a plastic card or an online payment network can be scrutinized without suspicion of a crime, without warrants or any form of judicial oversight. Most national governments, under the guise of counterterrorism laws, have empowered their law enforcement and intelligence agencies with unfettered access to financial data. It shouldn’t surprise you to learn that these powers are used far more broadly every day, increasingly removed from the originally stated intent.

What a strange world we now live in. Total surveillance of every citizen’s transactions, without any basis or suspicion, is not just normal but presented as a virtue, a form of patriotism. Using cash or wishing to retain your financial privacy is inherently suspect, a radical position, soon to be a crime.

A future where all payments are trackable is terrifying, but a world with centralized control over transactions would be even worse. Digital currency with centralized control means the eradication of property as a right. Instead, your money exists only as a database entry where the balance is controlled entirely by a third party.

By managing the payment networks, a government has effective control over all participants, including banks, corporations, and individuals. Already, banks are extorted into adopting global financial blacklists for fear of being disconnected from networks like the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) and Automated Clearing House (ACH). This web of control is expanding and is used more and more frequently as a weapon of geopolitics.

The future of digital central currencies will make this control entirely individualized and easy to target. Attended the “wrong” protest? Your bank balance is now zero. Bought a suspicious book? Expect a visit from the police. Annoyed someone in power? They can trawl through your transactions until they find something juicy enough to leak.

Your movements can be tracked, your friends identified, your political affiliations analyzed and cross-correlated to your reading habits. No part of your life is private when every form of money is digital and every transaction can be tracked, blocked, seized, and deleted. Your life savings are yours only as long as you don’t offend someone in power. When money is centrally controlled, ownership of anything is a privilege the government can revoke. Property is not an inalienable right, but an advantage afforded to the those who acquiesce to the system. Combining surveillance of communications with complete control over money will result in tyranny the likes of which the world has never known.

Totalitarian surveillance of money is toxic to democratic institutions, and the power of surveillance erodes the social contract and corrupts those in power. There cannot be self-determination, freedom of expression, freedom of association, or freedom of conscience in a society where every penny you spend is monitored and controlled.

Even if you believe that your government is benevolent and will only use these extreme powers against “terrorists,” you will always live one election away from losing your freedoms. Even the supposedly benevolent governments in liberal democracies are already using their power over money to harass journalists and political opponents, while allowing their friendly bankers to finance tyrants, warlords, and militias across the world.

Bitcoin offers a fundamentally different future for currency. Bitcoin is digital cash; its transactions are person-to-person, private, and decentralized. It combines the best features of cash with the convenience, speed, and flexibility of a digital medium.

Bitcoin enables an alternative future of personal freedom and privacy that revokes the surveillance-state developments of the last few decades and reintroduces financial emancipation through the power of mathematics and cryptography. Through its decentralized global network, Bitcoin provides no central point to control, no position of power to enable censorship, no ability to seize or freeze funds through a third party without due process, no control over funds without access to keys.

Lacking a center of control, bitcoin resists centralization. Lacking concentration of power, it resists totalitarian domination. Lacking identifiers, bitcoin promotes privacy and makes total surveillance impossible. Disregarding political borders as network-irrelevant, it eschews nationalism and geopolitical games. Dispersing power, it empowers individuals.

Bitcoin is a protocol of free commerce, just as the Internet’s transmission control protocol/Internet protocol, or TCP/IP, is a protocol of free speech. Bitcoin’s design can be replicated to create myriad forms of decentralized money, all superior to the dystopian future we are otherwise headed for.

We can live in a world where money operates like any other medium on the Internet, free from control or interference. In a decentralized digital future, money will be controlled by individuals, banking will be an “app,” and governments will be as powerless to stop the flow of money as today they are powerless to stop the flow of truth.

In this future, money will be a tool of freedom from tyranny, an escape hatch from corrupt banks, a haven from hyperinflation. Four to six billion people without access to international financial services will be able to leapfrog the banking system and connect to the world economy directly. Individuals will not have to choose between directly controlling their own money and participating in a global financial network. They will enjoy global peer-to-peer finance, where trusted third parties and endless lines of bankers and intermediaries are things of the past.

While the future of currency is undoubtedly digital, it can take two radically different forms. We can live in a financial panopticon, a straitjacket of surveillance and tyranny. Or we can live in an open society where our privacy is protected by cryptography, not subject to the whim of every petty bureaucrat — where our digital money is global, borderless, anonymous, and controlled by the individual. The choice between financial freedom and financial tyranny is a choice between fundamental freedom and tyranny. Choose financial freedom: choose freedom.

Andreas M. Antonopoulos is a technologist and serial entrepreneur who advises companies on the use of technology and decentralized digital currencies such as bitcoin.

This feature film is narrated by Brian Sussman, San Francisco radio host (KSFO) and best-selling author of

This feature film is narrated by Brian Sussman, San Francisco radio host (KSFO) and best-selling author of